Income inequality and the rise of U.S. populism: A cautionary tale for Canada

The evidence shows the crux of the problem has been the decoupling of productivity growth from incomes. The reasons are many, inter-related and in many cases irreversible. The advent of globalization and free trade has brought both benefits – lower cost for imported goods, expanded market opportunities – and costs – loss of jobs, downward pressure on the value of labour, the decline of organized labour. At the same time, free trade has limited the capacity of governments to intervene in markets and global capital flows have increased the economic and political power of corporations.

By Dale Eisler, Senior Policy FellowThe spectacle of the United States presidential nomination process has created an avalanche of reactions, and more than a little soul searching. Chief among them has been to ask how, on earth, did it come to this? While people are searching their souls, they might also consider whether this is also a cautionary tale with lessons for Canadian policy makers.

In early days, the presidential nomination races were both a novelty and a curiosity. Donald Trump was the novelty. A bombastic, egotistical real estate developer and reality TV personality, the showman Trump was thought an unserious candidate, but entertaining in a narcissistic sort of way.

The curiosity was Bernie Sanders. An avowed democratic socialist from Vermont, Sanders was considered a distraction, too far left to be considered a real threat to Hillary Clinton’s ascension to the Democratic nomination.

The conventional wisdom was the two would flame out quickly. Then Trump and Sanders each won their parties’ respective New Hampshire primaries, after both came within a hair on winning the Iowa caucuses. Each was drawing huge, animated crowds. Sanders talked about income inequality, a disappearing middle class, a corrupt democracy controlled by the one-tenth of one percent who held more wealth than the bottom 90 percent. He said it was time for a political revolution.

Trump bragged about his wealth, how he couldn’t be bought, how illegal immigrants were stealing the jobs of real Americans, how he would make America great again, starting by building a wall along the Mexican border, deporting 11 million illegal immigrants and banning Muslims from entering the U.S. He took particular delight in being unabashedly politically incorrect. The crowds loved it.

Instead of self-destructing, Trump gained momentum and became the clear Republican favourite. Sanders faded somewhat in the face of the Hillary Clinton juggernaut, but remained a clear threat, attracting massive crowds drawn to his message of income inequality. Both are anti-establishment voices.

Gradually, the novelty and curiosity wore off and morphed into concern, then outright panic. The Republican establishment became apoplectic that a “con man” and loudmouth like Trump was marching to the nomination. It was nothing less than a hostile takeover of the Republican Party by a “phony” who wasn’t even a conservative. Worse, if Trump succeeded, the Democrats would almost certainly win the presidency.

As for establishment Democrats, the reaction to Sanders - if only because he seemed less an existential threat to the party bigwigs clustered around the favoured Clinton - was more measured. Clinton simply appropriated much of Sanders’ rhetoric about income inequality, the demise of the middle class and the evils of Wall Street bankers.

For all their differences, Trump and Sanders tapped into the same vein of anger and frustration. At its core is a belief that ordinary people are losing out, that the American dream, based on the belief that if you work hard you’ll be rewarded and get ahead, no longer exists. Most disturbing has been Trump’s fear-and-loathing rhetoric, which has inflamed tensions and led to violent clashes at his rallies.

Stripped to its essential ingredient, this populist uprising is rooted in the reality of income inequality and a disappearing middle class. The truth of income inequality in the U.S. is palpable. For Sanders it’s evidence the system is rigged against ordinary working people. For Trump, it’s evidence of politicians being bought and sold by special interests. For many Americans it’s the evidence of their lives, made worse by the recession of 2008 when millions lost their homes while the big banks got bailed out and CEOs made off like bandits.

So, aside from its perverse entertainment value for Canadians watching from a distance, how is this rise of raw and at times rank U.S. populism relevant to Canada? Actually, perhaps more than you might think. It’s not as if we didn’t see our own mini-version with the spectacle of former Toronto mayor Rob Ford.

Income inequality and Canada

At the recent Public Policy Forum Atlantic Awards event in Halifax, recipient Peter Nicholson called the issue of income inequality “a public policy conundrum for the ages.” Nicholson, past president of the Council of Canadian Academies and senior policy adviser to former Prime Minister Paul Martin, said that of all the policy issues facing governments, one of the most challenging for many mature economies “is the intensification of income inequality and its implications for the social contract on which prosperity and democracy ultimately depend.”

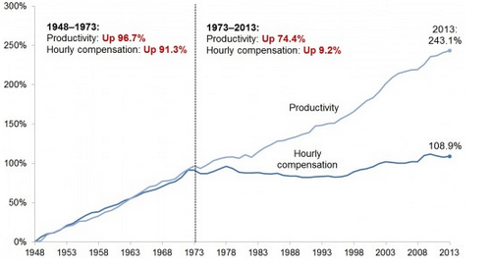

The crux of the issue has been the decoupling of productivity growth from incomes. In economic terms, the traditional social contract is built on the notion that when an economy is growing and labour productivity rising, incomes will rise as well. As the chart below shows, that was the case in the U.S. from the late 1940s to the early 1970s – productivity and incomes grew at almost an identical pace. But for the last 45 years, incomes have grown by only 9.2 per cent, while productivity has risen 74.4 per cent.

In Canada, we avoided much of the pain and suffering experienced by Americans in the 2008 Great Recession. Our stronger, better-regulated banking sector did not lead to a U.S.-style financial crisis and housing meltdown. Our recession was more manageable. The middle class did not get crushed like in the U.S., where people’s equity vanished, along with their jobs.

But that was then. This is now: Canadians household debt is higher than it was in the U.S. in 2008 when maxed out consumers hit the wall. Now, Canadians are mortgaged to the hilt. Now, Canada’s economy limps along at a pace far slower than the U.S. Now Canada’s unemployment rate is a stubbornly high 7.3 per cent, while the U.S. is approximately five per cent and our productivity continues its decades long lag of the U.S.

During what has been an extended period of extraordinarily low interest rates, Canadians have shielded themselves from an underperforming economy and flat income growth by taking on record debt levels. As well, the impact of globalization, which has undermined incomes and hollowed out the manufacturing sector, has been softened by what, until recently, were a very strong commodity sector and a strong real estate market, where home equity values were rising.

As well, the LICO (Low Income Cut Off), or poverty rate, in Canada has declined in recent years. LICO is the income threshold below which a family will likely devote a larger share of its income on the necessities of food, shelter and clothing than the average family. After peaking at more than 15 per cent in 1995, the poverty rate has steadily fallen by a third to less than 10 per cent.

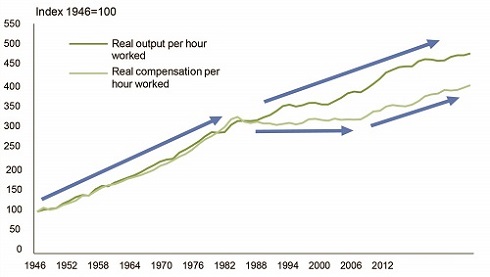

But what do overall income trends tell us? Not unlike the U.S., we have seen Canadian income growth lag behind the rate of increases in productivity. The break point occurred in the early 1980s when productivity continued to rise, but incomes did not. For the decade from the mid-1990s to mid-2000s, income growth stalled before beginning to rise with productivity near the end of the last decade, in part due to personal tax cuts.

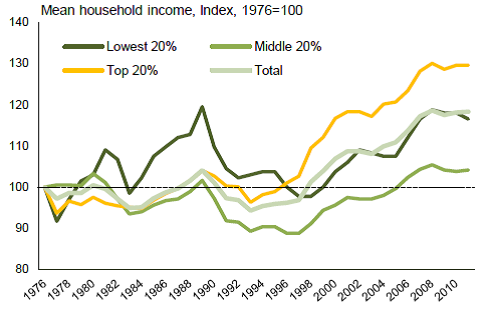

From the early-1990s onward, the average after-tax income of the top 20 per cent of income earners has increased by almost 40 per cent, while the middle 60 per cent of income earners and the bottom 20 per cent have witnessed very little, or no growth in their incomes. The 1990s were a period when the income inequality gap widened, in part due to cuts in transfer payments by the federal government to deal with a growing fiscal deficit.

The chart below shows the widening gap between the top 20 per cent of income earners and the middle 20 per cent. In constant dollars from a starting point in 1976, the middle 20 per cent saw their average real income actually decline through the 1990s, only to grow slightly in the first decade of 2000. At the same time, the top 20 per cent have seen a steady increase in their incomes, starting in the mid-1990s.

Conclusion

So, back to Nicholson’s assertion that income inequality is a “public policy conundrum for the ages.” What’s to be done?

The evidence shows the crux of the problem has been the decoupling of productivity growth from incomes. The reasons are many, inter-related and in many cases irreversible. The advent of globalization and free trade has brought both benefits – lower cost for imported goods, expanded market opportunities – and costs – loss of jobs, downward pressure on the value of labour, the decline of organized labour. At the same time, free trade has limited the capacity of governments to intervene in markets and global capital flows have increased the economic and political power of corporations.

There can be no turning back the clock, nor should we want to, given the benefits the global economy have had in lifting hundreds of millions of people in the developing world out of poverty3. But it is this transfer of wealth from the rich, developed world like the U.S. and Canada to much poorer populations like those in Asia that reflect today’s reality of income inequality in North America.

Clearly, there is no easy solution. But the first step is recognizing that stagnant incomes are the problem. When people feel they are working harder and not being rewarded, it is a recipe for populist discontent. Fairer tax policy can be part of the answer. That means higher taxes on the wealthy and reduced taxes for middle- and lower-income earners. It also means investments by the private and public sectors in research, development, innovation and education. But most of all, it also means restoring the social contract, the implicit agreement that all members of society cooperate for the benefit of all, and upon which, in the words of Nicholson, “prosperity and democracy ultimately depend.”4.

Notes

1. TD Economics, The Case for Leaning Against Income Inequality in Canada, Nov. 24, 2014

2. p. 4 Peter Harrison, Median Wages and Productivity Growth in Canada and the United States, Centre for the Study of Living Standards, July 2009

3. The Economist, June 1, 2013, The global poverty rate has been cut in half in the last 20 years

4. Peter J. Nicholson, Marching Toward the Sound of Gunfire, Remarks to the Public Policy Forum Awards Dinner, Halifax, N.S., March 3, 2016

Dale Eisler

Dale Eisler has an extensive background in the federal public service and Canadian journalism. After a 25-year career in journalism with Saskatchewan and national publications, Dale spent 15 years in various senior roles with the Government of Canada, most recently as Assistant Deputy Minister for the Energy Security Task Force at Natural Resources Canada. Prior to that he spent four years serving as Canada’s Consul General in Denver, CO . Before his posting in the U.S., Dale was Assistant Secretary to the federal cabinet for Communications in the Privy Council Office and began his role in Ottawa as Assistant Deputy Minister for Communications in the Finance Department. He received the 2013 Joan Atkinson Federal Public Service Award of Excellence. He is the author of three book, including “False Expectations, Politics and the Pursuit of the Saskatchewan Myth” and, most recently in 2010, the historical fiction novel “Anton, a young boy, his friend and the Russian Revolution.”

People who are passionate about public policy know that the Province of Saskatchewan has pioneered some of Canada’s major policy innovations. The two distinguished public servants after whom the school is named, Albert W. Johnson and Thomas K. Shoyama, used their practical and theoretical knowledge to challenge existing policies and practices, as well as to explore new policies and organizational forms. Earning the label, “the Greatest Generation,” they and their colleagues became part of a group of modernizers who saw government as a positive catalyst of change in post-war Canada. They created a legacy of achievement in public administration and professionalism in public service that remains a continuing inspiration for public servants in Saskatchewan and across the country. The Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy is proud to carry on the tradition by educating students interested in and devoted to advancing public value.