Freedom from Government: The Origin of Good Ideas

A major preoccupation of people in government is policy innovation. More specifically, it’s how to inject new ideas and ways of doing things that result in policy with innovative and positive outcomes. It’s simple to say, but hard to do.

By Dale Eisler, Senior Policy Fellow, Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public PolicyA major preoccupation of people in government is policy innovation. More specifically, it’s how to inject new ideas and ways of doing things that result in policy with innovative and positive outcomes. It’s simple to say, but hard to do. Just ask anyone who has been in the public service. Chances are they’ve spent hours at retreats, attended brown-bag lunch discussions, listened to armchair conversations and been in breakout groups at forums to discuss the “challenge” of policy innovation. They hear the mantra about the need to be innovative, about “new” ideas and “taking risk”. But inevitably reality gets in the way. They leave the brainstorming session and go back to their cubicle and a work environment where the political and bureaucratic will to risk failure basically doesn’t exist.

It’s not that there are never innovative ideas that come from government. It’s just that people quickly realize that for all the brave talk about policy innovation being crucial, it’s often better that someone else road tests new ideas. Best that policymakers aren’t the first movers and run the risk of being wrong. The result of this systemic sclerosis in government is that good ideas almost always come from outside the insular and risk-averse world of the public sector.

A good example of that innovation is work being done by former Prime Minister Paul Martin. After a career at the pinnacle of Canadian public policy as Finance Minister and then as Prime Minister, Martin now heads the Martin Family Initiative (MFI) out of his office in old Montreal. The primary focus of the effort is to give young Indigenous kids hope and a chance for a good life. Given that half of First Nations children live in poverty and their education attainment rates lag far behind the non-Indigenous population, it’s clearly a laudable initiative. It is also a huge social and economic challenge, one that Martin embraces with singular determination.

Martin’s interest in Indigenous issues reaches far back into his youth. He had summer jobs working in the north, on the shores of Hudson Bay and as a deckhand on a tug barge on the Mackenzie River in the Northwest Territories. His co-workers were all Indigenous. It was a lifechanging experience. To that point he had no contact with Indigenous Canadians or any understanding of their lives. It was a time when he heard firsthand the stories of the challenges young Indigenous men faced and the lack of hope and opportunity that other Canadians take for granted. “The melancholy and sheer unfairness of their lives stayed with me,” Martin says.1

The sensitivity to the challenges faced by Indigenous people fundamentally shaped Martin’s political views. Back in the bleak days of the mid-1990s, when he was Finance Minister, the Government of Canada was mired in an annual operating deficit of more than $42 billion and a federal debt-to-GDP ratio approaching 75 per cent. Fully 36 cents of every tax dollar went to paying interest on the debt. The nation teetered on the financial brink. There was ominous talk of Canada’s debt being reduced to junk bonds and the possibility of the country being bailed out by the International Monetary Fund. In his budget of 1995, Martin famously vowed that the federal deficit would be eliminated “come hell or high water.” Three years later the budget was in surplus without the arrival of either hell, or high water. At least not in a literal sense. But it did come with more than a little pain, especially for the provinces, which had to absorb significant cuts in federal transfer payments.

These days it’s interesting to recall one decision point in Martin’s grim budget. The line Martin refused to cross was spending cuts involving First Nations people. While most departments experienced deep reductions as a result of program review, the then Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development was shielded from cuts. Instead, its annual increase was capped at two per cent. The limit stayed in place after the budget returned to surplus, a lingering restraint that eventually came in for criticism from Indigenous leaders.2 Years later as Prime Minister, Martin put First Nations issues at the centre of his government’s agenda. In fact at his swearing in as PM, he had a smudging ceremony in recognition to his commitment to Indigenous Canadians.

There were two high-profile policy initiatives during Martin’s three years as PM. One was a 10-year health care funding agreement with the provinces, which received significant criticism as merely handing money over to the provinces with no significant strings attached to ensure reform of the system. The other was the Kelowna Accord. It was the culmination of many months of painstaking consultations between the federal, provincial, territorial governments, and leaders of Indigenous groups. The key to getting agreement was the breadth of the consultation. Indigenous leaders from across Canada were not only deeply involved in the negotiations with governments, but took ownership of the outcome. The Accord was a five-year, $5.1 billion agreement that sought to reduce the life gap between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Canadians and finally lift the two-per cent limit on growth in annual funding.3 The $5.1 billion was booked by then Finance Minister Ralph Goodale. But soon after, when the Stephen Harper government was elected, the Accord was cancelled. Arguing the agreement was “written on the back of an envelope”, the money was diverted to other spending. To this day, the process that led to the accord remains a model for consultation with the Indigenous communities, especially given the on-going failures to reach agreement on pipelines and natural resource developments that affect First Nations.

Now, more than a decade later, with Indigenous issues again at the centre of the federal agenda, there are lessons in public policy innovation to be learned from the Martin Family Initiative. Unburdened from the constraints of government, the MFI is breaking new ground that is actually making a measurable difference in the lives of young Indigenous kids. The focus is unequivocally young people, from pre-school to high school, and is evident in the initiative’s simple slogan “It Starts With Kids.”

What’s happening is far removed from policy salons and thinktank panel discussions about policy innovation. It is based on the universally accepted belief that, if you want to give young people a chance at a better life, then give them the opportunity for a good education. Can there be any doubt that the single most important realm of public policy is education? One can debate the details—how much to invest, where to invest, how best to actually deliver education, how to measure outcomes—but no one argues its importance and relevance to social and economic progress. Everyone agrees. As Nelson Mandela famously said: “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.”

Education is Key

Name your policy objective, and chances are education will be a crucial factor in achieving it. The evidence is part of virtually every measurement. Education reduces poverty, increases economic growth, leads to better health outcomes, reduces unemployment, raises standards of living and quality of life, fuels prosperity, and lessens social costs. Education is at the intersection of effective economic and social policy. As the bumper sticker says, “If you think education is expensive, try ignorance.”

It is that belief which underpins the MFI. There are three streams. The first is the “Early Years” which covers pre-natal through to age five. The second is literacy in the initial grades of elementary school. The third is Indigenous youth entrepreneurship and business in high school. To ensure their relevance, applicability and effectiveness, each program is designed working closely with Indigenous people. They are not created and imposed by outsiders, but by people on the ground in the communities.

The Early Years initiative forms the foundation. It comes in two phases. The first provides assistance through “home visitors”, women members of the First Nations communities who are hired to provide support for young mothers. It begins when the women are pregnant and continues until their child reaches age two. The effort is based on scientific recognition that the pre-natal through age five are the crucial years in brain development and determining life outcomes for children. Get the first five years right, and the chances are greatly enhanced the child will do well in life. The second phase focuses on children aged two to the start of kindergarten through the creation of on-reserve child development centres. The centres provide nutritious meals, learning, reading, as well as Indigenous language and culture sessions for the kids.

The literacy program, which starts in Kindergarten, then picks the ball up. It tackles the need to improve the ability of children in the first three grades to read and write. It was first implemented in an Ontario school with a high number of Indigenous children who scored very poorly on literacy levels at the end of Grade Three. The result of the program, which is now in 12 schools, was to not only raise literacy levels of Indigenous kids to the level of other children, but in some cases to surpass it. In Ontario, when the program was introduced, only 13 per cent of Indigenous students met the provincial reading standard. After five years, the level was 81 per cent, well above the provincial average. Writing skill results were even better. They rose from 33 per cent of grade three students meeting the provincial standard, to 91 per cent, significantly higher than the 78 per cent provincial average.4

The final piece was development of the pedagogy and textbook by Indigenous teachers for an Indigenous youth entrepreneurship course in high school for grades 11 and 12. While most high schools have a business class elective, none had one that addressed Indigenous business education. The class was introduced in a Thunder Bay high school and now is in 40 high schools across Canada, including 11 in Saskatchewan. The 2017-18 average success rate for enrollment and completion of the class in Saskatchewan schools was more than 81 per cent.

Coupled with the specific classroom education initiatives, is a First Nations’ Schools Principals’ Course to assist on-reserve school principals who lack resources, support and learning opportunities. The principals program, which was developed by 20 leaders from First Nations schools, gives principals the network, learning and support system they lack and need to be successful.

In each case, the programs are pilot tested for five years to determine success. The five-year process is fully funded by the MFI, with support of other non-government donors. Once proof of concept is secured, and relevant data produced, the road-tested program is then turned over to Indigenous communities for implementation, with support from willing governments. There is virtually no chance that government could follow the same path of innovation. The fact is government has little capacity or opportunity to pilot test policy, because by definition it means risking taxpayers’ dollars on special treatment that could ultimately fail.

The Martin Foundation is not alone in its efforts to develop, test and implement innovative policy. In Regina, the Mother Teresa Middle School, which was started by businessman Paul Hill, focuses its efforts on vulnerable and economically disadvantaged youth in Grade 6-8. It provides extended school time, small class and school size, transitional supports by “an innovative, extensive middle year’s program”, all based on the Jesuit education model. As students are drawn from disadvantaged neighbourhoods, the majority of students at Mother Teresa are of Indigenous ancestry.

The Cost Factor

The inevitable question that arises for government policymakers is cost. Virtually any issue can be addressed and hopefully resolved, or at least mitigated, with enough public funding. But the more pertinent question is can Canada afford not to follow the path set out by Martin and others. In its study “The Contribution of Aboriginal People to Future Labour Force Growth in Canada”, the Centre for the Study of Living Standards last year examined how to close the socioeconomic gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians.

It had two key findings. One was that the Indigenous population is growing much faster than non-Indigenous, particularly the younger aged cohort. The other was that future labour force growth would be driven by Indigenous people, 83 per cent in the three territories, 72 per cent in Saskatchewan and 52 per cent in Manitoba. When you couple that with much lower labour force participation rates and poorer educational outcomes for Indigenous Canadians, the implications become obvious for the Canadian economy.5

One of the authors of the study was Don Drummond, former associate deputy minister of finance with the federal government and senior VP and chief economist for TD Bank. In 2013, Drummond co-authored another study with Ellen Kachuck Rosenbluth. Entitled “The Debate on First Nations Education Funding: Mind the Gap”, it concluded that First Nations schools on average were getting 30 per cent less funding than what provincial public schools were receiving. The study’s impetus was the widely held recognition that education is critical to better life outcomes for First Nations people. The context was that in 2011 the high school graduation rate on reserve was 35.3 per cent compared to 78 per cent for the total Canadian population.6

However, there are those, such as John Richards and Barry Anderson, who dispute the funding gap argument. Richards and Anderson maintain it is difficult, if not impossible, to measure First Nations’ school funding against provincial schools. They argue that First Nations schools often have a small number of students —sometimes less than 50—and there are few provincial schools to use as comparators because smaller schools have been closed or amalgamated for economies of scale. “In some cases, the gap (however defined) is undeniably large. On the other hand, in some cases INAC funding probably exceeds provincial funding,” they argue.7

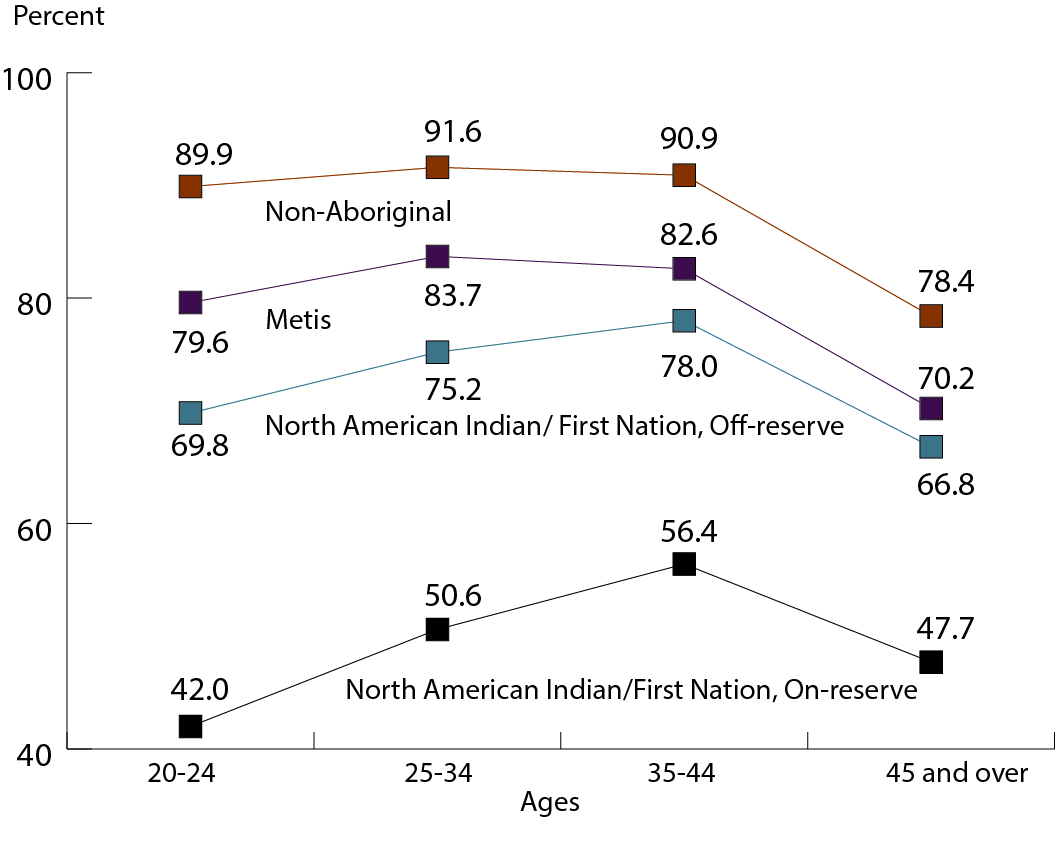

Where there is no disagreement is that outcomes for First Nations students attending on-reserve schools lag those of other students. While attainment levels for Indigenous students attending non-First Nations schools are better, they still are below those of non-Indigenous students.8

Figure 2: High School Certification or Above

It is those two realities that form the rationale and motivation behind Martin’s initiative to tackle issues head-on. The scope of the approach, from pre-natal through to Grade Three, and the Indigenous entrepreneurship course for high school students, directly supports the universal belief that education is the most powerful public policy tool at the disposal of governments. The constraint is that the solution will be costly if governments are to act in a serious and focused manner. To that, Martin argues the alternatives will be far more costly, in financial and human terms. “I don’t know of anyone, unless they were a direct descendant of British aristocracy, who would be a success today if someone hadn’t invented publicly funded quality public schools for everyone,” Martin says.

The Path Forward

Canada’s aging demographics clearly point to the right policy path forward. For the first time, Canada now has more people aged 65 and higher than those less than age 15. Of those under 15, the fastest growing segment is Indigenous kids. Over the next two decades the labour market will be driven largely by growth in the proportion of Indigenous Canadians of working age. Projections are the percentage of Indigenous people of working age will grow from its current level of 3.5 per cent to 5.6 per cent. But within those numbers are two other critical facts. One is the labour force participation rate of Indigenous people in 2011 was five percentage points below the non-indigenous population. The other is the gap for the 15-24 age group was 12.4 percentage points below the non-Indigenous participation rate.9

The policy challenge is obvious. The key to economic growth and better social outcomes is closing the socio-economic gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians. The route to achieve that is through education. If history has been any lesson, not taking the steps necessary to give Indigenous children an equal chance to succeed, especially in their childhood, would be continuing a policy failure of immense proportions. Call it policy innovation if you like. But another description is common sense, and like many good ideas, it comes from outside of government.

References

1 Interview, Aug. 28, 2018

2 p.112, Budget Plan, Department of Finance, 1995

3 (http://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/clearing-the-air/alcantaraspicer/)

4 p.16, It Starts With Kids, Progress Report 2018, MAI

5 http://www.csls.ca/reports/csls2017-07.pdf

6 p. 2, The Debate on First Nations Education Funding: Mind the Gap, Don Drummond and Ellen Kachuck Rosenbluth, Queen’s University, 2013.

7 p. 12, Students in Jeopardy: An Agenda for Improving Results in Bandoperated School, Anderson and Richards, C.D. Howe Commentary No. 444, January 2016

8 A Few Census 2016 Aboriginal Education Results, John Richards

9 http://www.csls.ca/reports/csls2017-07.pdf

ISSN 2369-0224 (Print) ISSN 2369-0232 (Online)

Dale Eisler