The Saskatchewan Election:

A 2020 Perspective

Organized Labour and the Impasse of Working Class Politics in the 2020 Saskatchewan Election

By Dr. CHARLES SMITH (PhD), Associate Professor, Department of Political Studies, University of Saskatchewan

Entering the 2020 Saskatchewan election, the labour movement understood that it was operating in a hostile political environment. Since the conservative Saskatchewan Party was first elected in 2007, the government has targeted the organized labour movement for its anti-conservative and pro-New Democratic Party (NDP) leanings. In government, the Saskatchewan Party has clamped down on workers’ rights to organize and strike, and has routinely restricted workers’ abilities to collectively bargain.[1] Partly because of these attacks and partly because of its long alliance with the NDP, the organized labour movement in Saskatchewan threw itself into the 2020 election campaign in order to build a working class base for a rebuilding NDP. Although that rebuilding assisted in training dozens of new activists and expanding its messaging to the broader working class, it did not translate into improved electoral support for the NDP.

The Lead up to the 2020 Campaign

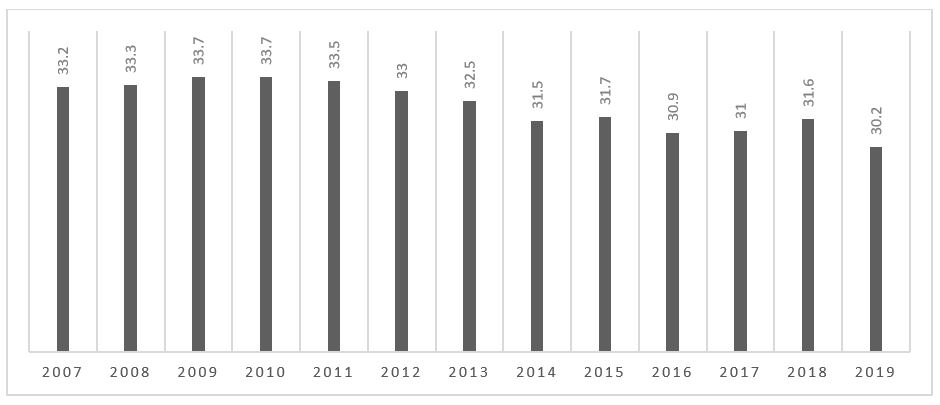

Under the leadership of Brad Wall and Scott Moe, the Saskatchewan Party has never prioritized a positive or even working relationship with the labour movement. Rather, the party has governed around the labour movement, speaking to workers about broad macro-economic issues rather than valuing the importance of worker representation through independent unions. On one level, this is surprising given that over 30 per cent of the provincial workforce belongs to a union (see chart 1). Yet, on another level, the Saskatchewan Party’s antagonistic relationship with unions reflects traditional right-wing hostility toward the organized working class. That hostility arises from the union movement’s close political connection to the NDP and, given the increasing concentration of unions in the broader public sector, in union abilities to challenge government directly through the withdrawal of labour.

It is for these reasons that under the Saskatchewan Party’s tenure, the Trade Union Act has been amended several times (and amalgamated into an Employment Act in 2014), generally with the goal of weakening labour’s collective power. The success of the Saskatchewan Party’s agenda is clear in at least two areas: first, since 2007, the unionization rate across the province has declined, notwithstanding a fairly significant economic boom in this period. Second, workers across the public sector have seen their negotiations delayed for months and even years, which has accelerated since the government mandated a public sector wage reduction in 2017. This latter issue was highlighted quite dramatically just prior to the election when frustrated long-term care workers represented by the Service International Employees Union West occupied the cabinet office in Saskatoon protesting the fact that they have been without a collective agreement for over three years.[2]

Chart 1: Unionization in Saskatchewan, 2007-2019[3]

The 2020 Election Campaign

Recognizing the long and antagonistic history with the Saskatchewan Party, the province’s labour movement entered the 2020 campaign with a goal of working with its allies in the NDP to build a broader electoral base of support for the party. That strategy was built on several principles. First, led by the Saskatchewan Federation of Labour (SFL), unions pushed several issues that were tied directly or indirectly to many of the policy priorities championed by the left and the NDP. These policies included prioritizing the creation of good union jobs and protecting the province’s treasured Crown corporations. Recognizing the detrimental implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on workers, the SFL also championed paid sick days for all workers, strengthened health and safety laws, expanded access of personal protective equipment for frontline workers, and ensured higher wages for “frontline heroes, and all workers.”[4]

More concretely, the SFL’s campaign of “Putting Workers First” closely mirrored the provincial NDP’s campaign platform of “Putting People First.” Many of the promises that the NDP raised in their platform—including a $15 minimum wage, restoring workers’ rights to join unions, enacting pay equity legislation, and expanding worker training—aligned with and was supported by the SFL campaign.[5] Importantly, these policy priorities were targeted at a large and non-unionized workforce, which was meant to appeal to a cross-section of the working class rather than just existing union members.

At the heart of the SFL’s campaign was associating the Saskatchewan Party’s economic message about “strength” in the economy with the fact that economic growth has led to a bleak future for thousands of workers who continue to struggle. In other words, the SFL’s herculean task was to counter the Saskatchewan Party’s corporate-funded messaging with the reality that hard-fought union wages and good jobs were increasingly a thing of the past. For the SFL, the election of an NDP government would not just bring better wages, greater economic security, and better-quality public services to all members of the working class; it would also assist in rebuilding a declining labour movement. In order to promote this message, the SFL sent dozens of activists into the field, while also promoting online campaigns and sponsoring public messages through advertising, in commercial print, and on social media sites.

Did the Message Resonate?

Judging by the results of the election alone, it is clear that labour’s immediate campaign goal was not successful. After all, the NDP resonated with less than 30 per cent of the electorate. Yet, the message and issues raised by organized labour’s “Workers First” campaign will not so easily be defeated. Those policies are clearly designed to organize the broader working class, which will be necessary as the province enters an uncertain economic future. While the SFL’s political goals fell short, its message will resonate well into the future.

References

[1] See Charles W. Smith, “Active Incrementalism and the Politics of Austerity in the “New Saskatchewan,” in Bryan Evans and Carlo Fanelli eds., The Public Sector in an Age of Austerity: Perspectives from Canada’s Provinces and Territories (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2018), 71-100. See also, Andrew Stevens and Charles W. Smith, “The Erosion of Workers’ Rights in Saskatchewan: The Saskatchewan Party, Labour Law Reform, and Organized Labour, 2007-2020,” in Patricia Elliot and JoAnn Jaffe eds., Divided Province: Wedge Issues and the Politics of Polarization in Saskatchewan (Halifax: Fernwood, 2021), forthcoming.

[2] “Union protesters conduct sit-in at government cabinet office in Saskatoon,” Saskatoon Star Phoenix, 21 September.

[3] Statistics Canada, Table 14100129, Union status by geography, annually, Saskatchewan [47]; Unionization rate (Percentage); both sexes; 15 years and over.

[4] Saskatchewan Federation of Labour, Putting Workers First, Who We Are, What We Stand For, http://www.puttingworkersfirst.ca/about

[5] Saskatchewan New Democrats, People First: Platform 2020, 10-11.