Finding an Affordable Housing Option: Social Business as the ‘New’ Policy Tool?

Housing affordability is a growing concern in Canada, which is one of the few Western nations that largely depends on market forces to supply its housing stock. It has emerged as a mounting policy issue as federal and provincial governments struggle with addressing the social and economic implications of affordability and the potential consequences of a sharp market correction.

By Kh Md Nahiduzzaman, Assistant Professor, Department of City and Regional Planning, King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals (Saudi Arabia)Housing affordability is a growing concern in Canada, which is one of the few Western nations that largely depends on market forces to supply its housing stock.1 It has emerged as a mounting policy issue as federal and provincial governments struggle with addressing the social and economic implications of affordability and the potential consequences of a sharp market correction.

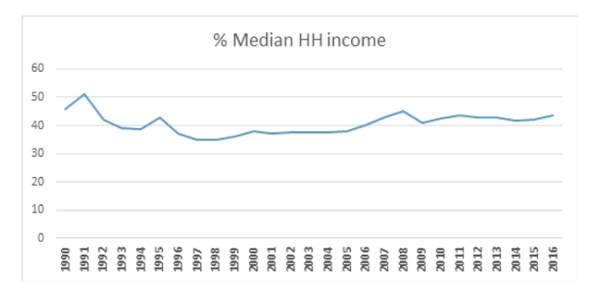

To put the issue in context, about 95 percent of Canadian households obtain their housing on the open market.2 During the post-2008 recession period, housing markets have been relatively strong – spurred by the historically low mortgage interest rates. At the same time, strong demand and constrained supply has significantly increased housing prices, raising affordability challenges for many households. In fact, housing affordability today is worse than at any time since the beginning of the 2000s. In 2011, the Canadians spent more than 40% of their household income on rent and utilities which increased to above 50% in 2015.3

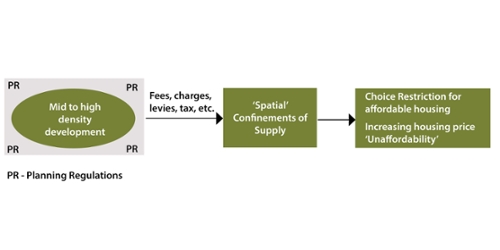

Many factors affect housing affordability in Canada. For example, purchasers of single-detached houses face significant government-imposed costs, including fees, charges, levies and tax. Moreover, under the growing use of densification strategies, urban plans have tended to restrict low-density in favor of medium and high-density housing.5 The result has exacerbated the affordability crisis. In such ‘spatial confinements of supply’, increased demands are accumulated, leading to an overall price hike.

Housing (Un)affordability and Canadian Cities

Across Canada, one in five renters faces an affordable housing crisis, spending more than half their income on shelter. A large portion of the renters pays more than 30 percent of their monthly earnings on housing6, 3:

| Percentage of Renters | Monthly Rent |

| ≥40% | ≥30% of the household income |

| ≥20% | ≥50% of the household income |

Communities facing the greatest housing affordability challenge tend to be the suburbs characterized by soaring home prices, where developers have built little in the way of social housing and rental apartments. About 31 percent of renters in metro Vancouver spend more than half of their salary on housing. Burnaby, Richmond and Coquitlam are among the hardest hit when it comes to housing affordability. In the greater Toronto area, Milton, Witchurch-Stouffville and Vaughan are the suburban communities that have been hit hard by housing unaffordability, with Mississauga having the greatest shortage of affordable rental housing.3 As well, the western Canada resource boom has brought an influx of people into communities in Saskatchewan and Alberta, driving up rents.

Affordable Housing Programs in Canada: a Dependency Path

Since 2011, with CMHC acting as the primary policy instrument, new federal funding for affordable housing has been provided through the initiatives under the Investment in Affordable Housing (IAH) program. During an eight-year period, the federal government has committed to invest $1.9 billion through the IAH. An additional $100 million was invested in new affordable housing in Nunavut between 2013 and 2015.7a As well, the Affordable Housing Initiative (AHI), a multilateral housing framework, has also been agreed to by federal, provincial and territorial housing ministers establishing the broad parameters for bilateral Affordable Housing Program Agreements.7b

Of the $1.6 billion Ottawa annually spends to meet its ‘social’ housing operating agreement commitments, $1.2 billion is cost-shared with the provinces and territories.7b This ‘investment’ significantly subsidizes rents for low-income households, offsets mortgage costs or does both.

Impact of Immigration on Affordability

Another significant factor affecting the housing market is immigration. With an aging population and a declining birthrate, Canada has attempted to address this labor market shortage by attracting skilled immigrants. Historically, Canada has provided rapid responses to refugee crises around the world, the most recent example being the settlement of more than 25,000 Syrian refugees.

Despite the need for skilled labor8, immigrants have been reported to face unemployment and underemployment challenges.9, 10, 11 The average unemployment rate of landed immigrants is 7.6%, with Quebec (9.4%), Nova Scotia (8.9%), and Alberta (8.9%) posting the highest rates.11 Clearly, there is a strong correlation between recent immigrant status and elevated levels of poverty.12 According to the latest Canadian Labor Market report, more than 36% of immigrants who have been in the country for less than five years live in poverty, as opposed to 25% in the 1980s.13 In Toronto alone, the number of immigrant families living in poverty increased 362% between 1980 and 2000, which is far greater than the population growth of 219%.14 The problem is more intense among recent immigrants. Large and medium urban centers, including Toronto, Winnipeg, Quebec City, Regina, Saskatoon and Vancouver, have high concentrations of minority immigrants in neighborhoods experiencing about 40 percent poverty rates.15, 16, 17, 18, 9 Because of the ongoing civil war crisis, most of these immigrants have been Syrian.

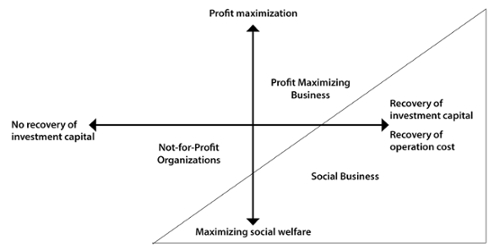

Recently, Boardwalk Rental Communities, a prominent private developer, offered 350 housing units to help resettle Syrian refugees at below market value in Edmonton, Calgary, Fort McMurray, Red Deer, Saskatoon, London, Montreal and Regina.19 The immigrant families will receive a minimum $150 discount on their monthly rent based on a one-year lease. For a conventional housing developer, this is a clear shift of its business principle, from ‘profit maximization’ to ‘non-profit’ or ‘loss-on-the investment’. While this is understood as an expression of corporate social responsibility (CSR), it is perhaps a ‘time-bound’ offer dedicated to a particular population segment.

‘Social Business’ and Housing Affordability

‘Not-for-profit’ or ‘non-profit’ has been a long-established policy approach to solve societal problems. While non-profit organizations do not need to recover operating costs, governments tends to lose their investments, as they subsidize both rent and purchase. It is time to consider a new policy option that bridges public and private interest.

Pioneered by Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus, the ”Social Business” model is a combination of development, economics and human rights. It is as a business not driven by the ‘profit maximizing’ principle, but dedicated to solve long-existing problems. It is based on ‘non-profit’ and ‘non-dividend’ principles – investment remains in the business, while it recovers operating costs (i.e., self-sustainability) and meets its business (social) goals.20 Thus, social business situates between ‘non-profit’ and ‘profit maximizing’ principles:

‘Profit Maximizing’ or ‘Giving Away’ – only Approaches that Work?

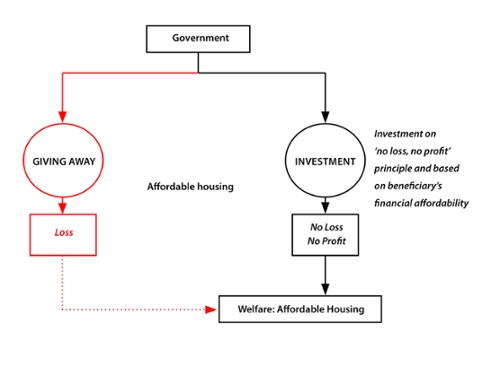

Implicit in ‘social’ or ‘affordable’ housing programs is that government spends on affordable housing programs where return on its capital is not expected. Arguably, government’s ‘giving away’ concept is influenced by a lack of knowledge about the actual financial ability of the intended beneficiaries. Given the current operational principles and existing affordable housing challenges, there is a critical need to re-think how the issue is addressed.

Policy Shift

The social business model builds a mediated ground between ‘profit maximizing’ and ‘giving away’ approaches. Social business would guide the supply of affordable houses to an equilibrium price that the beneficiaries would repay in the form of affordable rent or mortgage. This, in turn, would allow the actors to realize a return on their investment.

Social business can play an important role in guiding the ‘welfare’ mindset into ‘investment’ that would be rooted in the tenant’s actual financial strength. This calls for a review of the construction standard, including design and housing size as per individual’s financial affordability. Clearly, the targeted beneficiaries are perceived to be financially unaffordable against the current housing standard and conventional market price. Thus, ‘affordable design’ could reverse the equation while maintaining a minimum building standard.

Almost all the private developers have CSR-driven financial resources that government or the association of real estate developers could collectively invest based on the social business model. The result would be the construction of affordable houses, with the original investments remaining in the businesses. Moreover, CSR funds could grow as respective real estate developers contribute further, drawing from traditional profitmaximizing businesses. While social business would continue to attract CSR funds, there is a policy need at the federal, provincial and local government tiers to develop specifications for investment. While the benefits of the social business principles in affordable housing policy could significantly improve housing for the less privileged25, 26, its adoption around the world is still evolving. In Scotland, Glasgow is home to about 704 social business-based enterprises, of which 74 are into housing provision. Private developers are taking part in such ‘new’ ventures to initiate another investment route to offer and maximize housing benefits to the residents, while retaining the original capital in the business.27

It’s time for the idea of a public-private partnership in affordable housing business to be re-evaluated. Using the social business model the twin goals of affordable housing and realizing a return on investment can be achieved in a way that meets both public and private interests.

References

1 Scanlon, K. and Whitehead, C. (2004). International trends in housing tenure and mortgage finance, London: Council of Mortgage lenders. www.cml.org.uk

2 Hulchanski, J. D., (2005). Rethinking Canada’s Housing Affordability Challenge, Centre for Urban and Community Studies, University of Toronto

3 McMahon, T. (2015). Affordable housing crisis affects one in five renters in Canada: study [online] Available at: http://www.theglobeandmail.com/real-estate/themarket/affordable-housing-crisis-affects-one-in-five-renters-in-canada-study/article26287843/ (Accessed: November 11, 2016)

4 RBC (2016). RBC Economics: Housing Trends and Affordability, December 2016 [Online] Available at: http://www.rbc.com/economics/economic-reports/pdf/canadian-housing/house-dec2016.pdf (Accessed: March 09, 2017)

5 Canada Home Builders Association (2012). Canadian Housing Industry – Performance and Trends [online] Available at: https://www.nahb.org/~/media/Sites/NAHB/SupportingFiles/3/Can/CanadaPerformanceandTrends2012_20130607021852.ashx?la=en (Accessed: November 10, 2016)

6 Rea W., Yuen J., Engeland J., Figueroa. R. (2008). The dynamics of housing affordability. Perspectives on Labour and Income (Statistics Canada, Catalogue 75-001); 9(1):15-26

7a Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (2016a). Investment in Affordable Housing (IAH) [Online} Available at: https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/en/inpr/afhoce/fuafho/ (Accessed: October 29, 2016)

7b Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (2016b). Affordable Housing Initiative [online] Available at: https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/en/inpr/afhoce/fias/fias_015.cfm (Accessed: November 11, 2016)

8 Reitz, J. (2005). Tapping immigrants’ skills: New directions for Canadian immigration policy in the knowledge economy. Choices, 11(1) (by Institute for Research on Public Policy)

9 Picot, G., & Hou, F. (2014). Immigration, Low Income and Income Inequality in Canada: What’s New in the 2000s? Social Analysis and Modelling Division, Statistics Canada.

10 Weiner, N., (2008). Breaking Down Barriers to Labour Market Integration of Newcomers in Toronto [online] Available at: http://irpp.org/research-studies/choicesvol14-no10/ (Accessed: November 10, 2016)

11 The Canadian Magazine of Immigration (2016) Canada: Immigrants in the Labour Market -March 2016 [online] Available at: http://canadaimmigrants.com/canadaimmigrants-in-the-labour-market-march-2016/ (Accessed: March 8, 2017)

12 Shields, J. (2002). No Safe Haven: Markets, Welfare and Migrants. Paper presented to the Canadian Sociology and Anthropology Association, Congress of the Social Sciences and Humanities, 1 June, Toronto

13 Todd, D. (2013) Growing poverty among Canadian immigrants could explode: Study [online] Available at: http://vancouversun.com/life/growing-poverty-amongcanadian-immigrants-could-explode-study (Accessed: March 9, 2017)

14 Government of Canada (2013). Snapshot of racialized Poverty in Canada, [online] Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/communities/reports/poverty-profile-snapshot.html (Accessed: March 9, 2017)

15 Kazemipur, A., and Halli, S. (2000). The new poverty in Canada. Toronto: Thompson Educational Publishing

16 Galabuzi, G. (2001). Canada’s Creeping Economic Apartheid: The Economic Segregation and Social Marginalisation of Racialised Groups. Toronto: CJS Foundation for Research & Education

17 Picot, G. and Hou, F. (2003). The rise in low-income rates among immigrants in Canada. Ottawa: Statistics Canada

18 Picot, G., Hou, F., and Simon, C. (2007). Chronic Low Income and Low-income Dynamics Among Recent Immigrants. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11F0019MIE2007294, January.

19 Huncar, A. (2015). Boardwalk promises reduced rents for Syrian refugees. CBC News [online] Available at: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/boardwalk-promisesreduced-rents-for-syrian-refugees-1.3323698 (Accessed: November 12, 2016)

20 Yunus, M. and Moingeon, B. (2009). Building social business model: lessons from the Grameen experience. HEC Paris- working paper 913

21 James, A., Leonard, D., Reficco, E. and Wei-Skillern. J. (2005). Corporate Social Entrepreneurship: A New Vision for CSR.” In Epstein, M. and Hanson, K. (eds.) The Accountable Corporation. Vol. 2, Praeger.

22 Yunus, M. (2009). Lecture at RIBA as part of the British Council’s 75th anniversary lecture series ‘Talking without Borders’, 29 May 2009 Available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ti04AOiSHNg&feature=related [Accessed: 8 August 2009]

23 Yunus, M. (2008). Creating a World without Poverty: Social Business and the Future of Capitalism. New York: Public Affairs

24 Nahiduzzaman, K. M. (2012). Housing the Urban Poor: An Integrated Governance Perspective. The Case of Dhaka, Bangladesh, PhD Dissertation, The Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), Sweden

25 Czischke, D., Gruis, V., & Mullins, D. (2012). Conceptualising social enterprise in housing organisations. Housing Studies, 27(4), 418-437.

26 Mullins, D., Czicshke, D., and van Bortel. G., (2012). ‘Exploring the Meaning of Hybridity and Social Enterprise in Housing Organizations’, Housing Studies, 27, 4, 405–17

27 Glasgow Social Enterprise Network (2015). Social Enterprise in Glasgow 2015 [online] Available at: http://www.gsen.org.uk/files/Social-Enterprise-in-Glasgow-2015.pdf (Accessed: March 9, 2017)

Kh Md Nahiduzzaman

Dr. Nahiduzzaman is an urban policy analyst. He is currently working as an assistant professor at the Dept. of City and Regional Planning, King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals (KFUPM), Saudi Arabia. He also held faculty positions at the Dept. of Urban Planning and Environment, the Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), Sweden and Urban and Rural Planning Discipline, Khulna University, Bangladesh. A number of prestigious research grants are credited to his account, notably by Brown University (USA), University of California, Irvine (USA), DfID (UK), British Council (UK), SIDA (Sweden), NSTIP (KSA), KACARE (KSA) and NOMA (Norway). Dr. Nahiduzzaman has been a research fellow at the Watson Institute, Brown University and NIAS (Nordic Institute of Asian Studies), Denmark. He is a member of Western Regional Science Association (USA), Urban Affairs Association (USA), and Association of European Schools of Planning (EU). He is an author of the book “The Regional City: Sustainable Regions and Communities of Place”.

People who are passionate about public policy know that the Province of Saskatchewan has pioneered some of Canada’s major policy innovations. The two distinguished public servants after whom the school is named, Albert W. Johnson and Thomas K. Shoyama, used their practical and theoretical knowledge to challenge existing policies and practices, as well as to explore new policies and organizational forms. Earning the label, “the Greatest Generation,” they and their colleagues became part of a group of modernizers who saw government as a positive catalyst of change in post-war Canada. They created a legacy of achievement in public administration and professionalism in public service that remains a continuing inspiration for public servants in Saskatchewan and across the country. The Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy is proud to carry on the tradition by educating students interested in and devoted to advancing public value.