Ex-Pat Canadians and the Right to Vote

From time to time, Canadian policy makers have addressed the question of who should have the right to vote. Initially thought of as a “privilege” to be granted a select few, the vote is now widely understood in Canada, as in other advanced democracies, as a “right” of citizenship. But how universal should that right be? Should all citizens enjoy it, or simply those not denied it by statute or court ruling (or both)? If an individual or group is denied the vote, can such a limitation be demonstrably justi ed in a free and democratic society as allowed by section 1 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms?

By John Courtney, Professor Emeritus of Political Studies and Senior Policy Fellow, Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public PolicyFrom time to time, Canadian policy makers have addressed the question of who should have the right to vote. Initially thought of as a “privilege” to be granted a select few, the vote is now widely understood in Canada, as in other advanced democracies, as a “right” of citizenship. But how universal should that right be? Should all citizens enjoy it, or simply those not denied it by statute or court ruling (or both)? If an individual or group is denied the vote, can such a limitation be demonstrably justi ed in a free and democratic society as allowed by section 1 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms?

These questions recently surfaced in a case heard by the Court of Appeal for Ontario. In Frank v. Canada (Attorney General) [2015 ONCA 536] a judgment was issued upholding the restrictions contained in the Canada Elections Act on the right of expatriate Canadians to vote. The Act denies the vote to Canadians who

have lived outside the country for ve consecutive years or more. Although the Court found that the restriction violated the Charter guarantee of the right to vote (s. 3), it was nonetheless saved by s. 1 as a reasonable limit that could be “demonstrably justi ed in a free and democratic society.”

That decision overturned an earlier ruling of a trial court judge in which the restriction was struck down. The challenge had been mounted by two Canadians who had lived and worked in New York State for most of their adult lives. They discovered they were ineligible to vote in the 2011 federal election and, the court was told, declared their intention to return to Canada if suitable employment could be found.

The effect of the restriction of Canada Elections Act (S. 222 [1]) was to deny the franchise to an estimated 1.4 million expatriate Canadians. The relevant section reads:

222. (1) The Chief Electoral O cer shall maintain a register of electors who are temporarily resident outside Canada in which is entered the name, date of birth, civic and mailing addresses, sex and electoral district of each elector who has led an application for registration and special ballot and who

(a) at any time before making the application, resided in Canada;

(b) has been residing outside Canada for less than ve consecutive years immediately before making the application; and

(c) intends to return to Canada to resume residence in the future.

With the Appeal Court ruling, the Canada Elections Act remains in e ect for the 2015 federal election. We may not, however, have heard the last word on this issue. The 30-year record of successful Charter-based challenges to restrictions on the right to vote by Canadian citizens suggests appeal of the Ontario ruling to the Supreme Court of Canada on the heels of this year’s election remains a strong possibility.

An Evolving Franchise

The colonies that created Canada in 1867 inherited their electoral institutions from the “Mother country.” These included the familiar rst-past-the-post system. At the outset election machinery was rmly in the hands of the party in o ce, and it was the governing party that compiled voters’ lists, appointed election o cials, and designed electoral districts. Those elements gave way in the early to mid-20th century to substantial electoral reforms, starting with the creation in 1920 of the non-partisan electoral agency we know as “Elections Canada” and ending with the approval in 1964 of legislation guaranteeing independent, arms-length electoral boundary commissions every ten years.

“Voter eligibility” was the component of the electoral system that has been the slowest to change, in large measure because it was the most prone to discriminatory and arbitrary actions by governments. Gradually over the course of 135 years it moved from a restrictive, narrowly de ned entitlement at the outset to what is now, domestically at least, a universal right subject only to age (18) and citizenship (Canadian) limitations.

The changes made to the franchise laws have been the product of two historically distinctive, but nonetheless pronounced, in uences. For the rst century after Confederation the franchise slowly expanded in response to events and changing social values of the time, and for the past three decades the courts’ interpretation of the democratic rights included in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms has completed what is arguably now one of the most inclusive franchises in the world.

Who should (or should not) be entitled to vote: 1867 to 1982

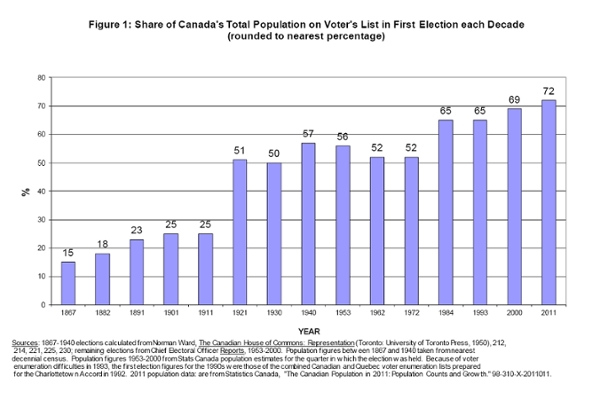

At the time of Confederation the right to vote was limited to those who were said to have a nancial stake in society: male property owners, 21 year of age or more. Females, non-property owning males, aboriginals, racial minorities, and various others had no vote. Not surprisingly, the share of the total Canadian population eligible to vote in federal elections was exceedingly small: 15% to be precise. (See Figure 1 for a decade-by-decade comparison of the percentage of all Canadians entitled to vote).

With time and evolving social attitudes (and with provinces often taking the lead) the voters’ lists expanded. How attitudinal di erences and provincial leadership could lead to changes in voter entitlement was best exempli ed by the enfranchisement of women in Canada. Between 1916 and 1919 seven provinces responded to pressure from church, women’s, and public interest groups and granted the vote to women 21 years of age and older for provincial elections. When Ottawa followed suit in 1920, the electorate e ectively doubled.

It was not until after the Second World War, however, that the barriers to voting based on race and religion were removed at both the federal and provincial levels. The newly enfranchised included those who had long been denied the vote, notably Canadians of Chinese, Japanese, and Hindu (interpreted broadly to encompass several South Asian groups) ancestry. Parliament in 1960, again following the lead of several provinces, extended the vote to status Indians, the last of Canada’s Aboriginals to be granted the vote.

The pre-Charter changes to the federal franchise concluded on the heels of the student riots in Paris and other European capitals in the late 1960s. The Trudeau Government moved to avert the possibility of what it called “intergenerational con ict” by lowering the voting age in federal elections from 21 to 18 years of age. That added a further two million Canadians to the electoral rolls – the largest single additional group since women were enfranchised 50 years earlier.

The Charter, the Courts, and the Right to Vote

The Charter, adopted in 1982, ushered in a new, constitutionally entrenched, instrument for the expansion of the franchise. Section 3 of the Charter reads:

3. Every citizen of Canada has the right to vote in an election of members of the House of Commons or of a legislative assembly and to be quali ed for membership therein.

Canada’s courts have interpreted that section in such a way as to construct a generous, inclusive, and (domestically at least) universal franchise. Among the Charter challenges to voting restrictions contained in the Canada Elections Act heard so far by the courts, three have been decided either by the Supreme Court of Canada or the Federal Court of Canada. All three decisions held that a particular prohibition on voting contained in the Canada Elections Act was unconstitutional: those denying the vote to federal judges (1988), the mentally disabled (1988), and prisoners (2002).

However small these additions to the electoral rolls may have been in absolute terms, they nonetheless helped to increase the share of Canada’s total population eligible to vote in a federal election to its highest point ever – 72%, or nearly ve times what it was in 1867. (Figure 1).2

The language used in the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in the 2002 prisoners’ right to vote case (Sauvé v. Canada [Chief Electoral Officer] S.C.C. 68) was instructive about the importance the Court attached to a broad and generous interpretation to the right to vote. In the words of the Chief Justice the disenfranchisement by elected representatives of a “segment . . . of the population nds no place in a democracy built upon the principles of inclusiveness, equality, and citizen participation.” (Sauvé, 2002, 4, emphasis added).

Limiting the Right to Vote of ex-Pat canadians: Pros and cons

At the Appeal Court in the Frank case the Attorney General presented several reasons for denying the vote to expatriate Canadians who have lived abroad for more than ve consecutive years. Among those are:

-

The primacy of residence (geographically de ned electoral districts and local polling stations) serves as the basis of Canada’s electoral system. The residency requirement “preserves the Canadian social contract.” [A.G. Factum, para. 45.] 3

-

The granting of the vote in 1993 to non-resident Canadians who intend to return to Canada within the ve-year limit ensures a measure of fairness in the electoral process vis-à- vis resident electors.

-

Exemptions to the ve-year limitations on voting abroad are provided for Canadians posted overseas to military and diplomatic missions.

-

Canadians resident in Canada, unlike those abroad, are full participants in Canadian civic society, pay an array of taxes levied by governments at various levels, and are required to obey all domestic laws.

-

The great majority of Canadian laws do not apply extraterritorially and, save for a treaty with a foreign state, the laws of Canada cannot be enforced abroad.

-

Comparable Westminster-based parliamentary systems impose some limit on external voting by non-resident citizens, ranging from three years in New Zealand to fteen in the UK.

-

The European Court of Human Rights, in a challenge to the UK’s limitation on voting of non-resident citizens, ruled that the franchise should be con ned to those with a “close connection” with the UK who would be “most directly a ected by its laws.” The limit to the UK vote was held to be “proportionate to the legitimate aim pursued.” [A.G. Factum, para. 93.]

-

The right to vote is not absolute. “It can and must be limited,” the Attorney General stated, citing the 18-years of age restriction on the franchise as one example of a justi ed limitation on the right to vote. [A.G. Factum, para. 115] 4

The case against denying the vote to expatriate Canadians is based on several claims, many of which were outlined in the trial court judgment in the Frank case and later accepted by the Appeal Court judge in his dissent:

-

According to the trial judgment, “many Canadians living abroad ... have tax obligations in Canada,” and some may contribute to or receive bene ts from the CPP and the OAS Programs. [Frank et. al. v. AG Canada, 2014 ONSC 907, paras. 27 and 28].

-

Non-resident Canadians “can and do live with the consequences of Parliament’s decisions” and may well be subject to Canadian law even while living abroad. [para. 86].

-

Residence is not “an essential and implicit precondition to a citizen’s right to vote” in the Canada Elections Act. Instead it is a mechanism for regulating the voting process. [para. 85].

-

Members of the Canadian Armed Forces (both inside Canada and abroad), diplomatic service personnel and their families posted outside Canada, and incarcerated electors in Canada are free to choose to have their ballots counted in “places they have never lived,” thereby putting the residency argument further into question. [para. 36].

-

According to the Appeal Court’s dissenting justice, the social contract that is said to be the link between entitlement to vote and residency is an “artifice” conjured up by the Attorney General. [Frank v. Canada (Attorney General), para. 202] 5

- The Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing [1991], the Chief Electoral Officer for Canada [2005], and the Commons Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs [2006] all recommended enfranchisement of expatriate Canadians.

What now?

“The history of democracy is the history of progressive enfranchisement,” in the words of the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada in 2002. [Sauvé, para. 33.] That claim is supported by Canada’s record of gradually widening the “right to vote” since Confederation. Will that “progressive enfranchisement” once again be invoked in relation to expatriate Canadians if Frank is appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada?

Will a law (in this case s. 222[1] of the Canada Elections Act) that has been found to be in violation of a Charter guarantee nonetheless be saved by section 1 of the Charter? Can that violation be “demonstrably justi ed in a free and democratic society”?

Two courts have wrestled with those last two questions, in both cases employing the Oakes test for Charter violations. They have reached di erent conclusions: the trial court struck down the impugned section and the appeal court upheld it.

The Oakes6 test requires courts to weigh the evidence in relation to the following criteria:

-

Is the objective of the impugned law both “pressing and substantial”?

-

Is the impairment of a Charter right “rationally connected” to its objective; is it “minimal;” and is the e ect of the impairment “proportionate” to the objective?

On further appeal, many of the questions already addressed by the courts will once again be raised. Of those, three will bear watching: Does the social contract theory have legitimacy in a constitutional challenge such as this? Is there a rational connection between the limitation on expatriate voting and the preservation of the integrity of Canada’s electoral system? And will the court employ the same reasoning to the extension of the franchise to the last remaining disenfranchised “segment . . . of the population” that it did in the 2002 Sauvé case?

References

1Sources: 1867-1940 elections calculated from Norman Ward, The Canadian House of Commons: Representation (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1950), 212, 214, 221, 225, 230; remaining elections from Chief Electoral Officer Reports, 1953-2000. Population figures between 1867 and 1940 taken from nearest decennial census. Population figures 1953-2000 from Stats Canada population estimates for the quarter in which the election was held. Because of voter enumeration difficulties in 1993, the first election figures for the 1990s were those of the combined Canadian and Quebec voter enumeration lists prepared for the Charlottetown Accord in 1992. 2011 population data: are from Statistics Canada, “The Canadian Population in 2011: Population Counts and Growth.” 98-310-X-2011011.

2The biggest single contributor to voter eligibility as measured against the total Canadian population since the enfranchisement of women has been the struc- tural age shifts found in each decade’s census. These are captured in the de- nominator of the equation and are most obvious between 1953-1972 when the great majority of baby boomers were not yet eligible to vote; in 1984 following the enfranchisement of 18-21-year olds; and in 2011 with an aging population.

3The Appeal Court’s majority drew support from a relatively new concept in Canadian constitutional law. Referred to by the Supreme Court in Sauvé [2002], a social contract is said to define a reciprocal relationship between electors and legislators. [Factum for the Appellant, the AG of Canada, 7 August 2014, sum- marizes the “social contract” in para. 53.]

4In Fitzgerald v. Alberta [2002 ABQB 1086], a Court of Queen’s Bench decision upheld the ban on voting of Canadian citizens under the age of 18.

5In the opinion of one critic, the social contract amounted to a substitution of political theory for legal analysis. See Kate Andrews, “The ‘Social Contract’ and the Law,” http://canliiconnects.org/en/commentaries/37662, 23 July 2015.

6R. v. Oakes [1986] 1 SCR 103.

John Courtney

John Courtney is Professor Emeritus of Political Studies and Senior Policy Fellow of the Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon. A former President of the Canadian Political Science Association and Co-editor of the Canadian Journal of Political Science, he is the author or editor of ten books and numerous articles and chapters in books on elections, redistricting, leadership selection, and representational and electoral systems. His two most recent books are Elections [UBC Press, 2004] and The Oxford Handbook of Canadian Politics [Oxford University Press, co-edited with David E. Smith, 2010].

People who are passionate about public policy know that the Province of Saskatchewan has pioneered some of Canada’s major policy innovations. The two distinguished public servants after whom the school is named, Albert W. Johnson and Thomas K. Shoyama, used their practical and theoretical knowledge to challenge existing policies and practices, as well as to explore new policies and organizational forms. Earning the label, “the Greatest Generation,” they and their colleagues became part of a group of modernizers who saw government as a positive catalyst of change in post-war Canada. They created a legacy of achievement in public administration and professionalism in public service that remains a continuing inspiration for public servants in Saskatchewan and across the country. The Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy is proud to carry on the tradition by educating students interested in and devoted to advancing public value.