Addressing the growing crisis of psychological stress injuries among Canada’s public safety personnel

As has been widely documented, Canada’s public safety personnel face escalating levels of psychological stress injuries. They experience chronic exposure to potentially psychologically traumatic events, high operational demands, and stigma surrounding mental health.

By Greg Hutch (MPP'25), Director, Research and Industry, Precision AI; Partner, Melcher Studios; Past Chair, Saskatchewan Science CentreIntroduction

Download the JSGS Policy Paper

Download the Disussion Questions

There is a pressing need for targeted, evidence-based strategies and a cultural shift within public safety institutions. The challenges are no longer rooted primarily in a lack of awareness or funding, but rather institutional obstacles. Fragmented services, inconsistent program implementation, and poor coordination between agencies continue to erode the effectiveness of well-intentioned reforms, preventing meaningful progress.

Psychological stress injuries (e.g., major depressive disorder, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder) can have a lasting impact on public safety personnel; both in their ability to do their job, as well as their overall mental health and well-being (Public Safety Canada, 2019). Posttraumatic stress injuries can erode individual health, disrupt families, weaken public service delivery, and impose long-term costs on institutions and communities.

A national study found that 44.5% of public safety personnel screened positive for symptoms consistent with one or more mental disorders. Dr. Nick Carleton, an expert in clinical psychology at the University of Regina, has produced foundational research on trauma and mental health among public safety personnel, informing evidence-based policy and programming across Canada. One of the findings from Carleton and his colleagues was that these proportions are statistically significantly higher than the general population and increase with years of service and potentially psychologically traumatic event exposures (Carleton et al., 2018a).

Despite increased investments in mental health research, policies, and support programs, several studies and reports confirm that psychological stress injury rates have not meaningfully declined.

- RCMP members face worsening mental health outcomes due to frequent exposure to trauma and inadequate support. The National Police Federation calls for urgent investment in comprehensive, evidence-based mental health services. (National Police Federation, 2024).

- Among surveyed paramedics, 33% had taken medical leave, including 12% specifically for mental health (Fischer & MacPhee, 2017).

- Despite legislative reforms like presumptive clauses to simplify claims for psychological stress injuries, more needs to be done to improve access to care (Anderson & Dragatsi, 2024).

- A recent longitudinal study evidenced protecting mental health is an ongoing process (Carleton, Teckchandani and Sauer-Zavala, 2025).

Recent evidence consistently shows that posttraumatic stress injuries remain alarmingly prevalent among Canadian public safety personnel, despite expanding mental health initiatives. Persistent stigma, a shortage of qualified professionals, bureaucratic red tape, and continued pursuits of single “checkbox” solutions all continue to obstruct efforts to better support public safety personnel. The disconnect between policy intentions and actual outcomes reveals deep-rooted systemic, cultural, and logistical challenges that dilute the impact of current programs. These patterns highlight the urgent need for targeted, evidence-based strategies and a cultural shift within public safety institutions.

The Human Impact: The Humboldt Broncos Bus Tragedy and the Psychological Impact on Public Safety Personnel

The April 6, 2018, Humboldt Broncos bus crash has had a lasting impact on its victims, the victims’ families, the communities, and the public safety personnel who faced the aftermath. For many, the experience was deeply personal. These were not anonymous victims—they were neighbours, friends, and in some cases, family. Off-duty paramedic Deanndra King recalled working on “autopilot” in the chaos, her training guiding her through the unimaginable. After the incident, she experienced distress that could not be compartmentalized (Canadian Press, 2018). Experts cautioned that posttraumatic stress symptoms and operational stress injuries often surface weeks, months, or even years later (Craig, 2018; Bosker, 2019).

Nipawin Fire Chief Brian Starkell described experiencing flashbacks and a “visceral drop” in his stomach when driving past the site. “These memories, I don’t think they will go away anytime soon… that tragedy has not gone away at all” (Stober, 2019).

The Humboldt tragedy illustrates that the psychological wounds are enduring. Addressing them requires more than short-term crisis intervention It requires sustained, evidence-based mental health supports embedded into the emergency response systems.

Context: Understanding Psychological Stress Injuries in Public Safety Roles

Public safety personnel face repeated exposure to potentially psychologically traumatic events, significantly increasing their risk for a range of mental health challenges, including:

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other trauma-related disorders;

- Depressive- and anxiety-related disorders;

- Substance use disorders; and,

- Occupational burnout.

These cumulative exposures, combined with operational and organizational stressors, create a persistent and growing burden of posttraumatic stress injuries within the public safety sector (Carleton et al., 2022).

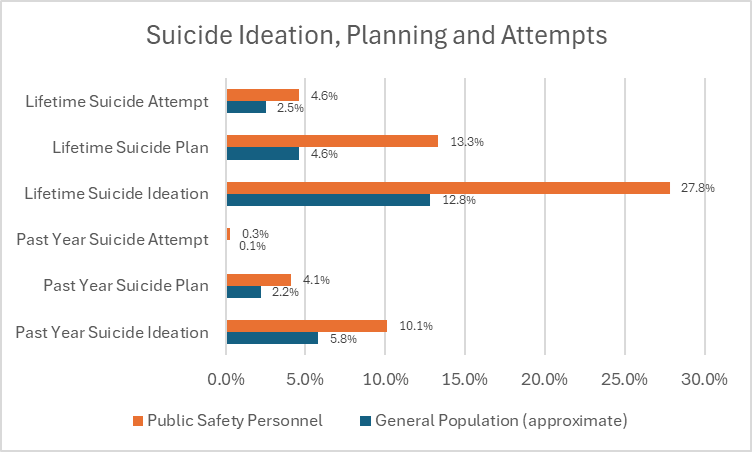

A national survey conducted by Carleton and colleagues (2018b), involving 5,148 Canadian PSP, revealed disturbingly high rates of suicidal ideation and behaviors compared to the general population. These findings, compiled from sources including Carleton, Afifi, and Turner (2017) and the Government of Canada (2016), align with or exceed international estimates for public safety personnel mental health outcomes.

SOURCE: CARLETON, AFFIFI AND TURNER, 2017; GOVERNMENT OF CANADA, 2016; HUTCH, 2025; COMPILED BY THE AUTHOR

Suicide represents the most devastating consequence of this crisis and a profound loss that reverberates through institutions, families, and communities that public safety personnel are entrusted to protect.

The mental health toll is especially severe among those facing prolonged exposure to potentially psychologically traumatic events and chronic workplace stress. Organization leaders have acknowledged the urgency of the situation. The Paramedic Chiefs of Canada (2022) have declared the current trajectory unsustainable, calling for systemic reforms that extend beyond individual institutions to build a more resilient support framework. Similarly, the Ontario Association of Chiefs of Police (2021) has warned that maintaining the status quo is both financially and operationally untenable.

The National Police Federation (2024) has further highlighted a surge in mental health disorders among RCMP members, including PTSD, generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder underscoring the widespread and escalating nature of this crisis.

The Cost of the Crisis

Claim data, from the Ontario Workplace Safety and Insurance Board, demonstrates the unsustainable economic impact of psychological stress injuries. Between January 2016 and November 2020, Ontario police officers filed 1,529 PTSD claims, costing $134 million (Ontario Association of Chiefs of Police, 2021; CBC, 2021a). In contrast, other approved claims during the same period totaled $37 million. The average PTSD claim cost was $87,873, far exceeding the cost of clinical assessments or evidence-based training (Wilson, 2016). These figures underscore the economic rationale for investing in proactive harm prevention (Carleton et al., 2022a; 2022b).

Beyond economics, there’s a public good and sustainability imperative. Fewer healthy paramedics and police mean diminished capacity to protect communities at a time when demand for their services is rising. Recruitment and retention challenges are widespread. The Manitoba Association of Health Care Professionals reports burnout, excessive overtime, and long patient wait times due to critical paramedic shortages (CBC, 2021b). The Government of Canada anticipates continued paramedic staffing shortages through 2031 (Government of Canada, 2023). The Ontario Provincial Police had over 1,000 vacant frontline constable positions—26% of its funded roles (Auditor General of Ontario, 2021). The RCMP, already strained by staffing gaps in 2007, now faces a recruitment crisis that hampers its ability to fulfill policing contracts (Government of Canada, 2007; Tunney, 2023).

The system is under immense pressure. Institutions, paramedics, and police are struggling to maintain public safety services amid external stressors (Regehr, 2017). The data paints a clear picture: the crisis is deepening, and without decisive action, it will get worse.

The consequences of Policy downloading and systemic under-resourcing

Policy downloading refers to the practice where higher levels of government—such as federal or provincial authorities—shift responsibilities, programs, or mandates to lower levels (municipalities, local agencies) without providing the necessary resources to support implementation. This often leaves local bodies scrambling to fulfill obligations without adequate funding, staffing, or infrastructure, resulting in service gaps and operational inefficiencies.

In the realm of public safety, this dynamic is compounded by systemic under-resourcing. When preventive measures and social supports are neglected “upstream,” the consequences inevitably surface “downstream” as emergencies. Public safety personnel are then left to manage crises that could have been mitigated earlier.

For paramedics, one clear example is the bottleneck in hospital emergency departments. When hospitals are unable to admit patients promptly, paramedics must remain with them—sometimes for extended periods—until admission is possible. This not only places undue stress on paramedics but also delays their ability to respond to new emergency calls.

Police services face a similar burden. Officers are increasingly called to respond to overdoses and mental health crises—situations that fall outside traditional policing roles. Alarmingly, approximately 80% of police calls are unrelated to core law enforcement functions, highlighting a systemic failure to address social and health issues through appropriate channels.

In cities like Regina and Saskatoon, the surge in overdose-related calls is now straining fire departments as well. Fire crews are frequently diverted from other emergencies, and responders face mounting mental fatigue from repeated exposure to chaotic, emotionally charged scenes. These incidents often involve distraught family members and, in some cases, the same patients multiple times in a single day. The operational toll is significant—some fire stations are left temporarily unmanned to accommodate these calls (Hayter, 2025).

By allocating resources to address social challenges before they escalate into emergencies, we can improve public service delivery and alleviate the mounting pressure on public safety personnel. Proactive funding and policy reform are not just strategic—they're essential to building a more resilient and responsive public safety system.

Current barriers to psychological stress injury mitigation

Despite growing awareness of the mental health challenges faced by public safety personnel, substantial barriers continue to impede effective, evidence-based proactive efforts, early interventions, and posttraumatic stress injury treatments. These obstacles are multifaceted, rooted in cultural, occupational, and systemic factors that shape the lived experiences of public safety personnel. The following sections explore three critical domains—cultural stigma and institutional norms, occupational and organizational stressors, and fragmented mental health supports—that collectively hinder progress toward a more resilient and responsive mental health infrastructure for public safety personnel in Canada.

Cultural stigma and institutional norms

Stigma can play a role in discouraging public safety personnel from seeking help for psychological stress injury. Multiple studies and expert sources report that fear of job loss, demotion, or reputational damage discourages help-seeking among first responders. The stigma surrounding mental health in emergency services is deeply rooted in a culture of toughness and silence. Public safety personnel often worry that seeking counseling or disclosing psychological distress could be perceived as weakness, potentially jeopardizing promotions or their standing among peers. This fear creates a substantial barrier to accessing care (Krakauer, Stelnicki & Carleton, 2020).

Occupational, operational, and organizational stressors

Occupational stressors refer to the physical, mental, and emotional pressures that occur when a worker perceives job demands as exceeding their resources or capabilities to manage them effectively. Ricciardelli et al. (2020) explored the stressors affecting public safety personnel, emphasizing that these stressors fall into distinct categories requiring different approaches to mitigation:

- Operational stressors stem from the inherent demands of the job, such as responding to emergencies, witnessing trauma, and facing life-threatening situations. These are deeply embedded in public safety work and are generally more difficult to mitigate.

- Organizational stressors, on the other hand, arise from the internal structure and culture of the workplace. These include ineffective leadership, limited support systems, bureaucratic inefficiencies, inconsistent shift scheduling, and poor communication. Unlike operational stressors, many organizational stressors are considered more manageable through targeted changes and resource investment.

Key organizational stressors identified in the research include:

- Shift work and constant vigilance, which lead to ongoing physical and mental fatigue.

- Staffing shortages, which intensify workloads and reduce recovery time.

- Chronic overtime and unpredictable schedules, contributing to burnout and diminished resilience.

- Isolation in rural and remote units, where access to specialized mental health care is limited and professional support is scarce.

Occupational stressors collectively heighten the psychological toll on personnel. Crucially, research found that many organizational challenges could be mitigated through strategic reforms—such as better staffing, streamlined administrative processes, and improved access to mental health resources.

Resource shortages: A national crisis in staffing

National workforce data show that vacancy rates and burnout levels among Canada’s public safety personnel are at their highest in more than a decade.

The CSA Group’s Canadian Paramedic Landscape Review (2024) reports that rural and remote emergency services face persistently higher vacancy rates, longer recruitment timelines, and greater reliance on part‑time or on‑call staff than urban services. These conditions contribute to service delays, increased overtime, and higher burnout risk among frontline responders.

The Canadian Institute for Health Information (2024) warns that Canada’s aging population will increase demand for emergency and health services, intensifying staffing pressures on public safety personnel.

Public Safety Canada (2025) further notes that health system pressures directly affect workloads, as paramedics and other public safety personnel are increasingly diverted into non‑traditional roles such as interfacility transfers, community paramedicine, and on‑scene triage to offset shortages in other parts of the health care system.

The Canadian Nurses Association projects a deficit of more than 60,000 registered nurses by 2030 (CNA, 2024). Hospital service gaps are already increasing calls for paramedics to perform interfacility transfers, on-scene triage, and community paramedicine — duties that blur traditional role boundaries. National mental health surveys show that over 50% of paramedics report role overload due to these expanded responsibilities, with direct links to higher rates of operational stress injuries. The nursing deficit is so large that it is reshaping the scope of paramedic work and increasing burnout risk.

Public Safety Canada’s projections warn that without immediate, coordinated investment in recruitment, retention, and mental health supports, Canada risks systemic emergency response delays and reduced resilience in the face of disasters, public health crises, and everyday emergencies.

Fragmented supports

Mental health supports for public safety personnel in Canada remain inconsistent and fragmented across provinces and agencies, partly due to the absence of a standardized national framework (Public Safety Canada, 2019). This lack of cohesion undermines early intervention and proactive efforts and limits the ability to fund and evaluate effective treatments. The result is a patchwork of services that vary in quality, accessibility, and confidentiality.

This fragmentation has tangible consequences: elevated costs, increased disability claims, higher turnover rates, secondary trauma within teams, and prolonged recovery times. Anderson and Dragatsi (2024) emphasize that while legislative advances—such as presumptive clauses for trauma-related mental disorders—have eased some burdens, public service personnel still encounter substantial barriers to timely and confidential care. They call for system-wide reforms to harmonize mental health supports, expand occupational eligibility, and reduce evidentiary hurdles to ensure equitable access across jurisdictions.

Policy recommendations

A comprehensive and coordinated policy response is essential to address the persistent barriers to psychological stress injury mitigation among public safety personnel. The following recommendations outline actionable strategies designed to strengthen mental health supports, fostering cultural change, and improving operational conditions. The recommendations emphasize the importance of strategic resourcing, stigma reduction, and robust evaluation frameworks. Together, the recommendations offer a roadmap for building a more resilient, responsive, and equitable system of care for those who serve on the front lines of public safety.

Strategic resourcing

To address the impact of policy downloading and mitigate stress-related injuries among public safety personnel, strategic resourcing must be prioritized. This includes allocating sufficient funding and support to initiatives that reduce the burden placed on frontline responders. For instance, the Saskatchewan RCMP has embedded psychiatric nurses into public safety operations to improve outcomes and prevent unnecessary escalation (SaskToday, 2023). Similarly, Regina has established a Medical Response Unit to help manage the rising number of overdose-related calls (Hayter, 2025).

Investments should also be directed toward early intervention and proactive support programs that address posttraumatic stress injuries before they escalate. Operational adjustments are essential to reduce cumulative stress experienced by personnel. Reforming shift schedules to avoid consecutive high-stress assignments and ensure adequate recovery time is one such measure. Creating quiet recovery zones within stations—equipped with calming lighting, soundproofing, and wellness tools—can offer on-the-job mental resets. The Edmonton Police Service is among the organizations that have implemented such spaces.

Peer support programs play a vital role in fostering informal, confidential check-ins and early intervention, while also helping to reduce stigma. York Regional Police has demonstrated success with its peer support model (Millard, 2020). Embedding mental health professionals into daily operations allows personnel to access care without leaving the workplace or taking time off, making mental health support more accessible and integrated.

Stress-informed task allocation, guided by data, can help identify trauma-heavy roles and rotate personnel more frequently to prevent prolonged exposure. Additionally, funding expanded wellness leave policies—distinct from traditional sick leave—can normalize proactive mental health care and recovery.

Cultural change and stigma reduction

The integration of mental health literacy throughout all phases of public safety personnel training and leadership development is key to cultivate a culture of openness, empathy, and support. This approach aims to reduce stigma, normalize recovery from psychological stress injuries, promote help-seeking behaviors, and strengthen peer support networks (Krakauer, Stelnicki, & Carleton, 2020).

Evaluating progress and success

To drive accountability, demonstrate measurable impact, and foster continuous improvement across public safety organizations, the standardized public reporting of key performance indicators is vital. The RCMP Longitudinal Study (www.rcmpstudy.ca) serves as a groundbreaking model of how rigorous, long-term data collection can shape effective mental health strategies for frontline personnel. By tracking RCMP cadets from the start of their training through their first years of service, the study provides a comprehensive framework for assessing mental health outcomes over time (Carleton, Teckchandani and Sauer-Zavala, 2025). Through the integration of metrics into this longitudinal research, the RCMP is establishing a benchmark for evidence-based mental health tools, training, and policies that hold promise for adaptation across public safety personnel sectors; indeed, there are several organizations preparing to pilot test expansions of the RCMP Study tools and training starting in the Fall of 2025 (see https://ptsslab.ca/solutions/ for details).

Conclusion

Society has a moral and operational imperative to protect Canada’s public safety personnel from avoidable psychological harm. A shift in strategy is urgently needed. With collective leadership, we can build a resilient, trusted, and sustainable support system for those who protect and serve.

Greg Hutch

Greg Hutch (MPP'25) is a leader in digital innovation with senior roles including partner at Melcher Studios, a creative technology firm specializing in VR/AR and interactive media. He is past chair of the Saskatchewan Science Centre, and former Director of IT Transformation at Viterra. With a career that spans technology and innovation, he is Director, Research & Industry at Precision AI, an agtech innovator using AI and drones for sustainable farming.

References

Anderson, G. S., & Dragatsi, H. (2024, January 19). Canadian workers at risk: Removing barriers to treatment for public safety professionals (PSP). Open Access Government. https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/article/canadian-workers-at-risk-removing-barriers-to-treatment-for-public-safety-professionals-psp/172622/

Auditor General of Ontario. (2021). Value-for-Money Audit: Ontario Provincial Police. https://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arreports/en21/AR_OPP_en21.pdf December 2021

Bosker, B. (2019, May 8). Broncos tragedy leads to focus on first responders’ mental health. 650 CKOM. https://www.ckom.com/2019/05/08/broncos-tragedy-a-turning-point-for-first-responders-mental-health/

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. (2021a). “Ontario officers have guaranteed PTSD benefits. Now the police brass wants to change that”. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/london/ontario-police-ptsd-benefits-oacp-1.6119084 August 2, 2021

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. (2021b). “Alarming paramedic shortages in rural Manitoba causing burnout, long waits, union says”. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/rural-manitoba-paramedic-staff-shortages-1.6154643 August 26, 2021

Canadian Nurses Association. (2024, February 29). Latest health workforce data confirms CNA’s predictions of critical nursing shortages. CNA News Room. https://www.cna-aiic.ca/en/blogs/cn-content/2024/02/29/latest-health-workforce-data-confirms-cnas

Canadian Press. (2018, July 14). Some first responders from Humboldt Broncos bus crash get mental-health break. Castanet Kamloops. https://www.castanetkamloops.net/news/Kamloops/289372/Some-first-responders-from-Humboldt-Broncos-bus-crash-get-mental-health-break

Carleton, R. N., Afifi, T. O., Turner, S., Taillieu, T., Duranceau, S., LeBouthillier, D. M., Sareen, J., Ricciardelli, R., MacPhee, R. S., Groll, D., Hozempa, K., Brunet, A., Weekes, J. R., Griffiths, C. T., Abrams, K. J., Jones, N. A., Beshai, S., Cramm, H. A., Dobson, K. S., Hatcher, S., Asmundson, G. J. G. (2018a). Mental Disorder Symptoms among Public Safety Personnel in Canada. Canadian journal of psychiatry. Revue canadienne de psychiatrie, 63(1), 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743717723825

Carleton, R. N., Afifi, T. O., Turner, S., Taillieu, T., LeBouthillier, D. M., Duranceau, S., Sareen, J., Ricciardelli, R., MacPhee, R. S., Groll, D., Hozempa, K., Brunet, A., Weekes, J. R., Griffiths, C. T., Abrams, K. J., Jones, N. A., Beshai, S., Cramm, H. A., Dobson, K. S., … Asmundson, G. J. G. (2018b). Suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts among public safety personnel in Canada. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie canadienne, 59(3), 220–231. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000136

Carleton, R. N., Krätzig, G. P., Sauer-Zavala, S., Neary, J. P., Lix, L. M., Fletcher, A. J., Afifi, T. O., Brunet, A., Martin, R., Hamelin, K. S., Teckchandani, T. A., Jamshidi, L., Maguire, K. Q., Gerhard, D., McCarron, M., Hoeber, O., Jones, N. A., Stewart, S. H., Keane, T. M., Sareen, J., Dobson, K., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2022a). The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) Study: Protocol for a Prospective Investigation of Mental Health Risk and Resiliency Factors. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy and Practice, 42(8), 319-333. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.42.8.02

Carleton, R. N., McCarron, M., Krätzig, G. P., Sauer-Zavala, S., Neary, J. P., Lix, L. M., Fletcher, A. J., Martin, R., Sareen, J., Camp, R. D. II., Shields, R. E., Jamshidi, L., Nisbet, J., Maguire, K. Q., Jones, N. A., MacPhee, R., Afifi, T. O., Brunet, A., Beshai, S., Anderson, G. S., Cramm, H. A., MacDermid, J., Ricciardelli, R., Rabbani, R., Teckchandani, T. A., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2022b). Assessing the impact of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) Protocol and Emotional Resilience Skills Training (ERST) Among Diverse Public Safety Personnel. BMC Psychology, 10(1), 295. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00

Carleton, R.N., Teckchandani, T.A., Sauer-Zavala, S. et al. Mental Health of Royal Canadian Mounted Police Cadets Completing Training. J Police Crim Psych 40, 180–196 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-024-09715-5

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2024, February 29). The state of the health workforce in Canada, 2022: Keeping pace with changing population needs. https://www.cihi.ca/en/the-state-of-the-health-workforce-in-canada-2022/keeping-pace-with-changing-population-needs

Craig, M. (2018, April 9). Mental health support ‘crucial’ for Humboldt crash first responders. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/4133824/mental-health-support-crucial-for-humboldt-crash-first-responders/

CSA Group. (2024). Canadian paramedic landscape review and standards roadmap. Canadian Standards Association. https://www.csagroup.org/wp-content/uploads/CSA-Group-Research-Canadian-Paramedic-Landscape-Review-And-Standards-Roadmap.pdf

Employment and Social Development Canada. (2025, March 4). Backgrounder: Foreign Credentials Recognition Program. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/news/2025/03/backgrounder-foreign-credentials-recognition-program.htmlFischer, S. L. & MacPhee, R. S. (2017). Canadian paramedic health and wellness project: Workforce profile and health and wellness trends. Prepared for Defence Research Development Canada (DRDC) / Centre for Security Science (CSS).

Government of Canada. 2007. Rebuilding the Trust. https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/cntrng-crm/tsk-frc-rcmp-grc/_fl/archive-tsk-frc-rpt-eng.pdf December 2007

Government of Canada. (2023) Paramedic in Canada. https://www.jobbank.gc.ca/marketreport/outlook-occupation/4402/ca November 29, 2023

Hayter, R. (2025, August 12). Evan Bray Show: Rise in overdoses concerning to Regina firefighter. 980 CJME. https://www.cjme.com/2025/08/12/evan-bray-show-rise-in-overdoses-concerning-to-regina-firefighter/

Hutch, G. F. (2025). Beyond the call: Addressing the growing crisis of psychological stress injuries in Canada’s paramedics and police [Master’s thesis, University of Regina].

Krakauer, R. L., Stelnicki, A. M., & Carleton, R. N. (2020). Examining mental health knowledge, stigma, and service use intentions among public safety personnel. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 949. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00949

Meyer, K. (2023, October 15). As a paramedic, I was put on the front line of strangers' tragedy — and I felt it all. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/as-a-paramedic-i-was-put-on-the-front-line-of-strangers-tragedy-and-i-felt-it-all-1.6994785

Millard, B. (2020). Utilization and impact of peer-support programs on police officers mental health. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01686

National Police Federation. (2024). Behind the badge: Mental health of RCMP members. https://npf-fpn.com/app/uploads/securepdfs/2024/02/NPF-Mental-Health-Reoport_EN_DIGITAL.pdf

Ontario Association of Chiefs of Police. (2021). Resolution 2021-09: Mandatory legislative amendments to the Workplace Safety and Insurance Act and/or WSIB policy documents relating to Bill 163, Supporting Ontario’s First Responders Act (Post-traumatic Stress Disorder), 2016.

Paramedic Chiefs of Canada. (2022). Statement on hospital offload delays in Canadian hospital emergency departments. July 13, 2022.

Public Safety Canada. (2019). Supporting Canada’s Public Safety Personnel: An Action Plan on Post-Traumatic Stress Injuries. https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/2019-ctn-pln-ptsi/index-en.aspx

Public Safety Canada. (2025). Public Safety Canada’s 2025 to 2026 departmental plan. Government of Canada. https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/dprtmntl-pln-2025-26/index-en.aspx

Regehr C, LeBlanc VR. (2017). PTSD, Acute Stress, Performance and Decision-Making in Emergency Service Workers. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017 Jun;45(2):184-192. PMID: 28619858.

Ricciardelli, R., Czarnuch, S., Carleton, R. N., Gacek, J., & Shewmake, J. (2020). Canadian public safety personnel and occupational stressors: How PSP interpret stressors on duty. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134736

SaskToday. (2023, January 17). RCMP communications centre to keep specialized nurses. https://www.sasktoday.ca/crime-cops-court/rcmp-communications-centre-to-keep-specialized-nurses-6288727

Stober, E. (2019, April 6). ‘It was a slap in the face’: First responders recall horror of Humboldt crash on anniversary. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/5138241/humboldt-crash-first-responders-stories/

Tunney, Catherine. (2023). “A recruitment ‘crisis’ threatens the RCMP’s future – the new boss has plans to turn it around”. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/rcmp-duheme-recruitment-1.6937969 August 19, 2023

Wilson, S., Guliani, H., & Boichev, G. (2016). On the economics of post-traumatic stress disorder among first responders in Canada. Journal of Community Safety & Well-Being, 1, 26-31.

Please email your feedback or suggestions on the Policy Brief to the editor: dale.eisler@uregina.ca