Repairing Health Care in Canada: Time to Take the First Step

The commitment of Canadians to a publicly funded, universally accessible health care system is beyond question. But the failure of the system to meet the needs and expectations of the public has become abundantly apparent.

By Peter Nicholson, Chair of the Board, Canadian Climate Institute; Former Deputy Chief of Staff for Policy, Office of the Prime Minister of Canada; Former Inaugural President, Council of Canadian AcademiesDownload the Discussion Questions

Despite a broadly-shared recognition that Canada’s health care system, post-pandemic, is in crisis, the federal and provincial governments remain unable to mount a collaborative approach to repair and reform. Most recently, in November 2022, negotiations between Ottawa and the Provinces broke down over provincial refusal to accept, as a condition for increased federal funding, the latest modest federal proposals for reform, in this case, related to health human resources and a national data system. Federal Health Minister, Jean-Yves Duclos, lamented that: “Premiers are forcing my colleagues to speak only of one thing: money….If there was anyone still doubting it, the current crisis is undeniable proof that the old way doesn’t work. We need to do things differently.”

The purpose of this Policy Brief is to propose how to start doing things differently.

The commitment of Canadians to a publicly funded, universally accessible health care system is beyond question. But the failure of the system to meet the needs and expectations of the public has become abundantly apparent. What has been exposed is an unwelcome truth: Canada does not have a world-class health care system. For health care to be a defining element of Canada’s national pride and identity, as many believe it to be, we owe it to ourselves to do a lot better.

Those who still believe we have among the world’s best health care system are unfamiliar with international evidence that places the overall performance of health care in Canada near the bottom among our peer group of economically-advanced countries, above only the United States. This has been demonstrated in the periodic assessments by the Commonwealth Fund—most recently ranking Canada 10th out of 11 peers—and by countless academic papers, books, and commission reports over the years.1

Unfortunately, the structure of the health care system has proven remarkably resistant to significant reform. In particular, federal cash transfers, now in the form of the Canada Health Transfer (CHT), have not been able to “buy” reform despite repeated attempts to do so. In fact, for reasons that will be explained below, federal money has reduced the incentive for reform. The CHT should therefore be ended and replaced by (a) a transfer of tax “room” from the federal to provincial governments, and (b) an increase to the federal Equalization Program so that poorer Provinces are not placed at a disadvantage. Before getting into the details, the basic rationale for the proposal is as follows.

Replacing the Canada Health Transfer

One taxpayer: While Canada has two primary levels of government, federal and provincial, there is only one taxpayer. One’s tax dollar is ultimately divided between what goes to Ottawa and what goes to one’s home Province. The basic logic of tax policy implies that the division should match as nearly as possible the jurisdictional responsibilities of each. If government X (say, a provincial government) is wholly responsible for service Y (say, the delivery of publicly-insured health care) then government X should also be responsible for raising the taxes to deliver Y. Why? Because that is the only way to establish political accountability for taxes raised and outcomes achieved. The split of one’s tax dollar between the federal and provincial governments should never create an opportunity for political blame-shifting.

Provinces control health care: In Canada, the Provinces have constitutionally-enshrined jurisdiction over provision of health care within their territory, a prerogative they guard jealously. The federal government can only plead. Consequently, it is the Provinces that should be made to weigh the public desire for better health care against public resistance to (provincial) tax increases. That calculation has been significantly distorted by the federal cash transfer which, although it is effectively unconditional, retains the politically salient association with “health”.2 Despite now covering almost a quarter of Provincial health spending, the CHT is always deemed by the Provinces to be insufficient, a claim used by provincial governments to shift some of the blame for the inadequacies of the health care system onto the federal government. By muddying the assignment of responsibility, the CHT has reduced the pressure on the Provinces to undertake the politically difficult task of health care reform. That is why the CHT needs to be replaced with something that creates a much stronger incentive for health care reform by the provincial governments that control essentially all the levers by which reform can be achieved.

Matching fiscal and jurisdictional responsibilities: The CHT should be replaced by a new fiscal regime, initially yielding the same total revenue to the Provinces, and consisting of two components: (1) a transfer of “tax points” (or what is sometimes called “tax room”) from the federal to provincial governments and for which there is long-established precedent,3 and (2) a more richly-funded Equalization program. The latter addresses the fact that the government of a poorer province has to tax its residents more heavily than a richer one in order to raise the same amount of revenue per capita, and thus to deliver approximately the same quality of a service such as health care. One hypothetical illustration of how the new regime would work is summarized in the Box below.

|

Replacing the CHT: Hypothetical Illustration New tax room could be made available to the Provinces via the GST and/or the personal and corporate income tax. Purely for purposes of illustration (not a recommendation), suppose that the current $45B CHT were replaced as follows: (i) add $3B to Equalization, leaving $42B to be permanently made available to the Provinces by (ii) a reduction of the federal GST from 5% to 4% while the Provinces (except Alberta?) increased their sales tax by one percentage point, yielding about $4.8B based on federal budgetary estimates for FY2022-23, and (iii) lower federal personal and corporate tax rates by amounts sufficient to reduce the current federal portion of these revenue sources by 17% and 5% respectively. If the Provinces fully took up this “room” their personal and corporate tax revenues would increase by about $34B and $3.4B respectively based on 2022-23 budgetary estimates. In sum, Provincial revenue collectively would increase by approximately $42B which, with the addition of $3B of Equalization transfers, would replace the CHT cash. Obviously, there are many other ways to make up the total and would be the subject of negotiation. Since the transfer of tax room would be permanent, the Provinces would have the certainty of new revenue, under their control and accountability, with which to finance health care and other services within their jurisdictions. |

From the perspective of the taxpayer, at least initially, the proposed transfer of tax points would mean that your federal tax payment would go down and your provincial tax would go up by an equal off-setting amount. Your total tax bill would be unchanged. But as time goes on, provincial governments might use the new tax room to either increase or decrease tax rates depending on a political assessment of the best trade-off between services like health care and the taxes needed to pay for them. Federal Equalization funds would meanwhile serve to offset the tax-raising disadvantage of poorer provinces. There would be several advantages:

- The new arrangement would end the CHT mythology that the funds, once in the hands of the Provinces, are reserved exclusively for health care. They are not, but the mythology has been sustained by the fact that the name of the transfer program has mattered hugely. In the arena of public perception and political accountability, the “H” in CHT has established significant federal responsibility for the performance of a system over which it has neither constitutional nor de facto authority.4

- The permanent transfer of tax room from the federal to provincial governments would give the Provinces control, and therefore certainty, over the revenue needed to support their constitutional jurisdiction for health care. This would respond to their perennial complaint that the federal CHT is both too little and, in the mid to longer term, uncertain since it is subject to Ottawa’s discretion. For purely political reasons Provinces have nevertheless welcomed an annual block of cash without responsibility for the tax rates needed to fund it. Many could therefore be expected to object to the proposed replacement of the CHT, preferring instead to have revenue without accountability and someone else to share blame for any shortcomings of the health care system.5

- The new model would establish approximate horizontal fiscal equity across the Provinces—i.e., the governments of poorer provinces would receive more, via increased Equalization, than they now do from the equal-per-capita CHT.

- Without the word “health” explicitly attached to the (Equalization + tax room) transfer, it would finally be clear to the public that health care policy and delivery is essentially the sole responsibility of provincial governments. And without Ottawa to share the blame for underperformance, provincial governments would have a stronger incentive to organize the delivery of health care so as to achieve greater quality and public satisfaction per dollar spent.

Response to Concerns

Those who would nevertheless argue to retain the CHT claim that without the threat of withholding federal funds from a Province that violates the Canada Health Act, our national health care system would be at risk of fragmenting, thus ending one of this country’s greatest acts of nation building. Certainly, with more reform pressure being directly felt by the Provinces, there would be experimentation and innovation. Indeed, that would be welcome and would give rise to better practices to be adopted and adapted by other Provinces. At present, and perversely, attempts by Ottawa to encourage national collaboration with the promise of increased financial transfers have instead degenerated into demands for more unconditional transfers. Without that bone of contention, Provinces might actually be more prepared to voluntarily adopt national approaches in areas of shared interest—e.g., reciprocal recognition of medical credentials; collective negotiation of drug prices; interprovincial portability of insured services.

Almost four decades after passage of the Canada Health Act, the principle of universally affordable access to health care is now firmly embedded in this country, both institutionally and politically. There is essentially zero risk of back-sliding into a US-style system that is scorned around the world and increasingly within the US itself. The fact is that there are many other models of health care delivery, founded on majority public-sector involvement, that deliver better results and greater citizen satisfaction than Canada’s sclerotic system does—see Annex. The alternative is not the US model. But because that model is familiar to Canadians, it has been used as a bogeyman by those who wish to defend the status quo.

One particular concern in this regard is that without the discipline imposed by the federal CHT, some Provinces might ignore the Canada Health Act’s implicit prohibition of private insurance for “medically-necessary” services.6 Parallel privately-insured care, it is argued, would create a two-tier system in which (a) privately-insured patients could get better and/or quicker care, (b) the public system would be left with the more complex, less profitable cases, and (c) physicians and nurses would desert the public system in search of financial reward, thus depriving the public system of talent and/or increasing its costs in order to remain competitive.

This set of concerns is understandable if the US system were the only comparator. But the fact is that virtually every other health care system among the economically-advanced countries permits some version of private insurance for medically-necessary services, with many physicians working in both systems simultaneously. But in no case—at least among the nine countries (other than the US and Canada) evaluated by the Commonwealth Fund—has the public system been significantly compromised. It turns out that private insurance is used by a relatively small percentage of patients to receive quicker care in non-urgent situations, thus relieving some pressure on the public system. This has not led to a slippery-slope exodus of medical talent and resources from the public to the private system because the scope of the latter remains small so long as “free” care remains universally available.7

Unfortunately, there is a perception in Canada that “private”, in a health care context, equals “American”. This misconception has made it virtually impossible to even consider how the issue of providing some amount of medically-necessary care outside the public system might be managed, as it is in other advanced countries, while ensuring that publicly-insured care remains universally available and is not degraded. The high level of performance and public satisfaction with health care in, for example, Australia, Germany, and Norway suggests that public and (limited) private insurance of medically-necessary care can in fact coexist positively.

Finally, since almost all aspects of health care delivery fall within exclusive provincial jurisdiction, provincial governments are within their right to design systems of their own choosing subject to bearing the political consequences. In the federal systems of Germany and Australia, the national government has paramount constitutional authority over health care and is therefore in a position to forge national approaches. In Canada, the constitutional division of powers in respect of health care is just the opposite. That leaves Ottawa with only its spending power to encourage a national approach. This may be effective when initiating a national program in a field of provincial jurisdiction, but not for sustaining one whose principle has become established. In the case of health care, it is extremely unlikely that the voters of any province would agree to a design that undermined affordable and universal access to medically-necessary care. Even so, it is a choice that should always be open in a democracy.

Conclusion

The federal government’s website describing Canada’s health care system notes that: “In 1977, under the Federal-Provincial Fiscal Arrangements and Established Programs Financing Act, cost-sharing was replaced with a block fund, in this case, a combination of cash payments and tax points. This new funding arrangement meant that the provincial and territorial governments had the flexibility to invest health care funding according to their needs and priorities.”

Forty-five years later, with medicare now far more well-established, it is time to finish the job initiated in 1977 and convert the remaining cash portion of the federal grant (the CHT) into further tax points, thus giving provincial governments “the flexibility to invest health care funding according to their needs and priorities.” Federal “training wheels” in the form of the Canada Health Transfer are no longer needed. What is needed is significant reform of health care delivery to move Canada into the top rank of peer group countries. Much of what should be done is well-known, the result of decades of experience and analysis. Now, the political incentive to act must be strengthened. The first step is to replace the Canada Health Transfer.

Peter Nicholson

Peter Nicholson has served in numerous posts in government, business, and higher education. His public service career included positions as Clifford Clark Visiting Economist in Finance Canada; Deputy Chief of Staff, Policy in the Office of the Prime Minister; and Special Advisor to the Secretary-general of the OECD. Dr. Nicholson’s business career included senior executive positions with Scotiabank and BCE Inc. He retired in 2010 as founding president of the Council of Canadian Academies, an organization that conducts expert panel studies of scientific issues related to public policy. He is currently the Chair of the Board of the Canadian Climate Institute. Dr. Nicholson is a Member of the Order of Canada and the Order of Nova Scotia and is the recipient of five honorary degrees.

Endnotes

1 The periodic Commonwealth Fund rankings are considered to be the gold standard for assessment of health system performance among affluent countries—see Annex.

2 The Canada Health Act of 1984 (CHA) is actually a fiscal statute that simply ties eligibility to receive the CHT to a Province’s maintenance of publicly-insured health care that is universal and accessible, covers medically-necessary services, and is interprovincially portable. But the use of the transferred funds is completely unrestricted in the hands of the Provinces. Although there have been occasional disputes between the Provinces and Ottawa regarding the interpretation of certain criteria in the CHA, there has never been a significant withholding of CHT funds.

3 The history of federal funding transfers for health, and the debates to which this has given rise over the decades, have been well summarized by Naylor et al.

4 The existing role played by Health Canada, and other federal activities that impinge on health (e.g., support of research; Public Health Agency of Canada; food inspection; national border issues, and others), would be unchanged. From a jurisdictional perspective, the proposed replacement of the CHT is entirely a fiscal matter, normally the purview of Finance Canada.

5 A decision to end the CHT and to lower federal tax rates rests entirely with the federal government. Similarly, a decision to increase provincial tax rates to move into the new “room” created by the federal government would rest with each provincial government. Everyone’s interest would be served if all parties came to a negotiated agreement on the precise mechanism of CHT replacement but provincial objection could not block federal action.

6 There are several private sector providers of health insurance in Canada to cover services that are not defined as medically-necessary, the precise definition of which is determined by individual Provinces and differs to a small extent across the country. Most Provinces explicitly prohibit private insurance of medically-necessary services that are publicly insured. Any physician is allowed to opt-out of the publicly insured system but the financial incentive to do so is severely limited by provincial legislation, the details of which vary among Provinces but within narrow limits.

7 Canada already has an informal two-tier system in which care can be accessed, for a price, in the US or often more affordably in several other countries.

Annex: International Perspective on Health Care in Canada

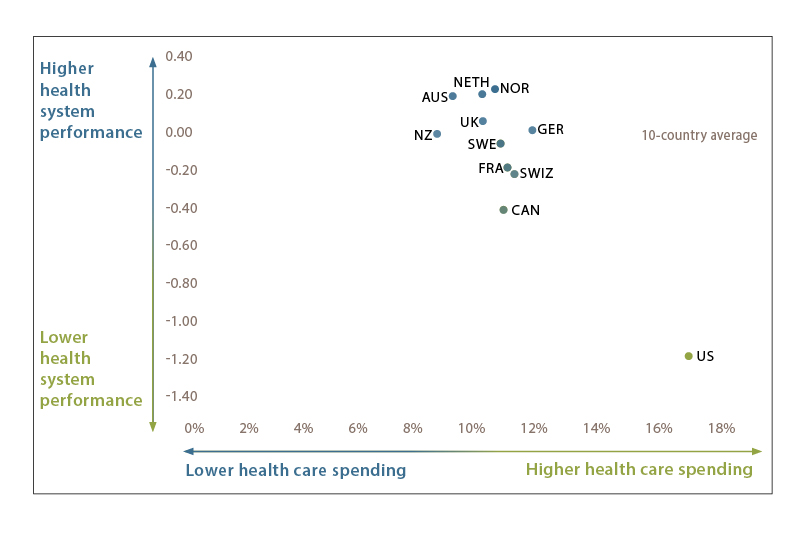

The Commonwealth Fund regularly assesses national health care performance based on an extensive set of indicators (71 measures in the 2021 analysis). The ranking, which is undertaken every few years, is considered to be the gold standard for assessment of health system performance among affluent countries. While there is some unavoidable arbitrariness in the choice of metrics, and particularly in the methodology for combining them into a single indicator, the method is sufficiently robust to separate the best performers from the mediocre. Canada clearly falls into the latter category. This is illustrated in Chart 1, with health care spending as a percent of GDP on the horizontal axis. Norway leads the latest ranking closely followed by the Netherlands and Australia. The health care performance of the United States, the highest spender by far, is nevertheless in distant last place. Canada ends up 10th of the 11 countries at the bottom of the non-US peer group.

Chart 1: Health Care System Performance Compared to Spending

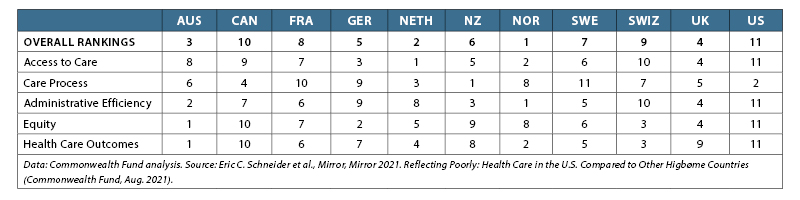

Table 1 summarizes the 11 country rankings across the five evaluation categories used by the Commonwealth Fund. The full report contains a wealth of detail underlying the rankings in each category.

- Access to care includes measures of health care’s affordability and timeliness.

- Care process includes measures of preventive care, safe care, coordinated care, and engagement and patient preferences.

- Administrative efficiency refers to how well health systems reduce documentation and other bureaucratic tasks that patients and clinicians frequently face during care.

- Equity focuses on income-related disparities, based on standardized data across the 11 countries, in the access to care, care process, and administrative efficiency performance domains.

- Health care outcomes refer to those health outcomes that are most likely to be responsive to health care.

Canada ranks reasonably well only in respect of “Care Process” (measures of preventive care, safe care, coordinated care, and engagement and patient preferences), and is a dismal 10th out of 11 in Equity and Health Care Outcomes.

Table 1: Health Care System Performance Rankings

It is revealing to consider the health care governance structure of three of the top-rated systems: Australia, Germany, and Norway. Like Canada, both Australia and Germany have federal systems of government. But unlike Canada, ultimate authority for most aspects of health care policy, regulation, and funding rests at the federal level. Formal institutional arrangements that foster collaboration with State governments—or in Norway with municipalities—are features of all three systems. But federal dominance creates a very different health care governance environment than in Canada where Provincial dominance is constitutionally-enshrined.

In countries where the central government is dominant in respect of health care it is evidently much easier to forge a more uniform national model. The central government is in a position to combine its funding support to states/municipalities with reform and regulatory initiatives. In Canada, where the onus is reversed, the federal government has only been able to use cash transfers to encourage (“bribe”) provincial reform. This has not been very effective since, for a variety of political reasons, Ottawa’s bargaining power in the health arena has been weak.

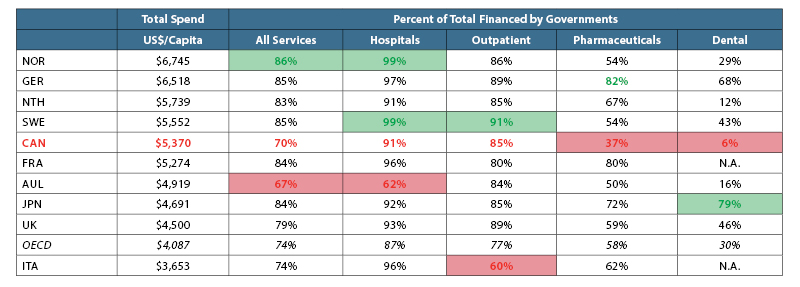

Government coverage of health services: It may come as a surprise to many Canadians that among highly developed countries, except for the US, the fraction of health care that is publicly funded in Canada is relatively low at 70%. Western European countries are typically in the range of 85%—see “All Services” column in Table 2, drawn from OECD data, where the rows are ordered by decreasing per capita spending on public and private health care combined. (The highest percentages in each column are coloured green, and the lowest are in red.) Among the 10 peer countries illustrated, Canada ranks last in public coverage of both pharmaceutical expense (37%) and dental expense (6%). This is to be compared for example with Germany where the public coverage of these costs is 82% and 68% respectively. On the other hand, governments in Germany spend almost 50% more per capita than governments in Canada to cover all health care expenses. But remarkably, governments in Australia spend 12% less per capita than in Canada yet provide greater coverage of drugs and dental care while, according to the Commonwealth Fund assessment, delivering more effective health care overall.

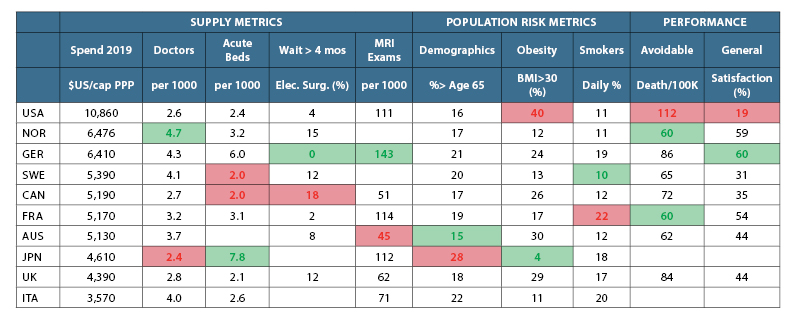

Health systems at a glance: Table 3 is based on data from the Commonwealth Fund. For each metric, the green cell is the best in the sample, and the red cell the worst. (Blank cells are those for which data was not available.)

Canada generally ranks at the lower end of four “supply “metrics—especially for hospital beds and wait time for elective surgery. Our risk factors, other than obesity, compare well. Canada also performs reasonably well on a key performance measure—the number of deaths per 100,000 population considered to have been preventable or otherwise amenable to health care (72 in Canada vs 60 for the best performers—Germany and Norway). Survey results give Canada at best a middling ranking for general public satisfaction with the health care system (35%) well below Norway and Germany (about 60%), but far above the US at 19%. The same survey found that 9% of Canadians believe that the system needs to be completely rebuilt while, not surprisingly, almost a quarter of Americans have that opinion.

Table 2: Public Financing of Health Care (OECD 2019)

Table 3: International Comparisons: Sample of Commonwealth Fund Data (2017)

There are noteworthy cross-country variations among the “supply” and “risk” factors in the table—e.g., Japan and Germany have far more hospital beds per capita than other peer countries. Japan, US, UK and Canada have relatively few doctors per capita. Very few Germans, French and Americans wait more than 4 months for elective surgery, whereas almost 20% of Canadians do. Japan’s population is old and has a relatively high percentage of smokers, but per capita health spending is among the lowest, perhaps helped by a very low incidence of obesity. But the UK and Australia have comparatively high obesity rates, yet relatively low health spending.

The message of these figures is that there is no simple relationship among the factors thought to influence health status, health outcomes, and the cost of providing care. Virtually the only robust rule is that the health of a population correlates positively with economic development together with an equitable sharing of its benefits.