Making Co-Management Work: A Primer

Beyond policy is implementation. Too often what people believe to be good policy fails not because the policy itself is misguided, but because its application is flawed by lack of planning, organization and execution. This Policy Brief takes a different approach.

By Sujata Manandhar, Post-doctoral fellow, University of Saskatchewan and Yukon University; Nadia Joe, Environmental Scientist, Green Raven Environmental Inc.; and Douglas A. Clark, Associate Professor, USask School of Environment and SustainabilityBeyond policy is implementation. Too often what people believe to be good policy fails not because the policy itself is misguided, but because its application is flawed by lack of planning, organization and execution. This Policy Brief takes a different approach. Rather than focus on policy, it seeks to serve as a real-world practical guide for new people entering into existing or new co-management regimes that draws upon experiences from across the Yukon and research elsewhere. It describes what they need to know and do to make co-management work well. It is written for northern Canadian Indigenous communities and their partners, but is relevant as well to many other collaborative governance situations. The settlement of Indigenous Land Claims in the north created many new co-management bodies, and this document is both based on and intended to support their ongoing efforts. This guide is organized into four sections: defining co-management, preparing to be involved in it, actually implementing it, and some critical lessons others have learned.

While, each of the authors has dedicated considerable time reviewing (and contributing to) the literature on co-management, the lessons in this primer have largely come from our ongoing collective experience. We plan, we practice, and we fail. We discuss, we document our learnings, we try again and, sometimes, we encounter a success.

Each co-management process is created within a unique set of conditions and there is no “one size fits all” solution to making co-management work. We have identified, through careful observation and rigorous documentation, a set of lessons to help guide you down an ‘easier’ path. While you may find, like us, there is no ‘easy’ path towards co-management, we hope you find it a rewarding path and that you may adjust your expectations for the length of the journey.

What is Co-Management?

Most definitions for co-management are deceptively simple, but putting them into practice takes time, effort, resources, and patience.

“Co-management is a partnership arrangement in which the community of local resource users, government, other stakeholders and external agents share the responsibility and authority for decision making over the management of natural resources.” (Pomeroy & Rivera-Guieb, 2006)

“Co-management is a relationship that involves a change from a system of centralized authority and top-down decisions, to a system which integrates local and state level management in arrangements of shared authority, or at least shared decision-making.” (Rusnak, 1997)

Preparing for Co-Management

Do your homework. Understand traditional management systems such as clan systems, wampum belt and hereditary leadership in the place you are in. Co-management systems need to be supported by, and work with, those traditional approaches, including appropriate ceremonies and leadership roles. Gather as much existing information and as many tools as possible to understand the ecological and socio-economic issues, as well as descriptions and delimitations of territories, sites, or natural resources of interest. Do not overlook previous traditional use studies, recorded oral histories or living knowledge keepers.

Communicate. Co-management participants should be united and promote their common vision. This requires engaging citizens and their governments’ staff, industrial partners and their staff, and other involved stakeholders before entering into co-management arrangements. Make co-management partners clear about communities’ needs, interests, priorities, and individual’s roles and responsibilities. A citizen-focused communication strategy is necessary, along with the people and funds to carry it out across multiple levels.

Organize. Link together co-management activities, people, and goals. Strategize and set out priorities that will meet both the community’s and organization’s shared interests and needs. Governmental or organizational leads, Indigenous leaders, and all their representatives should be well-informed, organized, and supported by a team dedicated to the task. Ensure there is adequate financial support for all parties to participate (including meetings, independent facilitation, and technical discussions). It is important to maintain and even expand opportunities to secure necessary resources in the later stages if needed. That can come through negotiation, revenue-sharing, or other ways.

Any negotiations (e.g. between Indigenous communities/governments, other governments, and/or industry) need enough time to build relationships and explore shared interests. As much as possible, co-management should not be done under time pressures. Co-management agreements should enable a longer-term common vision of desired futures based on all the best available knowledge rather than being constrained by a pre-determined, and often technical, set of options. Parties should be aware of and understand the rules and procedures of negotiations before agreeing to them. Community teams need to include their knowledge-holders and cultural advisors. There should be independent, and trusted, professional support and cultural advisors on hand to facilitate the process and help to navigate through conflicts.

Build capacity. Recognize what limitations exist within the co-management partners at the outset and work together to close those gaps. Arrange a team (full time staff and additional co-ordination assistant(s)) dedicated solely to co-management processes. Analyze and prioritize administrative needs realistically, which will help to allocate the necessary economic and human resources to complete work efficiently. Promoting and supporting the co-management process requires a mix of traditional local knowledge as well as technical knowledge in fields such as ecology, social science, economics, engineering as well as project management and “people skills”; especially for working across cultures. Such teams need energy, passion, willingness, creativity, dedication, and continuity.

Be prepared for the long haul. It is easy to underestimate how much time and sustained effort will be needed. Achieving concrete results in a short period of time is rarely possible given the time needed to (re)build relationships of trust. It requires a multi-year commitment with a strong capacity-building focus and commitment to cross-cultural learning.

Implementing Co-Management

Practice respect. Take time to clarify what respect means to everyone “at the table” and treat everyone (and participants not directly at the table) respectfully. Keep cross-cultural differences in mind. Past trauma and historical injustices may still mean there is a need for healing and reconciliation. Empathy and patience are necessary. Acknowledge partners’ contributions and strengths. Refrain from coercing others and be aware of power differences and dynamics. Foster safe spaces so that information and opinions can be exchanged freely. Meet your responsibilities and commitments, both formal and informal, and acknowledge when you can’t. Acknowledge the critical interests of partners and stakeholders. Take every opportunity to invite partners, including government and industry, to participate in cultural events in the Indigenous partners’ communities whenever possible.

Manage yourself. The pressures of responding to the demands of a co-management relationship can be extremely difficult. Managing these pressures means taking care of yourself physically, emotionally, and spiritually too. Find a trusted friend or other mentors to talk with. Ultimately, if there aren’t sufficient supports in places to successfully carry out co-management responsibilities, this needs to be communicated early on in the process and with leadership.

Leadership matters. Each parties’ leaders must clearly transmit their intentions to the staff who will be responsible for implementation. Indigenous leaders should be committed to pursuing their communities’ goals. Non-Indigenous managers often work for Indigenous governments and they can face special challenges. These managers should, as much as possible, draw on the authenticity, authority and voice of the Indigenous communities they work for. This means continually looping back to Indigenous leadership and communities to confirm that position(s), approach and messages are aligned with and representative of the Indigenous voice. Transparent, open and frequent communications between leaders and staff are essential. Take care to weigh legal rights-holders’ (i.e. Indigenous peoples) interests against stakeholders’ interests in inclusive, respectful, and clear ways. Ensure that citizens’ values are driving the co-management process rather than the other way around.

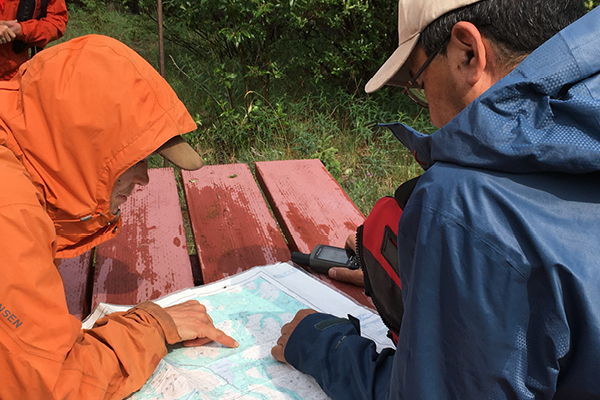

Engage continuously to build relationships and shared understanding. Work hard at understanding the social context of issues as deeply and comprehensively as possible, not just their technical aspects. Patience is important since understanding is never absolute and often accumulates slowly. Strive to establish credibility, legitimacy and trust with partners. Facilitate an open/transparent process. Ensure that all partners and stakeholders equally understand what is happening, and that nobody feels left out. Listen to community concerns and comments. Demonstrate commitment to work together. Get out on the land together. Empower and build democratic decision-making capacity in local co-management institutions; this provides opportunity for communities to create a future they can see themselves in.

Establish a high-performing decision-making process. Meet regularly, keep minutes, and make them publicly available. This keeps everyone accountable. Set clear and consistently-applied ground rules to ensure that decision-making processes are fair, equitable, and open. A neutral facilitator or an independent chair can help create neutral discussions that are recognized as such by all participants. Be clear on how parties will share information with one another, how long each party needs and can take to review the information provided by others, and what the commitments are to meeting any defined objectives. Organize meetings and events on the land, to complement indoor conversations in a meaningful way.

Respect and apply different knowledge systems. Participants will be looked to for mature, unbiased attitudes and acknowledgement of the legitimacy of values, interests, and opinions different from their own. Integration of local and traditional knowledge with scientific and technical knowledge means using both knowledge systems to complement each other, but not trying to assimilate either into the other: “Two eyes, one (shared) vision” and “two-eyed seeing” are good ways to think about this approach, but experience has shown they are not easy to achieve. Partners must persevere with their mutual efforts at learning and experimenting with how to respectfully and appropriately apply different knowledge systems, and should never give up trying.

Engage the right people for the task(s). Involved parties should approach co-management efforts as opportunities to learn together and support decision-making using the best of both knowledge systems. Provide opportunities for community members to participate in technical studies and scientific research at all stages: design, data collection, and analysis. Local or traditional knowledge studies are best performed by a community member supported by their community and (where needed) trusted outside experts. Communities should only take on technical studies after carefully assessing their internal capacity to accomplish it and ensuring that time, people, and funds are sufficient to do a job that serves the interests and needs of the community: a dedicated and experienced research team and project manager are essential.

Be flexible. Regularly review the progress and revisit timelines where needed. It will help maintain the work progress. Readjust work schedules and priorities, if needed, which will alleviate bottle-necks and also support long-term relationship-building. Anticipate just how challenging some co-management processes might be and be ready for that, either by increasing the human or economic resources capacity, or simply allowing a more realistic timeframe based on available resources at hand to get things done.

Communicate clearly, regularly, and widely. This means both between those “at the table” and also with those who aren’t. Any information conveyed should be truthful, fair, reasonably complete, and available in plain (non-technical) language: translated where necessary. Involved parties should make their approaches, strategies, ongoing technical studies, and information transfer transparent to each other. Use the tools and venues for communication that work in your community to reach people and stimulate discussion. Raising awareness about what co-management is and what it means to communities is very important. In many parts of the north communities and their leaders worked for decades to establish it: honour their work and remember why they thought it mattered.

Anticipate differences and disputes. They are an integral part of the co-management process and can almost always be resolved with prior planning and continued good faith efforts. Involved parties should build-in contingency processes in case of serious disagreements or conflicts that cannot be resolved through normal processes. Shift the emphasis from asserting positions to understanding the underlying interests – and then work towards those. Appreciate the merits of fair compromise. Address both the procedural and substantive dimensions of conflicts. Procedural dimension can include a group’s need to be included in decision-making, to have their opinions heard and to be respected as a social entity. Substantive dimension refers to interests that relate to tangible products, such as availability of firewood, fish, protection from predatory animals or stopping a major source of pollution. Include all significantly affected people (or their legitimate representatives) and parties in devising solutions. And take time to reflect on how far you’ve come already.

Learning From Others’ Experiences

Northerners have gained a lot of experience with co-management over the years since the earliest land claims were settled, and everyone is continuing to learn as they go. Here are some critical lessons learned the hard way.

- When co-management structures are new, it is important not to exaggerate their role in resolving all of the long-standing issues and create unrealistic expectations among participants.

- Do not underestimate the value of investing time and effort in a strong engagement phase. It will provide significant benefits in terms of ownership and sustainability of results.

- Remember that social dynamics have their own rhythm and cannot be forced. Developing an effective and equitable co-management regime in most contexts involves profound political and cultural change which, most of all, needs time.

- Ensure you understand the legislation and underlying rights that authorize and legitimize the organization and operation of co-management bodies, and the implementation of their decisions.

- It is possible for an organization to forget the principles that make co-management work, while still going through the motions. Elders or other respected long-term participants should be part of the process to minimize the risk of this happening.

- Besides learning from others, there is value in evaluating the process to learn not only from others, but taking time for reflection, self-evaluation and then making necessary changes.

Further Readings

Borrini-Feyerabend, G., Farvar, M. T., Nguinguiri, J. C. & Ndangang, V. A. 2007. Co-management of Natural Resources: Organising, Negotiating and Learning-by-Doing. Kasparek Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany: GTZ and IUCN. URL: https://conservation-development.net/rsFiles/Datei/CoManagement_English_Auflage2.pdf

Armitage, D., Berkes, F. Doubleday, N. 2007. Adaptive Co-Management: Collaboration, Learning, and Multi-Level Governance. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press, The University of British Columbia

Clark, D.A., Workman, L., and Jung, T.S. 2016. Impacts of reintroduced bison on First Nations people in Yukon, Canada: finding common ground through participatory research and social learning. Conservation and Society: 14(1): 1-12. URL: http://www.conservationandsociety.org/article.asp?issn=0972-4923;year=2016;volume=14;issue=1;spage=1;epage=12;aulast=Clark

McConney, P., Pomeroy, R., & Mahon, R. 2003. Guidelines for coastal resource co-management in the Caribbean: communicating the concepts and conditions that favour success. West Indies, Barbados: Caribbean Conservation Association. URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08d0b40f0b652dd001704/R8134Rep.pdf

Pereira, C.C., Pinto, R., Mohan, C., & Atkinson, S. 2013. Guidelines for establishing co-management of natural resources in Timor-Leste. Jakarta, Indonesia: Conservation International for the Timor-Leste National Coordinating Committee. URL: http://www.coraltriangleinitiative.org/sites/default/files/resources/03_Guidelines%20for%20CoManagement.pdf

Pomeroy, R.S. and Rivera-Guieb, R. 2006. Fishery Co-management: A Practical Handbook. Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing and Ottawa, Canada: International Development Research Centre. URL: https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/bitstream/handle/10625/29766/IDL-29766.pdf

Rusnak, G. 1997. Co-management of natural resources in Canada: A review of concepts and case studies. Mingma Working Paper #2. Ottawa, Canada: International Development Research Centre. URL: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/757a/8cd7368e1541215607369831b52d29a4a813.pdf.

Two-eyed seeing. URL: http://www.integrativescience.ca/Principles/TwoEyedSeeing/

Urquhart, D. 2003. Renewable Resources Council Training Handbook. Dawson District Renewable Resource Council, Dawson, YT, Canada.

Yukon Fish & Wildlife Management Board (YFWMB). 2001. Two eyes, one vision. YFWMB, Whitehorse, YT, Canada

ISSN 2369-0224 (Print) ISSN 2369-0232 (Online)

Sujata Manandhar

Sujata Manandhar was a Mitacs Accelerate Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at Climate Change Research, YukonU Research Centre, Yukon University and the School of Environment and Sustainability (SENS), University of Saskatchewan from 2016-2019. Her research mainly focused on formative assessment of an emerging Indigenous: industry water co-management regime between Champagne and Aishihik First Nations and Yukon Energy Corporation in Yukon.

Kheghaala-λiλetko (Nadia Joe)

The Principal at Green Raven Environmental, Kheghaala-λiλetko works to advance Indigenous rights and interests in water management and governance.

Douglas Clark

Douglas Clark is an Associate Professor in the University of Saskatchewan’s School of Environment and Sustainability, and an Associate Member of the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy. He has worked with northern communities for 24 years as a government employee, academic researcher, and an independent facilitator.