Who should own land in Saskatchewan?

In December 2013, the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB) purchased approximately 115, 000 acres of farmland from an investment company, Assiniboia Capital LP., for $128 million - the single largest sale of farmland in Saskatchewan’s history. The transaction generated substantial media attention and touched off a public debate about the role of institutional investors in the farmland market.

By Annette A. Desmarais; Darrin Qualman; André Magnan; Nettie WiebeIn December 2013, the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB) purchased approximately 115, 000 acres of farmland from an investment company, Assiniboia Capital LP., for $128 million -- the single largest sale of farmland in Saskatchewan’s history. The transaction generated substantial media attention and touched off a public debate about the role of institutional investors in the farmland market.

The sale is only one example of a larger trend whereby investors have been purchasing Saskatchewan farmland in recent years. Especially since the global financial crisis of 2008, some investment experts have touted farmland as an appealing ‘asset class’. Farmland is considered a good store of wealth, an effective hedge against inflation, and a source of both capital gains and income from rent – referred to by some as being ‘like gold with yield’ (Fairbairn 2014).

Saskatchewan is particularly attractive as a target for farmland investment because the province has a highly industrialized agricultural industry, well-developed infrastructure, a stable political environment, and relatively cheap land. Reasonably strong farm incomes and rising farmland values – prices increased by 128% between 2007 and 2014 (FCC 2015) -- have added to the interest in acquiring Saskatchewan farmland.

At the same time, large-scale purchases of farmland by non-farmers raise important issues for rural communities, the agricultural sector and Saskatchewan citizens generally. Farmland is not only a valuable natural resource and the foundation of the province’s agricultural economy, it is closely bound with the identity, culture, and economic security of farm families. As such, the issue of who should own farmland in Saskatchewan generates a great deal of debate.

There are a number of key questions Saskatchewan people should consider carefully:

- Is investor ownership eroding the relationship between farm families and the land they work?

- Are investors speculating on farmland, and if so, is this driving up the price of land beyond what is reasonable?

- Does outside investment in farmland create unfair competition for existing farmers who wish to buy land to expand their operations? How does the influx of investor funds affect young people who want to farm and/or are just starting their farming careers?

- What do large-scale land acquisitions by non-farmer investors mean for land use, the environment and rural communities?

- Are we witnessing the beginning of another structural change in Saskatchewan farming—a move to a model where one group or class in society owns the land, and another works it?

These and many more questions have been raised by politicians, farm organizations, commentators and citizens of Saskatchewan. The ongoing public debate prompted the Government of Saskatchewan to launch a review of the legislation regulating farmland ownership and invite contributions from the general public.

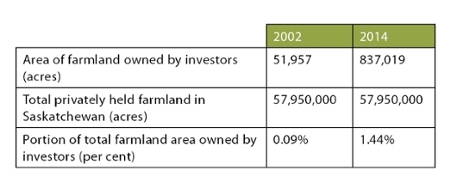

To date, however, there has not been a careful review of the extent to which farmland ownership patterns have actually changed. We address this information gap by providing a snapshot of farmland ownership in two years: 2002 and 2014. Using detailed, parcel-by-parcel data obtained from the province’s Information Services Corporation (ISC), we document the extent of Saskatchewan farmland ownership by non-farmer investors, investment companies, public pension plans and farmer/investor hybrids (all of which hereafter referred to collectively as “investors”). Furthermore, we use Geographical Information Systems (GIS) mapping techniques to reveal the spatial distribution of investor ownership. The years we have chosen allow us to compare the situation before and after the last major legislative change made to farmland ownership rules.

Until the end of 2002, the Farm Security Act restricted ownership of farmland to Saskatchewan residents (very small parcels exempted). The NDP government changed the Act in 2002 to allow Canadian citizens, permanent residents, and 100% Canadian-owned companies to acquire an unrestricted amount of farmland. Our analysis shows that investor ownership of Saskatchewan has increased very rapidly since 2002.

While the extent of investor ownership is small compared to the total area of farmland in the province, the activity of non-farmer investors is likely having a significant impact on the farmland market and local communities in some Rural Municipalities (RMs). We present our principle findings in the next section and then provide a discussion of the policy issues raised by changing patterns of farmland ownership.

Significant shifts in land ownership

Between 2002 and 2014, the amount of Saskatchewan farmland owned by investors increased 16-fold. Holdings by investors increased from 51,957 acres in 2002, to 837,019 acres in 2014 (Table 1). After 2002, investors dramatically increased the rate at which they accumulated Saskatchewan farmland.

Moreover, some of these entities are accumulating very large holdings. In 2014, three investors each owned more than 100,000 acres. The first is a private investor: Robert Andjelic, and his wholly-owned Andjelic Land Inc. Our data show Mr. Andjelic and his company owning 160,858 acres, though recent media reports put the figure at 180,000 acres. The second entity holding more than 100,000 acres is 101138678 Sask. Ltd., a company owned by the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB). The third very large entity is HCI Ventures Ltd., an investment vehicle controlled and largely owned by Alberta’s Hokanson family. In contrast to these holdings of more than 100,000 acres, the largest private landholding in 2002 was 24,296 acres, owned by the Hutterian Brethren Church Of Hillcrest—a collectively owned, communal farm.

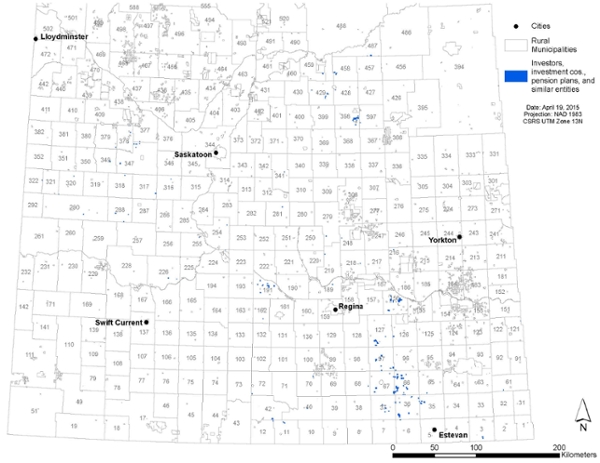

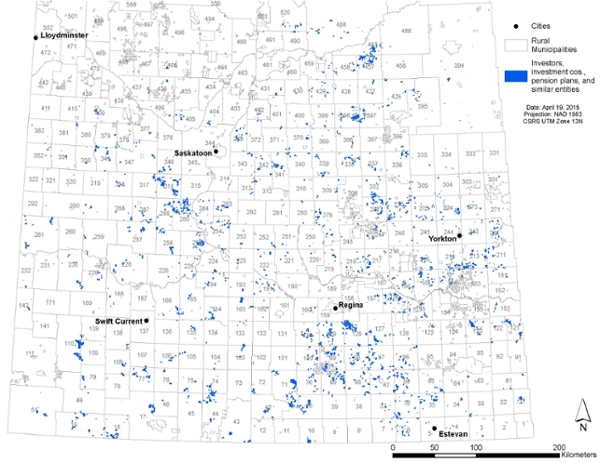

Figures 1 and 2 map the locations of the land parcels owned by investors in 2002 and 2014, respectively. In both Figures, the blue squares indicate parcels owned by investors, the grey lines represent boundaries of the numbered RMs, and the smaller grey squares and grey-outlined areas represent land excluded from RM jurisdiction, including First Nations reservations, cities, incorporated towns and villages, and parks.

Comparing Figures 1 and 2, the sixteen-fold increase in the amount of land owned by investors is plainly visible. Figure 2 also shows a clustering of investor-owned farmland parcels and the greater degree of investor ownership in some RMs, such as those south of Regina, southwest of Saskatoon, and around Yorkton. (We have yet to develop a systematic analysis of this clustering or its causes.)

In several RMs, investors own a significant portion of the farmland. In 53 RMs (of the 295 in total), investors own more than 3 per cent of farmland. Our research on land holdings for the province indicates that the amount of land owned by investors ranges from 0 per cent to 9.3 per cent. In 16 RMs, investors own more than 5 per cent. While these percentages indicate high levels of investor activity, they may actually understate the extent of that activity. Only a small portion of land is bought and sold at arm’s length each year—put on the market and sold outside of the family that owns the land. Thus, for investors to acquire 5 or 8 per cent of the farmland in a given RM over a 12-year period, investors may have had to purchase 10 or 20 per cent of the farmland offered for sale in arm’s-length transactions. In many RMs, investor purchases have likely had a significant effect on local land markets, local farmers, and surrounding communities.

In addition to the phenomenon of increased rates of farmland purchases by investors, our research also sheds light on a second phenomenon: increased concentration of ownership. In 2014, the four largest private owners (again, excluding governments, First Nations, etc.) owned 0.82 per cent of Saskatchewan farmland: 472,964 acres. This share is up six-fold from 2002, when the largest four owned just 0.13 per cent: 74,549 acres. We also note that the largest single landowner in 2014 owned 160,858 acres—twice as much as the four largest together owned in 2002. In 2002, three of the four largest private landowners in the province were Hutterite Brethren churches/colonies and the fourth was an investment company. In contrast, in 2014, all four of the four largest entities were investors.

So in summary, in 2002, investors owned almost no land in Saskatchewan. Twelve years later, their holdings are increasing rapidly and appear likely to surpass one million acres in the next two or three years. A growing number of entities own more than 100,000 acres each and initial indications are that farmland ownership overall is becoming more concentrated. Finally, given the clustering of purchases by investors, it is likely that the effects on local farmers, communities, and on farmland prices will be uneven and, in some areas, large and potentially negative.

Policy issues and options

The entry of non-farm investors into the farmland market has provoked an important debate about farmland ownership rules in Saskatchewan. A variety of stakeholders will no doubt contribute to the government’s current review of the Saskatchewan Farm Security Act. We hope to contribute to this discussion by broadening the terms of debate somewhat. Specifically, we highlight the need to reconsider some fundamental and recurring land policy questions that have largely been neglected in the debate.

Land ownership continues to be an important determinant of economic and political power, despite economic diversification and urbanization. The legislation governing land both reflects and shapes how land is viewed and used, and also who gets to own and use it. As such, land legislation facilitates different models of agriculture.

The current policy discourse is taking place in the context of a long history of indigenous peoples living on this land. The dispossession and displacement of indigenous peoples by settlers constituted a radical shift in the use and role of land, moving it from traditional territories occupied by peoples to newly deeded parcels owned by individuals. The Dominion Lands Act privatized land, making it a marketable commodity. It also instituted patriarchal ownership patterns by excluding women, with very few exceptions, from eligibility for ‘homesteads’. A major incentive drawing settlers into Saskatchewan was the promise of land ownership with the attendant security of tenure and the prospect of a more secure future.

By restricting farmland ownership to provincial residents, the Farm Security Act of 1974 seemed to affirm the value of the relationship between land ownership and security of tenure. As there were no restrictions on farm size or how much land an individual or corporate entity could own, however, the 1974 law did not prevent the on-going process of farm concentration, as farm size increased and farm numbers declined. Yet, by restricting farmland ownership to residents of the province, the legislation weighted social investment — living in, and contributing to, Saskatchewan communities — over capital investment. The 2002 policy change reflected a shift by giving priority to capital investment in farmland and broadening the residency/citizenship requirement for ownership to all Canadians.

In reflecting on the current review of farmland ownership rules, we propose the following fundamental questions: What are the key values farmland policies are meant to protect and enhance? What does a flourishing, economically competitive, ecologically sustainable, adequately capitalized, socially just and vibrant agriculture sector require? What objectives are the policy revisions supposed to meet?

Critical consideration of some policy objectives

Our research points to two very different policy directions that have different objectives and impact: Focusing on maximizing financial investment; or, Prioritizing social investment in agriculture, farm families and rural communities. A trade-off exists between these two policy directions. Prior to 2002, that trade-off was resolved largely in favour of social investment, via restrictions that limited farmland ownership to Saskatchewan residents. After 2002, that trade-off was resolved differently, with an apparent focus on enlarging the potential farmland buyer pool with the aim of increasing land prices and investor activity. The current provincial consultations should take into consideration the trade-off between two types of investment.

- Prioritize attracting and maximizing financial investment

- Maximize financial investment: This could be accomplished by removing restrictions on foreign investors. The increase in land values would mean a better retirement package for those leaving farming. The added capital investment in land will likely result in higher concentration of ownership. However, wouldthis advantage Saskatchewan agriculture and the people of the province significantly? Would this approach guarantee a much-needed new generation of young farmers in the province?

- Attract financial investment but restrict the origins/citizenship of the investors: The current policy, which restricts ownership to Canadians, facilitates the flow of out-of-province capital into farmland while intervening in the land market. Given the apparent current effects on land prices and local control, is the restriction to Canadian investors sufficient? Do Saskatchewan residents want to see more land transferred into the hands of non-farmer, out of province investors?

- Attract financial investment, but place added restrictions based on types of investors (i.e. pension funds, foreign funded corporate entities, etc.): While focusing on increasing capital investment, such restrictions define which kinds of investors are acceptable. What should be the key criteria? Size of the investment fund? Disposition of its earnings? For example, much like the oil and gas industry, if investors are using our key land base for investment, should the legislation require that a certain percentage of earnings (i.e. a royalty) be invested back into the province?

- Prioritize social investment in agriculture, farm families and rural communities

- Support social investment in agriculture by restricting farmland ownership to Saskatchewan residents: This recognizes the social value of land. As farm families have demonstrated for generations, social investment in farms and communities (knowing and caring for the land and communities) is neither calculated nor paid in financial capital. The commitment to the farm which farm families demonstrate by dedicating off-farm income and long hours to it adds value, enhances social stability and may improve prospects for entering farmers. Can external capital that removes ownership from the farm operators compensate for this lost social capital? Would lower land prices undermine or enhance farming and the agricultural economy?

- Maximize efforts to build a social economy that values social enterprises: Institute more robust forms of public/collective/social ownership through new forms of land banking, land trusts,

cooperatives and other ownership structures. - Recognize and seek to integrate Indigenous peoples’ relationships to land: Since Indigenous peoples represent an increasing percentage of the population in Saskatchewan, this approach could open the possibility for sharing the land base and using it in ways that respect nature and cultures.

Other policy options that would indirectly affect land investment are regulations restricting the use of farmland to agricultural production only. Another would place a cap on how much land one can own. Also, policy interventions in the land rental market (rent controls) might be considered as more land is farmed through rental arrangements.

Our research indicates that policies that focus primarily on capital investment will only exacerbate the current situation whereby an increasing amount of farmland in Saskatchewan is owned by non-farmers and concentration of land continues to rise. We see much more potential for social and environmental well-being by following a policy direction that emphasizes social investment.

Land policy is critically important in shaping who farms, how farming is done and the fate of rural communities. There is a need to think carefully and collectively about what kinds of farmland ownership legislation we would like to see in Saskatchewan.

This research was made possible with funding from the Canada Research Chair Program.

References

Desmarais, Annette Aurélie, Darrin Qualman, André Magnan and Nettie Wiebe. 2015. “Land grabbing and land concentration: Mapping changing patterns of farmland ownership, in three rural municipalities

in Saskatchewan, Canada,” Canadian Food Studies, Vol. 2, No.1, pp. 16-47. Available at http://canadianfoodstudies.uwaterloo.ca/index.php/cfs/article/view/52

Fairbairn, Madeleine. 2014. “Just another asset class? Neoliberalism, finance and the construction of farmland investment.” In The Neoliberal Regime in the Agri-Food Sector: Crisis, Resilience and Restructuring, edited by Steven A. Wolf and Alessandro Bonanno. New York: Routledge.

FCC (Farm Credit Canada). 2015. Farmland Values Report, 2014. Regina. https://www.fcc-fac.ca/fcc/about-fcc/corporate-profile/reports/farmlandvalues/farmland-values-report-2014.pdf, accessed June 12, 2015.

Annette A. Desmarais

Annette Desmarais is a Canada Research Chair in Human Rights, Social Justice and Food Sovereignty at the University of Manitoba. Her research focuses on food sovereignty—an approach that is gaining momentum internationally. Desmarais was a small-scale farmer in Saskatchewan for 13 years.

Darrin Qualman

André Magnan

André Magnan is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology and Social Studies at the University of Regina. His research examines the history and politics of grain marketing on the Canadian prairies, with a focus on the rise and fall of the Canadian Wheat Board, and the financialization of agrifood systems.

Nettie Wiebe

People who are passionate about public policy know that the Province of Saskatchewan has pioneered some of Canada’s major policy innovations. The two distinguished public servants after whom the school is named, Albert W. Johnson and Thomas K. Shoyama, used their practical and theoretical knowledge to challenge existing policies and practices, as well as to explore new policies and organizational forms. Earning the label, “the Greatest Generation,” they and their colleagues became part of a group of modernizers who saw government as a positive catalyst of change in post-war Canada. They created a legacy of achievement in public administration and professionalism in public service that remains a continuing inspiration for public servants in Saskatchewan and across the country. The Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy is proud to carry on the tradition by educating students interested in and devoted to advancing public value.

View Publication