Competitiveness in a Protectionist World: Should We Send in the Diplomats?

Often governments get siloed in their thinking. They become so immersed in how they traditionally approach public policy issues that they fail to broaden their perspectives in search of new insights. This habit, which misses opportunities in a business-as-usual world, becomes a real risk in times of rapid change.

By Kevin Lynch, former Clerk of the Privy Council and Deputy Minister to the Prime MinisterOften governments get siloed in their thinking. They become so immersed in how they traditionally approach public policy issues that they fail to broaden their perspectives in search of new insights. This habit, which misses opportunities in a business-as-usual world, becomes a real risk in times of rapid change.

Competitiveness, the usual preserve of business leaders and economists, is a case in point. It is a subject that acts as a key driver of both innovation and economic growth. Today, the global context in which we compete is in significant flux—protectionism is on the rise, geopolitics has moved to a new plane, climate change is a planetary threat, and pandemics are a global reality. All represent global policy issues that will directly and indirectly impact Canadian competitiveness. It represents a new context, one where diplomacy and foreign policy have to become more a part of our competitiveness thinking and toolkit. That emerging intersection is what this Policy Brief will explore.

The challenge for Canada is rebuilding competitiveness in this rapidly transforming world, both geopolitically and technologically, in which the new protectionism is only part of the complexity. The nature of competitiveness itself is evolving as part of this transformation. With the digitalization of everything and the globalization of public health, data security and environmental threats, competitiveness now goes far beyond just commerce.How we compete, where we compete, how well we compete—all of these core competitiveness questions now need to be seen as integral to foreign policy development and execution in this changing global context.

A pretty basic and important question, for both a firm and an economy, is: how do we want to compete? While over-simplified, the choice is increasingly binary: do we want to compete in global markets by selling a commoditized product at the lowest price, or by selling a differentiated product at a premium price? The former is a race to the lowest price through scale and cost cutting, the later is a race to add value and distinctness through innovation and creativity. The drivers of this bifurcation have been predominantly globalization and technological change.

And not unrelated, the determinants of competitiveness have also evolved in response to globalization and the technology revolution. While there is no set list, most economists today would include government taxes and regulations; public debt; labour force quality; research capacity; innovation capability; public infrastructure; and market access. In the near future, they may add cyber-resiliency, pandemic preparedness and perhaps inequality.

To start, let’s review briefly the state of Canadian competitiveness, and do so through three separate lenses—the rankings perspective of the global indices of competitiveness, the trade balance perspective segmented by sector and market, and the business CEO’s perspective as they make investment and operational decisions.

Rankings Perspective on the Global Indices of Competitiveness

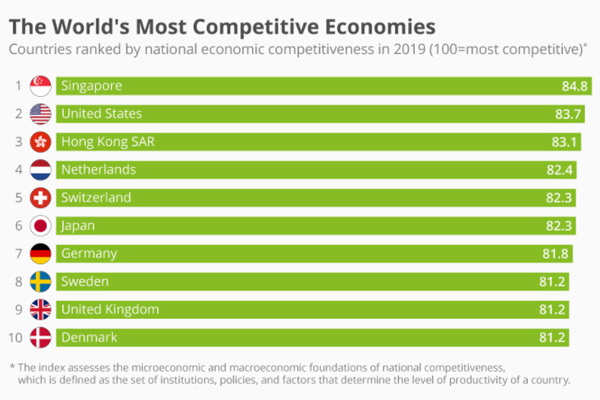

So, how does Canada rank on the first perspective of competitiveness, namely the international competitiveness indices? The best-known is the Global Competitiveness Index, compiled by the World Economic Forum and using an array of comparative determinants. Here, unlike a decade ago when Canada was in the top 10, we rank 14th—neither great nor terrible.

Figure 1: The World’s Most Competitive Economies

But what is most worrisome in this global ranking is that the competitiveness determinants where we most lag our competitors, are the core elements shaping future competitiveness: innovation capability, ICT adoption, infrastructure, and market scale. Innovation is a key driver of new products, processes and productivity—but Canada ranks 21st on the Bloomberg Innovation Index and much worse on OECD global indices of business adoption of new technologies and innovations. Infrastructure directly impacts firm level and national productivity, and our transportation and digital infrastructures have fallen behind many of our competitors. Access to global markets is essential to achieving scale for a mid-sized economy, particularly one that imposes internal trade barriers between provinces, and here protectionist threats and actions impact our competitiveness. Importantly, being a medium-sized economy is not the problem—smaller countries like the Netherlands, Switzerland, Sweden and Denmark consistently outperform Canada in international competitiveness rankings and in global markets.

The Trade Balance Perspective

A second viewpoint on our competitiveness is the trade balance—what we trade, where we trade, and the balance between what we sell and what we buy. Our main value-added exports are natural resources (oil and gas, agriculture, minerals, lumber and seafood), autos and auto parts. Our main export market is the United States, accounting for roughly 75% of our trade. And our overall trade balance is in a sustained deficit, made up of significant but declining surpluses with the United States, large and continuing deficits with China and mixed results with our other trading partners.

Many aspects of this sectoral and markets perspective on competitiveness are problematic, starting with oil and gas.

Energy has been our largest export to the United States for decades. In 2019, Canada was a net exporter of energy of $76 billion, an amount that fully covered Canadians net imports of consumer goods ($55B) and travel services ($11B). But the combination of the shale oil/gas revolution, constrained pipeline capacity, climate change measures and lower global energy prices has had a growing negative impact on the Canada-U.S. trade balance, which will undoubtedly continue in the future. This, in turn, has significantly reduced “resource rents” in an important sector of the Canadian economy, imperilling profits, high worker incomes and government revenues. Going forward, adjusting to climate change will force further structural changes to Canada’s oil and gas sector.

At the same time, the auto balance—a key element of our trade balance since the Auto Pact in the 1960s—has been negatively affected by structural shifts in assembly to Mexico, shifts in auto value added to software from hardware, and shifts in American demand towards European and Asian imports. And lastly, a major structural shift in trade volumes is underway, from goods to services, and within services, towards digital services.

There are two critical take-aways from this sectoral and market perspective on competitiveness: first, we need to rethink how we gain market share for our exports in the large American market, and second, somewhat paradoxically, we have to diversify our trade away from an excessive reliance on the U.S. market.

This was the logic behind the revised USMCA, the TPP11 and the Canada-EU trade agreement. But there is a danger that governments confuse trade agreements as ends in themselves rather than as the means to greater market penetration and exports. We simply have to take better advantage of these agreements. Equally, we have to be clearer on where we have comparative advantages or where we can accentuate an existing advantage. In our exports, value added agri-food to Asia would seem a good place to start. Whereas, clean tech— often cited as a golden export opportunity—lacks clarity on where our specific competitive advantages lie and in which markets.

The Business CEO’s Perspective

A third approach to competitiveness is a micro one. It is to benchmark the factors that matter most to the decision making of corporate CEOs, as they allocate capital, relative to their main competitors, particularly the United States.

Here, the biggest competitive concern is regulation not taxes, with a focus on increased complexity and greater uncertainty, particularly around environment approval processes. Our corporate tax advantage over the U.S., created in the early 2000s, disappeared with the Trump tax cuts, and is now a disadvantage unless Biden makes good on his election promise to raise them to essentially our levels. On the corporate front, Canadian business invests far less capital per worker and R&D per worker than American businesses, damaging our productivity, and as a result, business sector productivity levels in Canada are only 75% of those in the United States.

On the more positive side of the ledger, talent attractiveness is clearly an asset for Canadian competitiveness, especially during the Trump era and its H1 visa restrictions. But it will also diminish under the Biden Administration unless we do more on the immigration front. Low government debt-to-GDP, which has been a two-decade Canadian advantage, is rapidly disappearing with the massive rise in federal debt in response to the pandemic. Canada ranks poorly on public infrastructure, which hurts productivity, but here the U.S. is equally poor so neither country can be seen to have a competitiveness advantage. Canada’s research-intensive universities are world class, which is good, but there is only one in the global top 20 and only 5 in the top 100. Meanwhile, the U.S. and U.K. dominate the university rankings, with China on the rise.

The bottom line is that, in terms of our competitiveness, we are good but not great, and yet Canada’s standard of living is much more akin to that of a nation with top-tier competitiveness rather than average. The reason Canada has been able to maintain a high standard of living is because of borrowing—by both the public and private sectors. But that is not a sustainable long-term solution. We either have to improve our competitiveness or accept declines in our living standards.

Challenges for Canada

We began with the implicit question: what is the nexus between competitiveness, geopolitics and diplomacy, and how is it changing? With a highly inter-connected global economy, where the U.S.- China tensions and threats are the new geopolitical reality, and where innovation is the new fuel of growth, the convergence of populism, nationalism, security and tech competition will simultaneously challenge our competitiveness and our foreign policy.

There are six geopolitical issues that exemplify these inter-connected challenges for Canada. All will force us to make foreign policy choices which will affect our national competitiveness. None was confronting policy makers even as recently as a decade ago. Fiendishly inter-related, they are:

- U.S.-China tech cold war: We again have duelling super-powers. This time they both have massive economies and large militaries and share a common view that strategic technologies are the key to winning this cold war. The weapons of this battle for tech supremacy are the tools of trade policy—market access, tariffs, investment restrictions, capital market restrictions—and there will be collateral impacts on the advanced countries and their economies depending on how and where they align as new alliances form.

- Regulating data and the info-tech titans: The info-tech titans are modern day monopolists, and data is their currency. As governments push back on data privacy, content norms, taxation and standard setting, differing national objectives will likely give rise to regulatory fragmentation between the U.S., China, and perhaps the E.U. as well. The result will be the creation of “Splinternets” in the core global digital infrastructure, with the equivalent of digital Berlin Walls being constructed between China and the West.

- Buy America protectionism: U.S. protectionism, despite the USMCA, undermines the concept of rules-based trade, and will induce other countries to do the same. Buy America at the federal level encourages state and local governments to act similarly, and when extended to national security over-rides on supply contracts (think 3M masks during COVID) the result is to undermine both market access for Canadian exporters and supply chain access for Canadian producers and consumers. At a minimum, Canada should push for a Buy North America approach given the USMCA.

- Rethinking global supply chains: Global supply chains were the inevitable result of corporations in advanced economies seeking lower production costs through wide-spread out-sourcing, coupled with national industrial policies in developing countries, led by China, that were designed to achieve significantly lower costs through massive scale and cheap labour. It greatly benefited American consumers and corporations, but also fed the populist outcry to the hollowing out of middle-class jobs in the United States. The intersection of this populist storm with the widespread COVID-19 shortages in critical goods as supply chains sputtered during the pandemic has led to calls for re-shoring, near-shoring and diversification to build resiliency and security into the domestic supply chain system. National approaches to this rethinking may differ, but expect diversification of supply chains away from China to other Asian countries, as well as security considerations for certain goods to become paramount, resulting in the costs of consumer goods to rise.

- Reshaping of global institutions: As the U.S. and China joust for economic and political supremacy, other countries will be increasingly forced to choose how and where they align and on what issues. Whether it is leveling the playing field of trade rules with respect to China, the transparency and independence of bodies charged with pandemic preparedness and health intelligence sharing, the protocols for next generation internet, and the governance of the Bretton Woods institutions—the World Trade Organization, World Health Organization, International Telecommunication Union and International Monetary Fund/World Bank—will be front and center. These decisions will have commercial as well as geopolitical consequences.

- Climate change is a global threat in search of a global response: It is clear the design of national climate change policies will affect the competitiveness of sectors and entire economies. But so too will the extent and nature of international coordination. Will the COP multilateral climate change process lead to agreed and verifiable emission reduction targets across countries? How will differing national climate policies interface at the border? (i.e. border carbon adjustment policies)? The greater the global coordination, the more effective the impact on climate change, and the better the chance of consistent national policies.

The fact is that competitiveness and foreign policy have never been two solitudes. What is different now is that pervasive globalization, the digital revolution and the emergence of China as a superpower have linked them as never before.

Conclusion

Restoring Canadian competitiveness will require the public and private sectors to understand these trends and transformations and apply a competitiveness lens to how we respond to the emerging foreign policy situations and choices we will face. It will take greater public understanding of why it matters to them personally, not abstractly. Competitiveness is complex, it lacks captivating metrics, and it is long term in nature in a world consumed by simple messages and short-termism. But the value of informed public debate, where both the message and the messenger matter, is too often under-appreciated in public policy making.

Canadians are very proud of our status as a G7 nation, but too often forget that we no longer have a G7 military, nor a G7 economy. But building a highly competitive, tech savvy, talent laden economy with strong social principles would not only improve Canadians’ long-term living standards but also give Canada greater foreign policy influence in a world of combative superpowers. That is the restored competitiveness Canada should aim for, and the world clearly needs more middle powers like that in these unsettled times.

Kevin Lynch

The Honourable Kevin Lynch served as the Vice Chairman of BMO Financial Group from 2010-2020. Prior to that, he was a distinguished former public servant with 33 years of service with the Government of Canada, serving as Clerk of the Privy Council, Secretary to the Cabinet, Deputy Minister of Finance, Deputy Minister of Industry as well as Executive Director for Canada at the International Monetary Fund. Dr. Lynch is the past Chancellor of the University of King’s College, the past Chair of the Board of Governors of the University of Waterloo, a Senior Fellow of Massey College and a Trustee of the Killam Trusts. Since retiring from government, he has written over 140 policy Op Ed’s and articles and speaks frequently at conferences in Canada and abroad. He holds a B.A. (Mount Allison University), a Masters in Economics (University of Manchester), and a doctorate in Economics (McMaster University). He was made a Member of the Queen’s Privy Council for Canada in 2009, was appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada in 2011, has received 11 honorary doctorates from Canadian Universities and was awarded the Queen’s Golden and Diamond Jubilee Medals for public service.