Rethinking the Perceived Perils of Sovereign Government Debt

This issue of JSGS Policy Brief is part of a series dedicated to exploring and providing evidence-based analysis, policy ideas, recommendations and research conclusions on the various dimensions of the pandemic, as it relates here in Canada and internationally.

By Marc-André Pigeon, Assistant Professor, Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public PolicyIn its April 23rd edition, the policymaking and financial sector’s magazine of record, The Economist, featured an arresting cover image of a man carrying an enormous coronavirus on his back and climbing a stylized Sisyphean hill made of debt, dutifully following the direction of a red arrow pointing inexorably upwards. The headline? After the Disease, the Debt.

The Economist warns that “colossal” debt and “wild borrowing” from COVID-19 will exact a future toll in the form of some combination of higher inflation, “politically toxic” spending cuts or tax increases, crowded out private sector investment or worse yet, financial repression (“artificially” low interest rates). The message is clear: the adults in the room must “prepare for the grim business of balancing budgets later in the decade” or risk robbing the future of the “spare cash” needed to fight climate change, support our aging population or fight future pandemics.

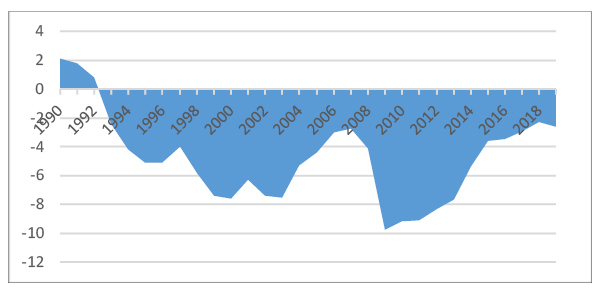

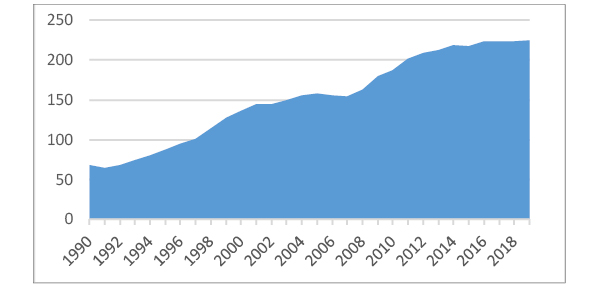

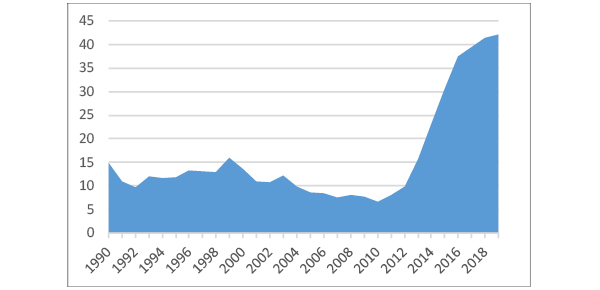

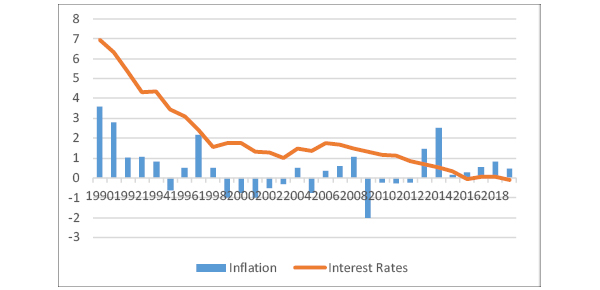

But what if there was another way of looking at these fiscal questions, one that said that most of what we have been told about sovereign deficits and debt is wrong? What if we knew there is never a financial constraint on a sovereign government’s ability to pay debt denominated in its own money, only an inflationary one? What if we could show that sovereign governments spend to tax rather than tax to spend? What if it was known that this alternative view had warned about unsustainable consumer borrowing long before it was fashionable, argued persuasively (against consensus) that central bank purchases of debt would not generate hyperinflation, and could readily explain the seemingly impossible Japanese pairing of decades worth of COVID-19 size deficits, the biggest public sector debt in the world, “debt monetization” through central bank purchases, disappearing interest rates and almost non-existent inflation (see Figures1-4).

Figure 1: Japan: Public Sector Deficits as a Share of GDP

If we knew all of that, we might approach fiscal policy matters as differently as Copernicus approached the movement of the planets, discarding the fiscal scolds just as Copernicus discounted those who insisted on the increasingly convoluted Ptolemaic model that put earth at its centre. And knowing this, we might shift some of our post COVID-19 energies away from fretting about accumulated accounting deficits (i.e., sovereign debt)—a disposition that is likely to worsen and lengthen our economic malaise—to more tangible and meaningful deficits like clean air and water, climate change, high quality child care, education and health care, reconciliation, sustainable infrastructure, and income inequality. We would play with real tradeoffs, not just their distributional manifestations.

But to get there, we would also need to overcome a lot of mischaracterizations of this set of ideas that go by the name modern monetary theory (MMT). And to do all of that, we would have to start the story from the beginning, where it all began, with money.

A Theory of Money

The conventional economics story says money arose as an efficient means of solving the “double coincidence of wants” problem: what if the butcher had no interest in what the candlestick maker’s was selling? Easy: people just had to settle on a means of exchange, ideally a metallic coin, that everyone would accept knowing they could buy what they really wanted, not what their neighbor happened to have. The transaction cost saving coin would have some sort of intrinsic value, was scarce, uniform, transportable and durable and could easily be added up and divided (Menger, 1950).

This functionalist story is nice, neat, simple and it turns out, ahistorical and not supported by the evidence (Wray, 1990, 1998, 2012; Goodhart, 1998). A growing body of work shows how money’s unit of account function—measuring who owes what to whom—originated out of temple societies that standardized measurements of commodities like wheat and barley (Hudson, 2004). Coin-type monies came much later (Ingham, 2000; Henry, 2004; Graber, 2012) and were pushed into society by powerful figures who paid soldiers in their monies. These were then taxed back, generating acceptance, value and imbuing the coins with a means of exchange function akin to the way economists usually think of money. In telling the story this way, MMT scholars emphasize money’s social embeddedness, distributional nature and draw attention to how money originates from authority and helps creates markets, not the other way around.

A Theory of Banking

In retelling the story of money, we also need to revisit the story of banking. Here again, the conventional story is simple, intuitive and appealing but more backwards than wrong. It suggests banks “intermediate” between savers and borrowers, taking money from Peter to lend to Paul. The more elaborate “fractional” reserve story suggests that banks lend out multiples of central bank “reserves” and don’t really need to precisely match deposits to loans.

It turns out both stories have the causality backwards. Instead of waiting for deposits or reserves to lend, banks lend first and obtain “reserves” second (Moore 1988; Werner, 2014; 2016; Bank of England, 2015). When you walk in for a home mortgage, your bank writes up a new loan (as an asset) and poof, creates new money in the form of the resulting deposit (a bank liability or IOU). When and if you move your money to another bank (maybe the house purchase went through), your bank now “owes” the deposit to the destination bank. If nothing else happened, your bank would have to settle its liability by borrowing from a surplus bank or from the central bank. Either way, the transaction takes place in neutral “third party” money we referred to earlier as reserves, which are just central bank IOUs. Note however that central banks always supply the needed reserves because otherwise, demand for reserves would exceed supply, interest rates would spike, and central banks would lose their main policy instrument.

None of this should be a big secret. In a different feature article, The Economist quoted the chairman of BNP Paribas, one of the world’s largest banks, as saying “Banks create money, and money is a sovereign good. States decide what we can do with it.” But somehow, few have digested the many policy implications of this understanding, one of which stands out for our purposes: contrary to the conventional story, sovereign deficits do not reduce the pool of available savings and push up interest rates, crowding out private investments. Backstopped by the central bank, private banks can always keystroke new money into being, constrained only by regulations and interest paid for reserves.

Taxation and Spending

If regulatory and market constraints are the only thing holding banks back from reckless lending, might it not be reasonable to think that maybe a sovereign government, with its own central bank and rule making powers, might have an even greater degree of latitude? You’d never know it by reading conventional accounts that emphasize the threat of “bond vigilantes” and debt downgrades. You’d also never know it from statements by academics and fiscal specialists routinely suggesting that government deficits can only be balanced by raising taxes or cutting spending. In its 2011 annual report on fiscal sustainability for example, the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) noted how at the time, federal (and provincial/territorial) finances were not sustainable and that policymakers would be required to “either raise taxes, reduce overall program spending, or some combination of both.” No third option was proffered, no acknowledgement made of the sovereign’s sovereignty, of its convenient access to a central bank.

And yet, MMT theorists point out that the Bank of Canada routinely funds government borrowing, buying up to 20% of all new debt issues outright in recent years, as Library of Parliament economists have pointed out. For MMT scholars, the willingness to downplay the “overt monetary financing” option, reinforced in macroeconomic textbooks (Samuleson et al 1988; Mankiw and Scarth, 1995) and any number of policy documents, only underlines a basic failure of conventional economics to understand a related point, namely that conceptually, government spending must come before taxation.

This is where the story of money really matters. If money’s value is shaped in part by demand arising from taxation, then money must find its way into the market through government spending and not the other way around (Bell, 2000). You can’t tax it back if it’s not there in the first place. Even if self-imposed rules make this less then obvious, careful analysis shows that the causality always runs from spending to taxation and not the other way around (Fullwiler 2010; Lavoie 2013). The moral of this story of course is that sovereign governments face no constraints in paying back debt issued in their own currency. They are not even compelled to issue debt to match deficit spending. That is purely a choice, albeit one appreciated by private sector entities that depends on the risk-free asset and stream of income (Mitchell, 2010).

The policy implications are clear: the issuance of debt is a choice that helps determine the distribution of future output. There is no fabled inter-generational challenge of “burdening our grand-children,” only an intra-generational distributional choice about who gets what now and how we are leaving a real legacy for our grandchildren—clean air, good parks, strong schools, good infrastructure, a more equitable society and ultimately, healthy and humane humans.

Politics and Inflation: In That Order

And now we find ourselves at the last redoubt of those who, when confronted with the evidence, retreat to saying they always knew that central banks could crank the printing press (a misleading but rhetorically evocative statement). But, they say, there is a larger question of politics and inflation that suggest this is not a viable option, at least in normal times.

Why? It seems economists are partial to a view that politicians suffer from a deficit bias, an unfortunate affliction that causes them to spend more or tax less in the pursuit of power, deficits be damned. And if politicians suffer from deficit bias, what stops them from demanding that central banks fund their reckless spending or tax cut plans? If central banks accede, then we will surely end up with hyperinflation reminiscent of iconic wheelbarrows scenes in Weimer Germany. Do we really want to be the next Venezuela? Better to stress the importance of central bank independence and keep quiet about the third rail of macro-economic policy: “money printing.”

This depiction of causality hinges on a belief that inflation is only a monetary phenomenon of too much money chasing too few goods—simple supply and demand with maybe a bit of velocity of money thrown in. If central banks fund government spend by “printing money,” then inflation will result. In a free-floating currency regime like Canada’s, the inflationary potential is worsened because, so the story goes, money printing devalues the currency and thus causes import prices to rise.

The MMT perspective suggests that the inflation is more complicated than that. The Japanese data cited earlier suggest as much: the Bank of Japan now holds 50% of government debt after decades of big deficits with consequences precisely opposite of those theorized, namely deflation and a relentlessly strong currency. Next, MMT reminds us that since banks also create money when they extend a loan, the conventional story must presume that central bank fueled government spending is inflationary but credit-fueled private sector spending somehow is not. But is that necessarily true? Is drawing on a line of credit (new money creation) to fund a vacation to Cuba or plastic surgery really more productive than the federal government drawing on the Bank of Canada to help provinces provide support to homeless people, child care and education? Could it be that the Japanese have spent their money wisely?

But the MMT inflation story goes deeper still. Since money has always been a way of keeping score, and irredeemably social rather than a neutral market tool, we can think of its value as both a barometer of distributional struggles set in the context of an institutional framework (Setterfield, 2005, 2006) as well as real productive capacity (Mitchell, 1998). In a more rigid social structure, we might expect deflation. In a more dynamic one where social relations and distributional debates are in flux and/or supply relationships stressed, we might get inflation. In this story, inflation could result from too much money chasing too few goods but also from widespread tax evasion, a supply shock like oil prices in the 1970s, the institutionalization of inflation-adjusted wage contracts, and/or an economy that lacks the real capacity to provide and fairly distribute the goods and services that people need. In short, it’s complicated.

Finally, some say that MMT makes sense for the United States because it makes the kind of money (US dollars) everyone wants and needs. No one is clamoring for Canadian dollars or the Argentinian peso. What then? This is arguably the most debatable point within the MMT research community, and a fruitful area of research. Some MMTers do worry that large deficit spending might in some circumstances cause currency devaluation and inflationary pressures; others however point to its salutary effect on the competitiveness of exports. But all MMTers agree that (a) these arguments presume that central bank-fueled government spending is more inflationary than bank credit-fueled private spending; and (b) countries with a free floating currency have far more degrees of freedom than is commonly assumed.

After COVID-19, An Adult Conversation

Does all this mean, as many have claimed, that MMT believes deficits do not matter? The answer is no. MMT says they matter because we choose a set of institutions that mirror every deficit with government debt, providing a guaranteed income to those who can afford them. They matter because of how they are spent. If they further the sustainability of our physical and social environment, they add to capacity, legitimacy and augment resilience; if they do the opposite, they set up the conditions for inflation and fragility. They matter because the words themselves (deficit, debt) trigger an emotional, visceral reaction associated with household debt, a point emphasized in research on the language of fiscal policy (Pigeon, 2009).

Policymakers and economists are fond of stressing the importance of “adult conversations,” recognizing unavoidable trade-offs that flow from decision-making. MMT theorists agree. But the adult conversation around the post-COVID world needs to start from a place where all the options are on the table, where there is transparency about real tradeoffs, where we don’t use household debt analogies that are misleading but convenient, and where we talk more openly about how decisions create winners and losers. In that sense, The Economist is right. After COVID, we need to talk about the resulting debt, not just the accounting artefact but also the real debt we owe each other in this shared space we call society.

ISSN 2369-0224 (Print) ISSN 2369-0232 (Online)

References

Bell, S. 2000. Do taxes and bonds finance government spending?. Journal of Economic Issues, 34(3), pp.603-620.

Fullwiler, S.T., 2010. “Helicopter Drops Are FISCAL Operations.” Available at SSRN 1725026

——. 2016. “The debt ratio and sustainable macroeconomic policy.” World Economic Review, 7, pp.12-42

Goodhart, Charles A.E. 1998. “The two concepts of money: implications for the analysis of optimal currency areas.” European Journal of Political Economy, Volume 14, 407-432.

Government of Canada. 2002. Debt Management Report. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/fin/migration/dtman/2002-2003/dmr03_e.pdf

——. Budget 2003. Available at: https://www.budget.gc.ca/pdfarch/budget03/pdf/bp2003e.pdf

Graeber, D., 2012. Debt: The first 5000 years. Penguin UK.

Henry, J.F., 2004. The social origins of money in Wray, L. Randall (ed.), Credit and State Theories of Money.

Hudson, M., 2004. The archaeology of money: debt versus barter theories of money’s origins. Credit and state theories of money: the contributions of A. Mitchell Innes, pp.99-127

Ingham, Geoffrey. 2000. “ ‘Babylonian madness’: on the historical and sociological origins of money.” In Smithin, John, ed. What is Money? New York: Routledge

Lavoie, M., 2013. The monetary and fiscal nexus of neo-chartalism: a friendly critique. Journal of Economic Issues, 47(1), pp.1-32.

Mankiw, N. Gregory and William Scarth. 1995. Macroeconomics (Canadian Edition). New York: Worth Publishers.

Menger, Carl. 1950. Principles of economics. New York: The Free Press.

——. (1892). “On the origins of money.” Economic Journal, Volume 2, 239-255.Mitchell, William. 2010. “Market Participants Need Public Debt,” Bill Mitchell Modern Monetary Theory Blog, available at: http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=10404

Moore, B.J., 1988. Horizontalists and verticalists: the macroeconomics of credit money. Cambridge University Press.

Pigeon, M.A.J., 2009. Conflict, consensus, convention: the depoliticization of Canada's macroeconomic discourse (Doctoral dissertation, Carleton University).

Samuelson, Paul A., William D. Nordhaus and John McCallum. 1988. Economics (Canadian edition). Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson Ltd.

Setterfield, M., 2005. Worker insecurity and US macroeconomic performance during the 1990s. Review of Radical Political Economics, 37(2), pp.155-177.

Setterfield, Mark. 2006. “Is inflation targeting compatible with post keynesian economics.” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 28:4, 653-671.

Tcherneva, P.R. 2006. “Chartalism and the Tax-Driven Approach to Money.” Handbook of Alternative Monetary Economics, Philip Arestis & Malcolm Sawyer.

Werner, R.A., 2014. How do banks create money, and why can other firms not do the same? An explanation for the coexistence of lending and deposit-taking. International Review of Financial Analysis, 36, pp.71-77.

——. 2016. A lost century in economics: Three theories of banking and the conclusive evidence. International Review of Financial Analysis, 46, pp.361-379.

Wray, Randall L. (1990). Money and credit in capitalist economies: The endogenous money approach. Brookfield, US: Edward Elgar.

——. 1998. Understanding modern money: The key to full employment and price stability. Brookfield, US: Edward Elgar.

——. 2012. “Introduction to an alternative history of money.” Levy Economics Institute, Working Paper 717.

Marc-Andre Pigeon

Marc-André Pigeon is an Assistant Professor in the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy, University of Saskatchewan campus. He holds a PhD in Mass Communications from Carleton University and has worked in a number of economics and policy-related positions, most recently as assistant vice-president of public policy at the Canadian Credit Union Association. He has also served as interim-vice president of government relations at CCUA, as a special advisor and senior project leader at the federal Department of Finance, and as lead analyst on several federal Parliamentary committees including the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance, the Standing Committee on Public Accounts, the Standing Committee on Banking, Trade and Commerce, and the Standing Committee on Agriculture and Forestry. Dr. Pigeon also worked as an economic researcher at the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College and started his career as a financial journalist at Bloomberg Business News.

His research interests include the study of co-operatives, behavioural economics/psychology, income distribution, money and banking, and fiscal and monetary policy.