Have we hit “peak globalization”?

As we mark the 75th anniversary of the Bretton Woods conference, which under American, British and Canadian leadership established the postwar international architecture of a rules-based global trading system and the institutions to support it (IMF, World Bank, WTO, parts of the UN), it is timely to ask a critical question. Specifically, whether the astounding growth in globalization Bretton Woods nurtured and supported has reached its peak and, if so, what might be the implications.

By Kevin Lynch, Vice-Chair BMO Financial, former Clerk of the Privy CouncilAs we mark the 75th anniversary of the Bretton Woods conference, which under American, British and Canadian leadership established the postwar international architecture of a rules-based global trading system and the institutions to support it (IMF, World Bank, WTO, parts of the UN), it is timely to ask a critical question. Specifically, whether the astounding growth in globalization Bretton Woods nurtured and supported has reached its peak and, if so, what might be the implications.

There is no question that trade liberalization, coupled with the financial architecture to reinforce it, spurred a post Second World War period of unprecedented growth and stability. But political and economic dynamics are shifting. National boundaries are becoming less open, bringing inevitable economic and social consequences. Whether it’s the United States in the age of Donald Trump, or the rise of domestic populism in Europe, times are changing. The issue is whether this is a temporary phase, or a more fundamental adjustment to a new world order.

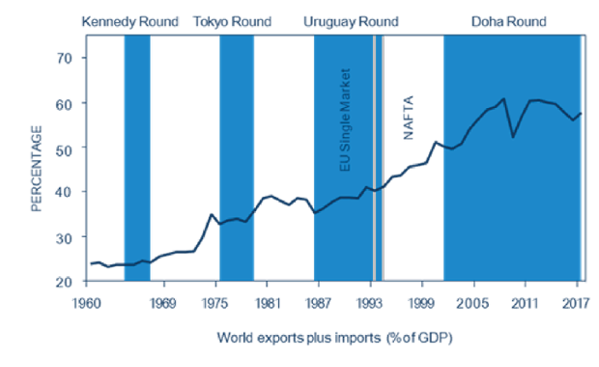

Not surprisingly, there are a number of ways to measure globalization—trade intensity, cross-border financial flows, international reserves, human migration and even tourism flows. Each points to globalization plateauing and retrenching, with the one exception of cross border people flows (migration and tourism). Figure 1 shows the progression of the most commonly used measure of globalization, global trade intensity (calculated as the sum of global exports plus imports as a percentage of global GDP), from 1960 to today. It contains several important messages that are fundamental to the question of whether globalization has reached its limits and is beginning to recede.

First, trade agreements matter to globalization, and the failure of the Doha Round mattered greatly in that it signaled a stalling of the postwar trend of liberalizing trade practices and tariffs; second, trade intensity growth halted with the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008-09 and has not resumed growing despite a near decade long recovery; third, global supply chains have played a critical role in pulling emerging economies into global trade over the last two-and-a-half decades, but they too are peaking as corporate risk management in the face of global trade and technology tensions is reshaping supply chains; fourth, trade in services, although still only 25 per cent of global trade, has been growing much more rapidly than goods trade, but faces the dual risks of less well-articulated trade rules for services combined with diverging national regulatory treatments of digital commerce; and fifth, recent U.S. tariff increases and US-China trade tensions, as well as an ageing and slowing global expansion, are not yet reflected in this data, only further reinforcing the notion that global trade intensity has not only peaked but may be in retreat.

Figure 1: Global Trade Volume as a Percentage of GDP, 1960-2016

Besides trade in goods and services, global financial integration is measured by cross-border financial flows. These also peaked at the onset of the global financial crisis and have been in retreat since then, led by the OECD economies. Interestingly, China has actually increased its global financial exposure, the only major economy to do so. International reserves, another perspective on financial globalization, peaked in 2010 at $12 trillion (USD) as the global financial crisis began to unwind, and have been roughly constant since then.

The exception to these economic measures of globalization, all of which indicate that globalization has peaked, is crossborder people flows, which continue to grow. The annual flow of documented migrants has risen from 150 million in 1990 to 250 million in 2017, which itself is generating a populist backlash to globalization in the United States and many European countries. Over this same period, international tourism flows have more than doubled to 1.2 billion people in 2016, with China the largest source of growth in recent years.

What are the consequences?

So, since it appears we have hit “peak globalization”, what are the consequences? Several interesting correlations are emerging.

For example, over the last decade, while globalization was stalling, so too did per capita growth in global GDP, which fell by almost 50 per cent to 2.3 per cent per year on average, from an average of 4.2 per cent over the 1990 to 2007 period. And this growth decline was most pronounced in OECD countries. The retreat of globalization is also strongly correlated with a significant decline in productivity growth in OECD economies over the last decade. Both are suggestive of the fact that globalization is positive for both productivity growth and income growth in Western economies. And yet, the rise of populism and the political push back against globalization have been most prominent in these same Western economies, particularly the United States.

Another striking outcome is that, while globalization has reduced inequality between countries, it has been accompanied by increased inequality within countries, and this is true in both advanced and developing economies. This later development has stoked populism and protectionism in Western countries such as the U.S. where middle-income workers with middling education and skills have been hollowed out, driving increases in inequality. Populists have placed the blame squarely on “unfair foreign competition”, “bad trade deals” and immigrants “stealing jobs”. The reality is much more complex. It includes technological change replacing workers; under investment in education and skills training reducing employability; ageing demographics, requiring immigrants for labour force growth; and, competitiveness diminished by an unlevel playing field of trade rules, with China cited as a major culprit.

There is a surprising paradox in all this. It is that while globalization has made the world vastly more interconnected in terms of supply chains, finance, technology, trade, data and people flows, it has at the same time led to a world that is more multipolar and more decentralized than it was several decades ago, particularly with the “rise of the rest” in Fareed Zakaria’s evocative term. And this development has profound geopolitical ramifications.

Over the postwar arc of globalization we see in Figure 1, geopolitical power and influence have shifted enormously, reflected in the changing fault lines. We have moved from a G5/G7 world in the 1970s and 1980s, with Russia in military and ideological opposition to Western nations, to a U.S.-led G1 world with the collapse of the USSR in 1989-90 and the ascendency of Western liberalism and capitalism. Then came the G20 world in 2008 where collective management of the fallout from the global financial crisis was needed in a highly interconnected world, to a G2 world today where the U.S. and China are competing centres of global economic, geopolitical and military power.

Indeed, US-China tensions are likely to be quite different from the US-USSR cold war, as China, unlike Russia, is an economic power as well as emerging military power, with a newly assertive global geopolitical agenda. The U.S. increasingly sees China as a strategic competitor, especially in technology. China sees the U.S. as a blocker, impeding its rightful economic and political return to global influence. As Graham Allison has written, these are the historic conditions for long term tensions punctuated by short term truces. And, just as in the previous US-USSR rivalry, but in different ways such as the possibility of a US-China “tech cold war”, this can lead to pressures on other countries to “align” with one or the other great power, creating another source of deglobalization.

As we move forward, globalization will also continue to confront new waves of disruption generated by technological change, creating both opportunities and risks. This fourth Industrial Revolution is upending how to create competitive advantage within and across countries, as well as disrupting long-accepted corporate models and business sectors, with finance, retail, communications, hotels and transport as prime examples. On the trade front, digital trade including e-commerce—the Amazon world—is a possible game-changer to globalization, with the potential to propel services trade to par with goods trade. But here the risk is not looming regulation but diverging digital and data regulations and standards across major economic regions. These factors risk creating “digital regulatory blocs” (e.g. E.U., U.S., China), imposing new impediments to global growth in digital services trade.

In spite of the forces of de-globalization, the ideas and goals of the Bretton Woods founders have much relevance for today. Their generation, having come through two wars, saw global trade as a way of connecting countries and creating a shared stake in prosperity. Having experienced the downsides of great power politics, they opted for the “power of rules” over the “rule of power”, establishing multilateral rules governing trade and the institutions to support it. Realizing that nationalism is nurtured by disaffected populations, they invested in development as a complement to trade, and encouraged flows of capital and people as well as goods.

Worryingly, the lessons of Bretton Woods are under attack by one of its chief architects, the United States. Bilateralism over multilateralism, power over rules, unilateralism over alliances, walls over bridges, abandoning international systems rather than fixing them—these policy directions not only affect globalization but also national prosperity everywhere as well as global stability. IMF modelling of the effects of possible US-China tariff wars are sobering, and the impacts are felt, and often amplified, well beyond these two economies.

What should be the response?

How should Canadian firms and Canadian policy makers respond to “peak globalization”? It certainly complicates the existing imperative of diversifying our trade, which is currently heavily over-weighted with the United States (75 per cent), a market that is not as open or certain under the proposed new NAFTA as it once was. But it should also be a clarion call to up our trade game—we are neither the trading nation nor the nation of traders that we can be and should be.

For Canadian business, it points to a significant ramping up of corporate efforts to better understand and take greater advantage of the new CETA and TPP11 trade agreements, which provide rules-based windows for both goods and services to Europe and parts of Asia. The fact that the United States is not a signatory of either agreement creates an opportunity for Canada to become a larger trans-Atlantic and trans-Pacific hub when combined with the access provided to the U.S. market by the current and proposed NAFTA arrangements.

It also suggests defensive strategies will be needed in the event of an expanded US-China trade conflict which would have negative spillover effects on Canada and Canadian growth prospects. While not easy to do, it means we need to grow in new markets and take market share in existing markets by becoming more competitive. And this is where our existing competitiveness weaknesses in innovation, productivity, regulatory burden, strategic infrastructure and business investment come to the fore, and must be tackled.

One example of these competitiveness challenges is the state of our export infrastructure. How well would Canada score on a global trade infrastructure benchmarking survey with questions such as: Oil and gas pipelines to west and east coasts for export? LNG export facilities? World-class ports superior to anything on the American east or west coasts? State of the art logistics capacity to anchor Canada as a global trade hub? Leading digital, data and AI capacities to facilitate seamless end-to-end trade in goods and services? Products, services and companies with global brands? The answer is that we have to think and act more like Singapore, a country with far fewer advantages but with a much greater focus on what it takes to be globally competitive.

More than 15 years ago, the federal government embarked on a “gateway” strategy to upgrade our export infrastructure capabilities on our east and west coasts as well as on the Canada-US border. It would be timely to consider implementing a next-generation gateway strategy to facilitate trade diversification at scale.

Trade travels along sectoral pathways, and we need to reinforce our sectoral trade strategies and trade competencies if we are to break into new markets, particularly CETA and TPP11, at scale rather than incrementally. We have to get better at branding Canadian products and services in foreign markets and much better at engaging SMEs in cross border trade. Both require new approaches for a new global reality.

The digital data revolution will soon transform trade just as it is now disrupting all sectors of the domestic economy and society. Canada has to decide whether to embrace being a leader or accept being a laggard in digital trade—there is no middle ground given the speed, scale, and scope of technological change today. With global top 30 innovation ecosystems in Toronto-Waterloo, Vancouver and Montreal, and emerging ecosystems in Ottawa, Halifax and Saskatoon-Regina, there is considerable innovation capacity and talent in Canada to draw upon. But currently, American and Chinese firms dominate info tech, and will threaten to do the same for digital trade, unless firms in other countries such as Canada attempt to stake out an international presence in digital services.

More broadly for Canada, it highlights the need for national trade strategies designed for a world of peak globalization and possible long-term US-China trade tensions. These could build on the work of the federal government’s Growth Council and Economic Strategy Tables among others, engaging the business community as well as federal and provincial governments in a collective approach to the way forward on trade diversification, much as was done to take advantage of the FTA in 1988. They should involve provincial and territorial governments in both the development and execution of trade strategies designed for an era of peak globalization. And, in the coming federal election, trade policy and Canada’s place in a world undergoing major shifts should be part of the national debate.

Canada has strengths in many sectors, ranging from natural resources to agriculture to seafood to education to tourism to finance to clean technologies to name a few. But we underleverage these strengths by underinvesting in innovation and leading-edge technologies which is what our foreign competition is doing. Our trade penetration into Asian and European markets is low today compared to other G7 countries, and peak globalization and technological disruption will make the going even more challenging unless we make a collective effort to seriously up our trade and competitiveness game. The prospective gains in terms of growth, jobs and income are well worth the effort.

The Honourable Kevin Lynch, P.C., O.C., PH. D, LL.D

The Honourable Kevin Lynch has been Vice Chairman of BMO Financial Group since 2010. Prior to that, he was a distinguished former public servant with 33 years of service with the Government of Canada, serving as Clerk of the Privy Council, Secretary to the Cabinet, Deputy Minister of Finance, Deputy Minister of Industry, as well as Executive Director for Canada at the International Monetary Fund.

Kevin is the past Chancellor of the University of King’s College, the past Chair of the Board of Governors of the University of Waterloo, a Senior Fellow of Massey College and a Trustee of the Killam Trusts. Since retiring from government, he has written over 140 policy op-eds and articles, and speaks frequently at conferences in Canada and abroad.

Kevin earned his BA from Mount Allison University, a Masters in Economics from the University of Manchester and a doctorate in Economics from McMaster University. He was made a Member of the Queen’s Privy Council for Canada in 2009, was appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada in 2011, has received 11 honorary doctorates from Canadian Universities and was awarded the Queen’s Golden and Diamond Jubilee Medals for public service.