Pipeline Policy, Politics and the Public Interest

The dispute between the governments of Alberta, British Columbia and Canada over the proposed Trans-Mountain pipeline presents a compelling case study on a fundamental challenge that faces all governments, namely how to reconcile policy and politics. The reality is that good policy must also be sustainable politically.

By Dale Eisler, Senior Policy Fellow, Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public PolicyA Fundamental Challenge

The dispute between the governments of Alberta, British Columbia and Canada over the proposed Trans-Mountain pipeline presents a compelling case study on a fundamental challenge that faces all governments, namely how to reconcile policy and politics. The reality is that good policy must also be sustainable politically.

Admittedly that might seem counter intuitive. Why wouldn’t policy with positive outcomes greater than the negative also be popular? In an ideal world, it would. But that’s not the world we live in, and you often can’t assume broad agreement on the desired outcomes and its effects. With any policy there is the clash of vested interests and perceived winners and losers. If those opposed are strident enough, they can make the policy not worth the political trouble it creates. The result is that the policy agenda and the tools used to implement it are a reflection of the social, economic and cultural factors at play.

Such is the dilemma the federal government is trying to resolve with legislation that would put in place a regulatory regime for major resource projects, such as the Trans-Mountain pipeline. The full title of Bill C-69 is “An Act to enact the Impact Assessment Act and the Canadian Energy Regulator Act, to amend the Navigation Protection Act and to make consequential amendments to other Acts.” Its short title could be “Reform of the Environment Assessment Regime.” Some might prefer a more cynical description, such as “Reversing What the Harper Government Did Act.”

The objective is to implement a process that designs policy that meets the political imperative of public acceptability. In a very real way, the issue strikes at the heart of Canada, federalism and the resource-based economy that underpins the nation’s economy and, in many ways, its identity. As Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is fond of saying, a growing economy and environmental protection are linked. “Being strong on the environment and strong on the economy go together,” Trudeau told a Calgary audience. He then added the politics part of the equation by saying the previous Harper government “refused to do anything” sufficient to protect the environment. The inevitable result was that pipelines weren’t built because of a failure to realize the mantra that the economy and environment go together.1 To rectify the situation, the federal government has produced a sweeping and far-reaching 287-page piece of legislation that it hopes will produce sustainable policy and politics. No one should get their hopes up.

The policy challenge is multi-dimensional. In effect, the government seeks to bridge the divide between B.C. and Alberta, climate change and an oil economy, and often conflicting and deeply entrenched Indigenous and community interests. It seeks to do all that through a process that leads to a sustainable public consensus behind a specific policy outcome. More to the point, the purpose of the legislation is to achieve what some call “social licence.” It provides for exhaustive public engagement and consultation with all the right constituencies, takes into account the full range of environmental implications, allows for review and intervention at various stages of the political decision-making process, and, after all that, has an escape hatch in case the process recommends an outcome not worth the political risk. The assumption underlying the legislation is if you’re willing to engage, accommodate and consider all the factors, there will be a meeting of the minds. The economy will thrive and the environment properly protected. At least that’s the theory.

Environment and Climate Change minister Catherine McKenna puts it this way: “With better rules for major projects, our environment will be cleaner and our economy stronger. Making decisions based on robust science, evidence and Indigenous traditional knowledge, respecting Indigenous rights, and ensuring more timely and predictable project reviews will attract investment and development that creates good, middle-class jobs for Canadians.”2 If this sounds vaguely familiar, it should. In 2012, when the Harper government introduced its Responsible Resource Development (RRD) legislation, then NRCan Minister Joe Oliver said the plan was: “To increase environmental protection … to deepen consultation with aboriginals, and … to make this system—which is old, dated, duplicative, inefficient—more modern.”3

Erasing the Past

In effect, the new legislation seeks to erase the Harper government’s RRD legacy. In reality it doesn’t eliminate it, so much as embrace and re-label some of its policies, while broadening the scope of the regulatory process to include many other stakeholders, interest groups and factors.

The Harper-era reform was based on four concepts: more predictable and timely reviews; reduce duplication and regulatory burden; strengthen environmental protection; and, enhance consultations with Aboriginal peoples.4 The argument was that in the coming decade more than $500 billion in natural resource projects were in various planning stages. If Canada’s natural resources—in particular oil—were to successfully escape being stranded in North America and reach a more lucrative global market, there needed to be greater clarity and certainty to the review process. Without it Canada couldn’t realize world prices for its oil and would be unable to attract the necessary investment. With no legislated time limits, reviews could, and often did, go on for years, with as many as 40 federal departments and agencies part of the process.

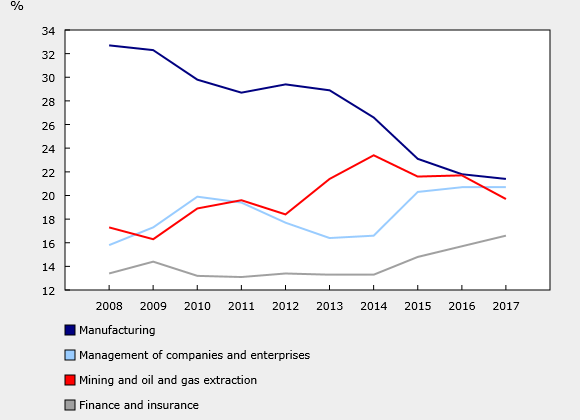

The same holds true today. It’s worth noting that much of the rationale around the Trudeau government’s legislation mirrors that of the Harper government. Even the language sounds familiar. In its justification for its legislation, the Government talks about the economic imperative of “hundreds of major resource projects, worth over $500 billion in planned investment.” It talks about the need for “clear timelines”, and “more coordination with the provinces to reduce red tape and duplication.”5 The message is that international investors are abandoning Canada’s oil and gas sector because of the regulatory uncertainty and our inability to get infrastructure built. According to Statistics Canada, in 2017 the stock of investment in oil and gas extraction fell by 7.4 per cent to $162.2 billion, as foreign direct investors sold some of their assets back to Canadian investors.6

In the words of the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP), investment in the Canadian oil and gas sector is drying up. It notes capital spending in the sector in 2017 was down 46 per cent from 2014. How much of that relates to a loss of investor confidence because of the project review process, as opposed to the precipitous decline in oil prices that hit in 2014 is a good question. But CAPP does point out that last year capital spending on oil and gas in the U.S. grew by 38 per cent, to equal the same level that has taken Canada 150 years to reach. The causes it cites are increasing government costs, inefficient regulation and the lack of infrastructure.7

The system proposed by the Trudeau government creates an Impact Assessment Agency and a Canadian Energy Regulator, which effectively is a rebranding of the current Canadian Environment Assessment Agency and the National Energy Board. The process will have five stages: Early Planning; Impact Statement; Impact Assessment; Decision-Making; and Follow-up, Monitoring and Enforcement. The government argues the proposed system will result in a more efficient, transparent and predictable process. It in fact shortens the review timelines imposed by the Harper government legislation. The key objective is to secure so-called social licence by expanding public participation and the factors taken into consideration. Essentially the government intends to use process to overcome conflicting views and build the consensus necessary for projects that meet the public test to go forward. In other words, find the formula for good policy and successful politics.

The preamble to the legislation sets out the government’s intent to embrace a wider spectrum of views. It talks about “achieving reconciliation with First Nations, the Metis and the Inuit” through renewed nation-to-nation, government-to-government relationships. It references use of the “best available scientific information and data and the traditional knowledge of the Indigenous peoples of Canada are taken into account in decisionmaking.” It also talks about being committed to “assessing how groups of women, men and gender-diverse people may experience policies, programs and projects.”

To do that, the legislation significantly broadens the factors that must be taken into account as part of the impact assessment. A non-exhaustive list includes:

- cumulative effects likely to result in combination with other physical activities;

- impact it may have on any Indigenous group or the rights of Indigenous people;

- traditional knowledge related to the project by Indigenous people;

- the extent effects “hinder or contribute” to meeting the Government’s commitments regarding climate change;

- considerations related to Indigenous culture;

- community knowledge provided regarding the project; and,

- the intersection of sex and gender “with other identity factors.”

By casting a wide net that captures an extensive range of interests, the government believes it will have a process that meets the test of credibility, inclusiveness and transparency that legitimates its ultimate decision. It is an approach, some will argue, that is either naive or a public relations exercise. It’s not about fixing a flawed process that will defuse emotions, but irredeemably opposed interests and opinions. There is no middle ground to cultivate. The issue is not a specific pipeline or project, but whether to continue expanding oil production, or reduce and eventually eliminate it as much as possible. From B.C.’s perspective, it’s about the potential of a massive oil tanker spill of diluted bitumen in Vancouver’s Burrard Inlet or along its coast, and its authority to deal with that threat.

There should be little doubt the proposed process will more thoroughly weigh the environmental risks. But, if as the Prime Minister says, the environment and economy need to be considered together, the new process fails. It doesn’t attempt to weigh the economic risks and consequences on Canada of a project not proceeding.

Political Will

Any decision comes down to the political will to act. Without it, policy is stalled. In terms of the Trans-Mountain project, the Prime Minister has said that the pipeline from Edmonton, along an existing pipeline right-of-way to Burnaby, is in the national interest. The project has already gone through a 29-month regulatory process and been approved by both the National Energy Board and the federal government, contingent on 157 conditions being met. In the wake of threats by Kinder Morgan, the proponent, to withdraw from the project due to ongoing uncertainty over its status, Trudeau has signalled the federal government could consider a financial backstop to ensure the pipeline is built.8

Ironically, the fate of Trans-Mountain is unconnected to the proposed new review process, as the new legislation proposed by the federal government relates only to future projects. The jurisdiction over inter-provincial pipelines is well established by the courts and is explicitly the responsibility of the federal government. So while the B.C. government can attempt to bog the project down in the courts or in the process to issue provincial and municipal construction and environmental permits, it has no apparent constitutional authority to stop the pipeline. There will undoubtedly be ongoing demonstrations by those opposed to the pipeline, including Indigenous people asserting their rights. But if it is deemed in the national interest, as the Prime Minister has stated, then it will be the responsibility of the federal government to ensure the national interest is protected. Inevitably questions loom: How strong is the PM’s political will? How far will the federal government go in pursuit of the national interest? How far will opponents go, whether the B.C. government or other interest groups, to oppose the project?

Going forward, the core issue is whether the new regulatory review process proposed by the Trudeau government will meet the test of providing the public legitimacy necessary for sustainable policy it seeks. Experience in recent years has demonstrated that getting regulatory approval for a project is no longer sufficient for it to move forward in the face of opposition of those who say the process is flawed. The Northern Gateway pipeline project went through a punishing review, was approved with more than 200 conditions, but ultimately died at the political level when the court ruled there had been insufficient consultations with First Nations. The Energy East project, which many deemed in the national interest, also collapsed because of public opposition, often at the local level, particularly in Quebec.

The new regulatory process clearly attempts to better engage the competing interests and opinions that converge around resource projects. Inherent in the logic is the belief that consultation and inclusion of more factors and interests will lead to consensus. In effect that process will produce good policy. But the regulatory process is not the place where policy issues can be determined. First comes leadership that establishes a policy.

The regulatory process is the means to determine the best implementation to achieve the policy end. The regulatory process should not be the forum for dealing with competing environmental, social, Indigenous, cultural and economic interests. It is not equipped, nor should it be expected, to resolve those differences. It is where experts make recommendations on the best way forward in addressing the technical, scientific and environmental issues surrounding the project. It should not be a focus group that somehow adjudicates what are essentially political considerations. Imagine a regulatory review that needs to consider and incorporate the complexities of Indigenous rights, upstream and downstream climate change effects, the blending of Indigenous knowledge with scientific data and facts, and determining the impact of the proposed project on sex, gender and other identity factors. It risks turning into an even more unmanageable process that inevitably leads to stalemate.

Determining National Interest

Ultimately, the critical decision factor must be national interest. At the end of the day, national or public interest is in part an abstract and subjective concept that needs to be determined at the political level. It goes well beyond just the sum of measurable benefits and risks to include consideration of the impacts on individuals, groups and the nation itself as an entity. In the case of Trans-Mountain, which exposes the political, economic, Indigenous, cultural, environmental and regional divisions, there must be the capacity for the federal government to rise above local, regional and specific group interests to judge what it considers to be the interests of the nation.

The expanded regulatory process will undoubtedly give a greater voice to all those who oppose or support a specific project that has significant environmental and economic implications. But in so doing, it will also put greater focus on what divides people. No one should think it will resolve what often are irreconcilable differences and create agreement on the way forward where none exists.

In the end, process won’t lessen the policy dilemma, but it will better frame the political decision for the Government of Canada on what is, or isn’t, in the national interest. Ironically, former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, father of the current PM, perhaps expressed it best. When dealing with disputes involving the provinces and the federal government, often over energy issues, he used to ask rhetorically: “Who speaks for Canada?” Who, indeed.

Works Cited

2 https://www.thelawyersdaily.ca/articles/5872

3 http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/resource-development-a-rockyroad-for-feds-1.1217927

4 p. 92, Economic Action Plan, 2012, Government of Canada

5 Better Rules for Major Project Reviews, A Handbook, ECCC, Government of Canada

6 http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/180425/dq180425aeng.htm

ISSN 2369-0224 (Print) ISSN 2369-0232 (Online)

Dale Eisler

Prior to joining the JSGS, Dale Eisler spent 16 years with the Government of Canada in a series of senior positions, including as Assistant Deputy Minister Natural Resources Canada; Consul General for Canada in Denver, Colorado; Assistant Secretary to Cabinet at the Privy Council Office in Ottawa; and, Assistant Deputy Minister with the Department of Finance. In 2013, he received the Government of Canada’s Joan Atkinson Award for Public Service Excellence. Prior to joining the federal government, Dale spent 25 years as a journalist. He holds a degree in political science from the University of Saskatchewan, Regina Campus and an MA in political studies from Vermont College. He also studied as a Southam Fellow at the University of Toronto, and is the author of three books.