Crime in Saskatchewan: The issue too many would rather ignore

If there is one subject that does more reputational damage to Saskatchewan than any other, even more than the weather and geography, it’s the province’s crime rate. For decades, Saskatchewan has struggled with levels of crime that have either led the nation, or been among the highest. The impact on public opinion of the province should not be underestimated. The problem is both one of perception and reality. What happens is people draw generalizations and apply them to their overall view of the province when statistics reflect a reality often over-represented in specific communities.

By Dale Eisler, Senior Policy Fellow, Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public PolicyIf there is one subject that does more reputational damage to Saskatchewan than any other, even more than the weather and geography, it’s the province’s crime rate. For decades, Saskatchewan has struggled with levels of crime that have either led the nation, or been among the highest. The impact on public opinion of the province should not be underestimated. The problem is both one of perception and reality. What happens is people draw generalizations and apply them to their overall view of the province when statistics reflect a reality often over-represented in specific communities.

The most striking example came in 2007, when Maclean’s magazine depicted the North Central area of Regina as crime- and violenceridden, labelling it “Canada’s worst neighbourhood”. In spite of the obvious facts behind the characterization of the community, it stirred an angry backlash. The journalist and magazine were denounced for doing a “drive-by” smear and ignoring positive aspects of North Central, and the city in general. This tendency of governments and others to downplay the truth, rather than face the facts and seriously engage with communities struggling to cope and working hard on improving their situation, has been a common reaction when confronted by the uncomfortable truth of crime rates. It reflects the fact no one quite knows what to do, other than manage the issue as best possible.

In recent months, the issue of crime again became a focus of public attention. The latest Statistics Canada data indicates Saskatchewan in 2015 had the highest overall crime rate among provinces. Moreover, of the major cities in Canada, Saskatoon and Regina had the highest rates of criminal code offences, including for homicide and aggravated assault. In a follow-up article this year, Maclean’s notes not a lot has changed from its 2007 portrait, with North Central accounting for 17 per cent of the city’s crime and only 4.5 per cent of Regina’s population. More recently, the subject was back again when the Saskatchewan Association of Rural Municipalities passed a controversial resolution saying “crime has increased substantially in rural communities” and called on the federal government to expand the rights of individuals to defend themselves and their property.1 The so-called “stand-yourground” resolution stirred an angry backlash from the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations. It was “shocked and disgusted” by what it saw as “the violent intentions behind the resolution” in the wake of a high-profile, tragic case last year when a young Indigenous man was shot and killed on a farmer’s property.

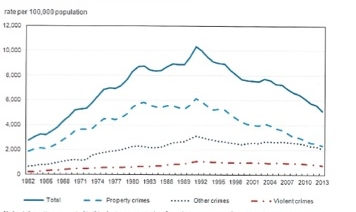

That’s the bad news. The good news is that during the last 20 years, crime rates in Canada, and in Saskatchewan, have actually declined. Rates increased in 2015, but the overall trend has been steadily downward. For Canada, the crime rate from the period 1998 to 2015 was at its peak in 1998 when it was 8,600 per 100,000 population, or 8.6 per cent. Aside from 2003, when the rate increased slightly, it has continued its decline until 2015 when it rose slightly to 5.5 per cent. The story for Saskatchewan over the same period is similar. The crime rate peaked at 16.4 per cent in 2003 and has declined every year since, except in 2015 when the rate increased to 12 per cent, a year-over-year increase of 5.1 per cent in criminal code violations.2 So there has been progress.

Chart 1: Police-reported crime rate, Canada, 1962 to 2013

Having said that, taking solace in Saskatchewan’s disproportionately large share of a smaller problem is cold comfort. The long-standing issue remains. In relative terms, Saskatchewan often tends to be an outlier from other provinces in the frequency and severity of crime. The exceptions are Nunavut, the Northwest Territories and Yukon, which historically have had significantly higher crime rates than the provinces.

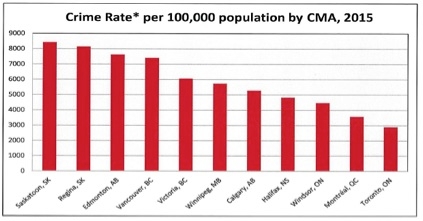

In its most recent data, Statistics Canada found in 2015 the rate of criminal code offences in Saskatchewan, including traffic violations, was 12,007.64 per 100,000 population, or slightly more than 12 per cent. The rate for Canada was 5,549.26, or 5.5 per cent. When traffic offences are excluded, the relative comparators don’t change. As Chart 2 indicates, in 2015 Saskatoon and Regina had the first and second highest crime rates among 11 major Canadian cities. Moreover, Saskatchewan is witnessing a rapid increase in drug offences, particularly a dramatic escalation in charges for possession and trafficking in methamphetamine.

Chart 2: Crime Rate* per 100,000 population by CMA, 2015

Drilling down into the numbers, Saskatchewan also ranks as an outlier in terms of crime severity. Based on the crime severity index, which measures changes in the level of severity of crime from year to year, with the base year of 2006 equaling 100, the Canadian rate in 2015 was 69.71. In other words, the national crime severity index actually dropped by more than 30 per cent since 2006. By contrast the Saskatchewan index rose by 36 per cent to 135.84 during the last nine years.3 The story isn’t any better when it comes to high-profile crime such as homicide. In 2015, the murder rate in Saskatchewan was 3.79 per 100,000 population, compared to a national rate of 1.68. Saskatchewan’s murder rate was exceeded only by the Northwest Territories.4 Among Canada’s large cities, Regina had the highest rate of homicide at 3.30 per 100,000 people, while Saskatoon had a homicide rate of 3.22. Again, it is important to note that since the early 1990s, the murder and attempted murder rates in Canada have been declining.

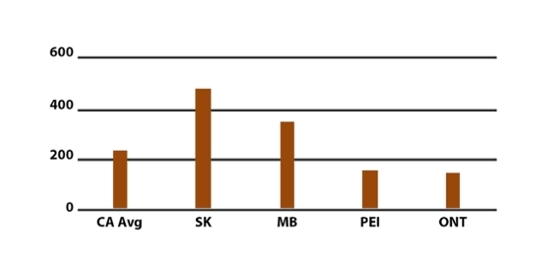

There are other troubling facts that are unique to Saskatchewan, such as our abnormally high rates of domestic violence, the highest HIV infection rates in the nation, elevated rates of impaired driving, and the recent drastic rise in drug offences, particularly related to methamphetamine.5

Chart 3: Reported family violence

The obvious question these facts raise is why? What is it about Saskatchewan that explains crime rates that regularly exceed national norms, and often are higher than our neighbouring provinces?

This is obviously a fraught subject. It inevitably leads to the complex intersection of many social, economic, cultural and racial issues that are deeply rooted in Saskatchewan and the nation’s history. But because an issue is difficult and multi-dimensional is no excuse for policymakers to avoid tackling it in a direct and multi-faceted way, and with the necessary conviction. Clearly, there are no easy answers or much better progress would have been made over the years in alleviating the anomalies of crime rates in Saskatchewan. Having said that, some can and will argue that progress has been and is being made, reflected in the reality that crime rates have been trending down for many years in Canada, and Saskatchewan. The policy question is can more be done?

A starting point in answering that question requires the admission that the reason, or reasons, for the decline are unclear. Is it attributable to a specific set of policy initiatives, and if so, which ones? There is not a uniform approach to dealing with crime, whether in a criminal justice, punitive approach with a focus on deterrence, or more broadly in terms of social and economic policy, or some combination of initiatives. The fact is the same decline in crime rates that has occurred in Canada, has also taken place in the United States and across much of Europe.

There is no shortage of research into what conditions tend to exist in high crime areas. While the findings are not entirely aligned, the vast consensus is that there is a direct correlation between poverty and crime. That’s not to say there aren’t other social causes, such as those relating to learned values as part of social conscience, mental health and drug use, which are crucial factors in criminal behaviour. But poverty, especially in modern, developed economies, is clearly a major ingredient. A University of Edinburgh study that followed 4,300 youth as they transitioned from childhood to adult “found that poverty had a significant and direct effect on young people’s likelihood to engage in violence at age 15, even after controlling for the effects of a range of other factors known to influence violent behaviour.”6 While both evidence and intuition would support the close link between poverty and crime, paradoxically in the U.S. crime rates have declined during a period when there has been growing income inequality and poverty.

Where there is a lack of clear, evidence-based research and ultimately policy is when it comes to the best approach to reduce crime. But assuming the determinants of crime are complex, and involve a range of economic and social factors, such as poverty and dysfunctional communities that create a sense of alienation and hopelessness that can lead to anti-social behaviour, so too must the policy approach be community-based, broad and co-ordinated enough that all the necessary tools are being used.7

The Way Forward

As for Saskatchewan, and its persistently high crime rates relative to other jurisdictions, the challenge can be easily stated: identify and implement a strategy that reduces the causes of crime. Reaching the objective is not so easy. It requires, first of all, the political will of policymakers and others to acknowledge the issue, focus public will and dedicate the energy and resources necessary to have a significant positive impact. Unfortunately a key reason the issue has never received the attention it deserves is because successive governments are unwilling to invest significant resources, and therefore political capital, in tackling a subject that defies easy solution.

Given the complexity of what are considered the social and economic determinants of criminal behaviour, any serious crime reduction strategy involves an integrated spectrum of measures that includes a criminal justice system focused on deterrence, prevention and rehabilitation and a co-ordinated suite of community policies that attack the underlying causes of crime. To its credit, the Saskatchewan government recognized the scope of the challenge and in 2012 launched its Building Partnerships to Reduce Crime initiative (BPRC). The effort uses a “risk driven crime reduction partnership approach” that focuses on “reducing victimization and improving community safety outcomes” by identifying risk factors and bringing together the various agencies and community groups to intervene and address those influences.

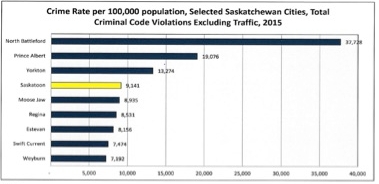

Chart 4: Crime Rate per 100,000 population, Selected Saskatchewan Cities, Total Criminal Code Violations Excluding Traffice, 2015

It is a daunting challenge that involves some uncomfortable truths. One is that Indigenous people are grossly over-represented in the criminal justice system. First Nations, Métis and Inuit people comprise only 4.3 per cent of the Canadian population but account for 24.4 per cent of the total inmate population.8 It is the outcome of countless social and economic factors, many related to policies in Canada’s colonial past – from state policies of assimilation, cultural eradication manifested in residential schools and the breakup of Indigenous families as part of the “Sixties Scoop”, to social and political exclusion. In Canada the rate of incarceration for Indigenous people is 10 times higher than for the non-Indigenous population. In Saskatchewan, an Indigenous person is 33 times more likely to be incarcerated. To put that in perspective, in the U.S. black men are six times more likely to be imprisoned than white men.9 No wonder some call Canadian prisons the “new” residential schools.

Aboriginal people are far more likely to be crime victims than non-Aboriginals. A total of 28 per cent of Aboriginal people, compared with 18% of non-Aboriginals, reported being the victim of crime. The fact that the Aboriginal population in Canada is younger than the non-Aboriginal population accounts for some of the difference in overall victimization, but it does not explain it entirely: “When controlling for various risk factors, Aboriginal identity by itself did not remain associated with increasing one’s overall risk of violent victimization. Rather, the higher rates of victimization observed among Aboriginal people appeared to be related to the increased presence of other risk factors among this group—such as experiencing childhood maltreatment, perceiving social disorder in one’s neighbourhood, having been homeless, using drugs, or having fair or poor mental health.”10

Given the evidence, Saskatchewan needs a new, comprehensive and cohesive approach. The basic elements are there in the efforts of the BPRC, which uses a hub model to bring together the community agencies and groups necessary to address the determinants and effects of anti-social and criminal behaviour. But it is an initiative that lacks the funding and resources to have the impact it could. So, what’s needed is the public acknowledgement by policymakers that the province has a significant issue with crime and dealing with it is a priority. Until there is an expression of political will, nothing will happen. The challenge is multi-layered and requires the participation, resources and commitment of federal, provincial, Indigenous, municipal, police, educators and community-based groups.

Next comes dealing with the reality on the ground where crime is tearing the social fabric. With drugs and related criminal gang behaviour disrupting neighbourhoods and communities, the violent and dangerous criminals need to be taken off the street through professional police and criminal justice measures. But police and the justice system cannot solve crime or the social and economic issues that are at its roots. Unfortunately, too often police are forced to deal with social issues they are ill-equipped — and should not be expected — to address.

The approach needs to focus on risk reduction. That means zeroing in on critical social factors, such as mental health and addictions, domestic violence, parenting, school absenteeism and literacy. Those are often evident in communities where there are high rates of poverty, which day-to-day can erode hope, and life without hope for a better life can be corrosive to the social fabric of a community. If there is not a sense of opportunity, if people believe they are trapped in their condition, then escaping it can lead to desperation.

Clearly, the range of issues that needs to be addressed requires a strategy that brings together multiple participants around a plan that is both holistic and focussed in its approach. There is no shortage of data that can point to the determinants that increase the probability of anti-social and criminal behaviour. Those factors need to guide how intervention takes place, by whom, where and when. It should begin with pilot projects that launch a coordinated and multifaceted plan in a few targeted communities where crime rates and their outcomes are most evident. Through trial and, yes error, on the ground, it will be possible to better determine the best practices.

It is difficult to imagine a more important or complex social and economic challenge to address. But “because it is hard” is no reason for not acting. That excuse has been used for years and simply ignoring it or attacking those who raise the uncomfortable truth is no longer good enough. It’s time for serious leadership on an issue that people know is important, even if they’d rather not talk about it.

Reference

1 SARM resolution 34-17A, 2017

2 Statistics Canada, CANSIM, Table 252-0051

3 Statistics Canada, CANSIM, Table 252-0052

4 Stats Can summary table, Homicide offences, number and rate, by province and territory

5 Prince Albert police battling “scourge” of crystal meth, Saskatoon StarPhoenix, July 25, 2016

6 The Link Between Poverty and Crime, Criminal Law and Justice Weekly, Jan. 22, 2016

7 p. vii, Crime Prevention and Community Safety: Trends and Perspectives, 2010, International Centre for the Prevention of Crime

8 p. 36, Office of the Correctional Investigator, 2014-15 annual report

9 Canada’s Prisons Are the New Residential Schools Maclean’s Magazine, Feb. 2016

10 http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2016001/article/14631-eng.htm

Dale Eisler

Dale Eisler has an extensive background in the federal public service and Canadian journalism. After a 25-year career in journalism with Saskatchewan and national publications, Dale spent 15 years in various senior roles with the Government of Canada, most recently as Assistant Deputy Minister for the Energy Security Task Force at Natural Resources Canada. Prior to that he spent four years serving as Canada’s Consul General in Denver, CO . Before his posting in the U.S., Dale was Assistant Secretary to the federal cabinet for Communications in the Privy Council Office and began his role in Ottawa as Assistant Deputy Minister for Communications in the Finance Department. He received the 2013 Joan Atkinson Federal Public Service Award of Excellence. He is the author of three books, including “False Expectations, Politics and the Pursuit of the Saskatchewan Myth” and, most recently in 2010, the historical fiction novel “Anton, a young boy, his friend and the Russian Revolution.”

People who are passionate about public policy know that the Province of Saskatchewan has pioneered some of Canada’s major policy innovations. The two distinguished public servants after whom the school is named, Albert W. Johnson and Thomas K. Shoyama, used their practical and theoretical knowledge to challenge existing policies and practices, as well as to explore new policies and organizational forms. Earning the label, “the Greatest Generation,” they and their colleagues became part of a group of modernizers who saw government as a positive catalyst of change in post-war Canada. They created a legacy of achievement in public administration and professionalism in public service that remains a continuing inspiration for public servants in Saskatchewan and across the country. The Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy is proud to carry on the tradition by educating students interested in and devoted to advancing public value.