Unintended Consequences: Saskatchewan Assured Income for Disability

Saskatchewan Assured Income for Disability (SAID) was intended as an income support program for people with severe and prolonged disabilities. It has already expanded well beyond this target group, and continues to spread as time passes.

By Rick AugustSaskatchewan Assured Income for Disability (SAID) was intended as an income support program for people with severe and prolonged disabilities. It has already expanded well beyond this target group, and continues to spread as time passes.

After years of decline, dependency is now rising again in Saskatchewan, primarily because of SAID. If the experience of other jurisdictions holds true, this upward trend in dependency will continue unless a policy change intervenes.

The short-term result is a larger, more costly and more confining welfare system, but it may also signal a basic change in the dynamics of welfare dependency in Saskatchewan.1

This brief examines problems in the SAID program model, and outlines principles for a more effective and inclusive Saskatchewan disability policy.

Understanding Disability

Good disability policy requires accurate understanding of the concept of disability, in at least two important respects.

First, disability is not binary. People are not either disabled or non-disabled. Human beings vary in their capacities and potential, regardless of disability, and virtually every individual has some disabling element in his or her life, ranging from minor to severe. Disability is a continuum, not a discrete state.

Second, disability and employability are two separate issues. We know there are people who are too disabled to work but, apart from a small group of profoundly disabled individuals, we can’t accurately predict in advance who they are.

Some individuals with severe disabilities make their way very well in the world, others less so. Personal characteristics, treatment processes, motivations and other individual factors interact with community accommodation and the policy environment to affect outcomes.

SAID is misaligned with both of these concepts. It treats disability as a binary or discrete state. Applicants are required to prove incapacity at an essentially arbitrary threshold to be considered “disabled”.

Once they do so, they are exempted from work expectations and placed within a benefit structure that carries with it, as we shall see, the most extreme of work disincentives. To qualify for SAID is to be consigned, in effect, to the status of permanent unemployability.

SAID caseloads and costs

The SAID program was initially rolled out in 2009 to a population of 2,700 individuals living in institutions. A decision was announced in 2012 to expand SAID to independent living arrangements, with a new caseload target of 9,700.2

With just under 15,000 current cases, SAID has already over-run this target by about 50%. Is this too many? Evidence strongly suggests it is.

Legacy welfare included a ‘disabled’ category of cases that numbered at peak about 13,000. This was a very mixed group—an internal study estimated that about 40% had no significant functional impact from their disabling condition.3 This leaves about 8,000 legacy welfare cases, including an unknown number who were moderately but not severely disabled.

The government’s caseload target for SAID of 9,700 cases was therefore much higher than a reasonable estimate of severely disabled persons likely to need welfare support. The actual reach of the SAID program is already some 2,000 cases higher than previous dependency among people with mild, moderate or severe disabilities.

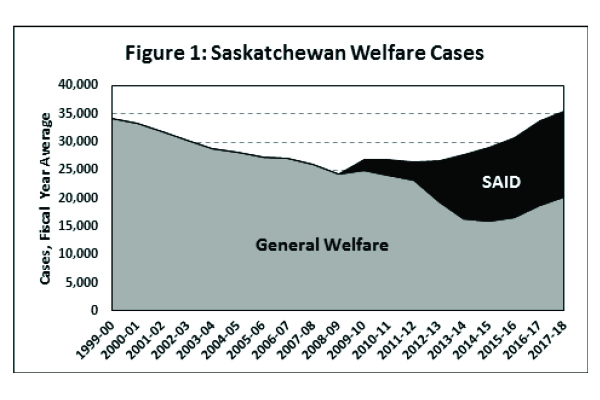

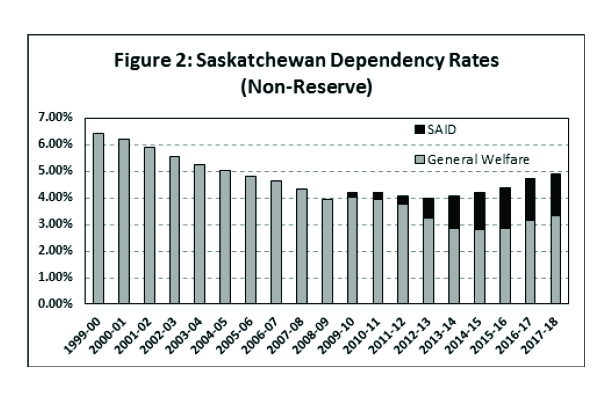

Figure 1 shows the proportions of SAID and general welfare cases in Saskatchewan. SAID now represents 43% of welfare cases, on a rising trend.

Figure 2 shows the trend in welfare dependency before and after SAID. It can be seen that most of the increase in recent years has come from SAID.

SAID’s impact on dependency is reflected in costs. The total welfare bill, pre-SAID, was $235 million. By last year it had risen to $446 million, a 90% increase in nominal dollars, and a 64% increase in constant dollars. The SAID program alone last year cost $224 million, equivalent to 95% of the entire welfare budget prior to the program’s introduction.4

Why is the SAID caseload increasing?

Messaging

Welfare is very sensitive to political context. SAID was treated as a showcase initiative under the slogan of making Saskatchewan “the best place in Canada to live for people with disabilities”.5 The message was that to be on SAID was a good thing.

Officials and ministers reinforced this view. The Ministry of Social Services Annual Report in 2012-13 called rising SAID caseloads an “achievement”, and the following year noted approvingly that “[g]reater than anticipated growth likely reflects the enrolment of new clients who were not previously recipients of any provincial assistance program.”6 The finance minister, in a recent statement, claimed higher welfare costs as an achievement of her government.7

Questionable design choices

A number of unusual design decisions were made in the development of SAID. An extensive list of resources can be ignored as income, including trust assets and trust income. This means that individuals who have been endowed, presumably by affluent parents, can continue to receive full public subsidy regardless of personal wealth. Major income sources like the Guaranteed Income Supplement are still ignored for most recipients.

Changes made in 2017 raise a different sort of concern. Presumably in response to caseload pressure, a decision was made to exclude new applicants from SAID who could qualify for any amount of Old Age Security (OAS), the basic federal pension. This effectively excludes all seniors from SAID, regardless of their income or disability status.8

Diagnosis-based eligibility

Medical diagnosis is an unreliable driver for disability programs. Diagnosis also shifts the power of qualification towards medical professionals who generally view themselves as accountable to the patient rather than to public policy. Physicians can be used to stretch the boundaries of benefit systems.9

This problem is avoidable if the benefit system focuses on functional impact rather than diagnosis. Efforts in this direction in the early design of SAID seem to have been abandoned in favour of a diagnosis-driven approach. Virtually all references to disability impact in the SAID regulations were expunged in 2016.

Advocacy

Disability advocacy aims to qualify more people, expanding the boundaries of a binary program like SAID. The result is a program that serves more and more people who are, on average, less and less disabled, at greater and greater cost to the public.

Advocacy pressure also makes governments reluctant to reform programs. Changes to SAID so far have been greeted with sharp criticism, which politicians are understandably reluctant to resist.

Work is less attractive

A single person’s net income from general welfare would be between $8,000 and $12,000 per year, equivalent to from 14 to 20 hours of work per week at minimum wage. The equivalent for SAID would be about $20,000 per year, equivalent to about 35 hours per week.

SAID appears to encourage a choice of welfare over work. This contrasts with the admirable roots of the SARCAN social enterprise, which aimed to take employment of people with disabilities closer to the mainstream economy.10

Looking at current SARCAN operations from the viewpoint of this consumer, it appears that SARCAN’s ‘real jobs’ approach is struggling to compete with SAID as a life choice for adults with disabilities.

Extreme work disincentives

SAID is relatively generous by welfare standards, but most adults would aspire to more than a peak of $15-20,000 annual income in their lifetime. Someone who qualifies for SAID, however, is not likely to do better, because earning money will rarely make economic sense.

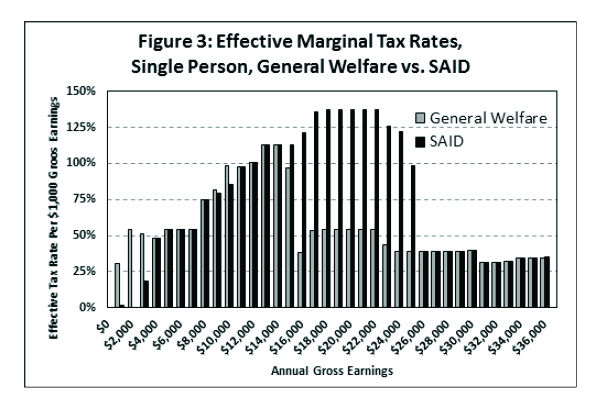

This is because a welfare program like SAID does not exist in isolation of other programs or the tax system. Figure 3 shows what happens to an individual’s effective marginal tax rate as he or she moves up the earnings range.

The y-axis in Figure 3 is the rate of taxation on each increment of $1,000 earnings. The gray bars are the general welfare recipient, the black bars SAID.11

The marginal tax rate challenge is hard enough for the general welfare recipient, with little or no net return on work below about $16,000 annual earnings. This is equivalent to around 28 hours of work at minimum wage.

The situation for the SAID recipient is much worse. Marginal tax rates are as high as 130% over a long range of earnings. Expressed in simple terms, a person in these income ranges, by earning $1,000 more in gross wages, would experience a net loss of $300 in disposable income. Unless that person can jump from no earnings to the equivalent of 40 hours per week at $12.50 per hour, work will not make economic sense.12

The future of dependency

SAID has created immediate problems for Saskatchewan. Costs are high and growing, welfare dependency is increasing, and SAID beneficiaries are caught in a classic welfare trap. SAID limits human potential and deprives communities of human resources. It also absorbs fiscal resources that could support a better disability policy.

The unplanned growth of SAID, however, points to a larger concern: a basic shift to a program model that effectively repackages economic dependency as disability.

SAID’s caseload growth should have been no surprise; caseload inflation has occurred in all such programs. In Holland, for example, disability benefits at one point consumed 3% of GDP. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) continues to strongly advise against passive disability benefit programs like SAID.13

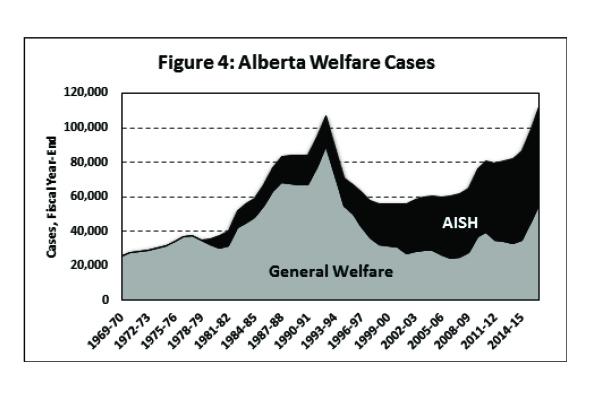

There is an instructional example, however, much closer to home: Alberta’s Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH) program, launched in 1979. Ten years into its existence, AISH had about 16,000 cases. In March 2017 it had 57,000 cases.

As Figure 4 shows, this program has changed the vector of dependency in Alberta. That province, some years ago, reduced its general welfare population through drastic reforms. With AISH now essentially its go-to welfare option, it seems that Alberta welfare dependency has not been tamed at all—has merely moved behind a screen of administratively-framed disability.

Saskatchewan appears to be headed in the same direction, transitioning from a program aimed at relieving economic distress to one driven by an ever-widening concept of disability. With an aging population and the force of internal and external pressures, we can expect the scope of SAID to continue to spread.

SAID will soon represent a majority of welfare cases in Saskatchewan. Paid at preferential rates, exempt from employment expectations and constrained by powerful work disincentives, disability beneficiaries will become a large, growing, and permanent dependent class, unless policy changes intervene.

What should governments do?

Disability policy needs to provide support, but it also must allow individuals to develop their potential to live more fully in the social and economic mainstream.

Following are some suggested principles for reform:

- The goal should not be more welfare, but the displacement of welfare by better alternatives.

- Welfare should be a single unified program that addresses only universal human needs of food, clothing and shelter, at the same rates for all beneficiaries.

- Non-universal needs like disability should be addressed outside of welfare, to reduce depth of dependency and encourage participation in work and community.14

- Disability supports should be based on functional impact of disability, not medical diagnosis.

- Disability supports should be individualized to the specific and variable needs of each person.

- Program targeting should be equitable with respect to both income and need level.15

- The focus of new disability resources should be on real community inclusion, real independence, and where possible, real jobs.

This, obviously, is a competing vision to SAID. Given the resources absorbed by SAID and the vested interests it creates, the path to reform will be difficult.

I would argue, however, that a better disability policy is possible, as long as we adhere to a consistent, positive and inclusive strategic vision.

Footnotes

ISSN 2369-0224 (PRINT) ISSN 2369-0232 (ONLINE)

Rick August

Rick August is an independent social policy analyst and consultant based in Regina. He is a former Saskatchewan public servant with over forty years of experience in the social policy field.

This is a condensed version of a self-published paper.

People who are passionate about public policy know that the Province of Saskatchewan has pioneered some of Canada’s major policy innovations. The two distinguished public servants after whom the school is named, Albert W. Johnson and Thomas K. Shoyama, used their practical and theoretical knowledge to challenge existing policies and practices, as well as to explore new policies and organizational forms. Earning the label, “the Greatest Generation,” they and their colleagues became part of a group of modernizers who saw government as a positive catalyst of change in post-war Canada. They created a legacy of achievement in public administration and professionalism in public service that remains a continuing inspiration for public servants in Saskatchewan and across the country. The Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy is proud to carry on the tradition by educating students interested in and devoted to advancing public value.