Saskatchewan’s Forgone Potash Windfall: Collecting a Fair Public Return

The price of potash doubled in 2022, adding $10 billion to the value of Saskatchewan's pink gold. But the provincial government collected only a quarter of this windfall. This policy paper highlights the need to improve royalties and taxes to ensure a fair return for the people of Saskatchewan.

By Erin Weir, Former MP and Consulting Economist, Silo StrategyIntroduction

Download the JSGS Policy Paper

Download the Discussion Questions

Saskatchewan has one-third of the world’s potash. This fertilizer’s price doubled in 2022, creating windfall profits of $10 billion.

Although the Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan (PCS) was privatized in 1989,1 the potash itself – like any other mineral – still belongs to the province. For more than a decade, economists including yours truly,2 Jack Mintz,3 Jack Warnock,4 John Burton,5 and Jim Marshall6 pointed out that flawed royalties and taxes under successive governments have failed to capture the value of this resource.

Last year’s windfall highlights the need to collect a fair return for the people of Saskatchewan, who own the resource, from the mining companies that extract it. Although potash prices moderated this year, the value sold in 2023 already exceeds 2021 and every previous year.7

The Ukraine war dramatically increased demand and prices for Saskatchewan potash. Facing economic sanctions, Russia and Belarus slashed their combined potash production from one-third of global output in 2021 to an estimated one-fifth in 2022.8

While Saskatchewan mined the same volume of potash in both years,9 the value of those sales leapt from $7.6 billion in 2021 - already above any prior year - to $18.0 billion in 2022.10 An extra $10.4 billion arose not from additional production, investment or risk-taking by mining companies but from international events beyond their control.

This sum is enormous for Saskatchewan, enough to pay off the provincial General Revenue Fund’s entire operating debt.11 Ten billion amounts to $8,500 for every Saskatchewan resident,12 seventeen times the value of the $500 Affordability Tax Credit cheques the provincial government sent only to adult tax-filers.

The potash windfall could have been distributed to Saskatchewan people through cash transfers or tax cuts, used to pay off debt, saved for future generations, or invested in provincial infrastructure and services such as healthcare, education and housing. To fund these worthy goals, the Government of Saskatchewan would have needed to collect much of the ten billion on behalf of resource owners.

The provincial Public Accounts, reported by fiscal year, indicate that potash revenues nearly doubled from $1.3 billion in 2021-22 to $2.4 billion in 2022-23 - an additional $1.1 billion from Crown royalties and the potash production tax. Although resource surcharge revenues are not broken down by commodity, the flat 3% surcharge on ten billion of incremental potash sales would have added $0.3 billion.

Therefore, Saskatchewan’s royalty and tax system collected $1.4 billion of the potash windfall. It left the lion’s share in mining company coffers, which contributed to temporarily higher share prices, continuing dividend increases and higher corporate tax payments.

Table 1: Saskatchewan Potash and Corporate Tax Revenues, 2021 – 2022 ($ billions)13

|

Year |

Potash Sales |

Provincial Revenues |

||||

|

Surcharge |

Royalties & Production Tax |

Corporate Tax |

Total |

|||

|

2021 |

$ 7.6 |

$ 0.2 |

2021-22 |

$ 1.3 |

$ 1.0 |

$ 2.5 |

|

2022 |

$18.0 |

$ 0.5 |

2022-23 |

$ 2.4 |

$ 2.0 |

$ 4.9 |

|

Increase |

$10.4 |

$ 0.3 |

Increase |

$ 1.1 |

$ 1.0 |

$ 2.4 |

Provincial corporate tax revenues rose from $1.0 billion in 2021-22 to $2.0 billion in 2022-23. These amounts include all industries, but even if the additional billion came entirely from potash companies, the province still received less than a quarter of last year’s potash windfall: $2.4 billion out of $10.4 billion.

The industry itself confirms these figures. Saskatchewan Mining Association fact sheets indicate that, from 2021 to 2022, the value of potash sales jumped by more than $10 billion even as the tonnage mined edged up by less than 1%. It reports that payments from potash companies to local, provincial and federal governments rose by $3.4 billion,14 with federal corporate taxes adding a billion to the total from provincial Public Accounts.15

The Mining Association also reports that potash payrolls grew from 5,400 employees earning a combined $0.8 billion in 2021 to 5,800 employees earning $0.9 billion in 2022. Potash companies directly employ only 1% of Saskatchewan’s workforce but pay well.16

The industry’s purchases of goods and services from Saskatchewan businesses were unchanged at $1.8 billion in 2021 and 2022.17 The total of $2.7 billion paid to Saskatchewan workers and suppliers last year amounted to just 15% of potash sales from the province. While potash payrolls and procurement are especially significant to communities with mines, they pale in comparison to potential revenues of up to $10 billion.

Normally, the owners of a commodity would receive most of the benefit from a relative increase in its price. Of last year’s $10-billion potash windfall, the Saskatchewan government collected only one-quarter on behalf of resource owners, the federal government collected one-tenth, and the mining companies kept two-thirds after tax.

Potash Prices

Profits from rising prices could offset losses when prices fall. In theory, temporary windfalls might be needed to cover mine costs and provide a normal profit rate over time.

But unlike commodities priced in volatile spot markets, potash prices are mostly negotiated through contracts. Almost all of Saskatchewan’s offshore potash sales are through Canpotex, an export cartel permitted by the federal Competition Act. This market power helps to quickly ratchet up potash prices and manage subsequent declines.

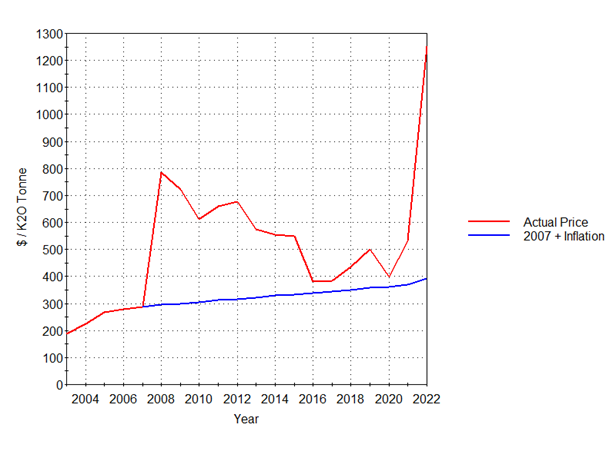

Figure 1: Saskatchewan Potash Prices, 2003 - 202218

In Canadian dollars per tonne of potassium oxide (K2O), the average price received by Saskatchewan mines rose from $200 in the late 1990s and early 2000s to almost $300 in 2007. If that record price had continued rising with inflation, it would be $400 today.

In fact, potash jumped to almost $800 per K2O tonne in 2008 and then tapered off for a decade, but never much below $400. The surge to $1,250 in 2022 created a huge new windfall on top of prices that had stayed ahead of inflation for 15 years.

Saskatchewan’s 2023-24 Mid-Year Report forecasts $663 per K2O tonne.19 Although a sharp drop from 2022, this price still exceeds every prior year except 2008, 2009 or 2012 and is more than double the 2007 price. Given prevailing exchange rates since 2015, halving the above prices approximates American dollars per tonne of potassium chloride (KCl), a metric often reported by the industry.

Mosaic and Nutrien, created by PCS merging with Agrium, produce 90% of Saskatchewan’s potash from nine mines built in the 1960s.20 Since they trumpeted record profits in the mid-2000s, potash prices have increased more than inflation. Similarly, prices are now higher than when K+S built the Bethune mine between 2012 and 2017 or when BHP’s board of directors decided to proceed with the new Jansen mine in 2021.21

Potash Profits

Given recent increases in food prices, journalists and politicians have scrutinized grocery store profits. Canada’s largest grocery company, Loblaw, collected after-tax earnings of just under $2 billion in 2021 and again in 2022.22

Meanwhile, fertilizer companies more than doubled their after-tax earnings, reported in American dollars: from US$1.6 billion to US$3.6 billion at Mosaic and from US$3.2 billion to US$7.7 billion at Nutrien.23 Adjusting for the exchange rate, Mosaic more than doubled Loblaw’s profit and Nutrien raked in five times as much. Yet there has been little political or media interest in profits from this part of the food supply chain.

Companies account for provincial resource charges differently. Nutrien includes Crown royalties in the “cost of goods sold,” but treats the potash production tax and resource surcharge as subsequent deductions from gross margin. Mosaic includes all these charges in the cost of goods sold, reducing its reported gross margin. Fortunately, both companies report provincial resource charges separately, making it possible to recalculate their costs and margins on a comparable basis excluding royalties and taxes.

Nutrien’s financial reports go back to 2017. In prior years, PCS and Agrium had separate financial reports. PCS had stopped production at its New Brunswick mine in 2016, before Nutrien permanently closed it in 2018 noting its “ability to increase potash production in Saskatchewan at a significantly lower operating and capital cost.”24

Reports from Nutrien’s Potash segment exclusively reflect Saskatchewan mines. From 2017 to 2022, the annual cost of mining and transporting potash from Rocanville, Allan, Vanscoy, Lanigan, Cory and Patience Lake edged up from US$1.1 billion to US$1.2 billion. Meanwhile, the soaring price of potash boosted profits at these mines from US$1 billion to US$6.7 billion.

Table 2: Nutrien’s Potash Sales, Costs, Profits, Royalties & Taxes, 2017 - 2022 (US$ millions)25

|

Year |

Sales |

Costs |

Mine Profits |

Royalties & Taxes |

Share of Profits |

|

2017 |

$2,048 |

$1,064 |

$984 |

$210 |

21% |

|

2018 |

$2,664 |

$1,115 |

$1,549 |

$311 |

20% |

|

2019 |

$2,603 |

$1,038 |

$1,565 |

$352 |

22% |

|

2020 |

$2,146 |

$1,129 |

$1,017 |

$255 |

25% |

|

2021 |

$4,036 |

$1,178 |

$2,858 |

$573 |

20% |

|

2022 |

$7,899 |

$1,210 |

$6,689 |

$1,339 |

20% |

Provincial royalties and resource taxes consistently amounted to little more than 20% of mine profits. As profits skyrocketed, the proportion paid to the Saskatchewan public did not increase.

Unlike Nutrien, Mosaic produces some potash outside the province, accounting for Brazilian potash in its Fertilizantes segment. From 2017 through 2022, Mosaic’s Potash segment comprised 0.6 million tonnes of finished product each year from Carlsbad, New Mexico plus between 7.3 and 8.6 million tonnes annually from Belle Plaine, Colonsay and Esterhazy.26

In this period, Saskatchewan consistently produced 93% of Mosaic’s North American potash.27 The following table assumes Saskatchewan likewise accounted for 93% of the Potash segment’s sales and costs. Even if the true percentages vary slightly, the trends displayed overwhelmingly reflect Saskatchewan mines.

The annual cost of mining and transporting potash from Belle Plaine, Colonsay and Esterhazy remained stable at US$1.2 billion. Profits at these mines jumped from US$0.5 billion in 2017 to US$3.6 billion in 2022. Provincial royalties and taxes consistently amounted to below 30% of these profits.

Nutrien and Mosaic report that costs edged up much less than inflation. Meanwhile, soaring potash prices multiplied profits. Provincial royalties and resource taxes rose along with mine profits but are not collecting a large or increasing share.

Potash profits not captured by royalties and resource taxes may be subject to corporate income tax after deducting losses from other business segments, head office costs and financing expenses. But corporate taxes are not payments for the resource since they apply to all industries and do not mostly accrue to the province. Specifically, taxable corporate profits are subject to a 15% federal rate and a 12% Saskatchewan rate.28

Table 3: Mosaic’s SK Potash Sales, Costs, Profits, Royalties & Taxes, 2017 - 2022 (US$ millions)29

|

Year |

Sales |

Costs |

Mine Profits |

Royalties & Taxes |

Share of Profits |

|

2017 |

$1,723 |

$1,227 |

$496 |

$142 |

29% |

|

2018 |

$2,022 |

$1,281 |

$741 |

$199 |

27% |

|

2019 |

$1,966 |

$1,195 |

$771 |

$212 |

27% |

|

2020 |

$1,878 |

$1,279 |

$599 |

$176 |

29% |

|

2021 |

$2,443 |

$1,179 |

$1,264 |

$302 |

24% |

|

2022 |

$4,844 |

$1,232 |

$3,612 |

$1,041 |

29% |

Royalty and Tax Exemptions

Examining potash royalties and taxes explains how Saskatchewan people receive such a modest share of soaring mine profits. The basic royalty is 3% of potash production from Crown land and the resource surcharge is 3% of all potash sales.30

In September 2022, the provincial government quietly instituted a three-year royalty holiday of up to $100 million for new mines producing at least 2 million K2O tonnes.31 The rationale for this incentive is unclear given that BHP’s board of directors had already decided in 2021 to proceed with the new Jansen mine even with significantly lower potash prices.32

The potash production tax, introduced in 1990, comprises a base payment that is creditable against a profit tax. The base payment is fixed between $11.00 and $12.33 per K2O tonne. Output from new capacity added since 2005 enjoys a ten-year holiday from base payments.33

Royalties and the Saskatchewan Resource Credit had been deductible from the base payment. These deductions increased with the price of potash to an extent that the fixed base payment generated “very little revenue.” The 2019 provincial budget ended the deductions over the objections of potash companies.34

As the above tables show, restoring the base payment slightly increased potash production tax payments in 2019 even as the value of potash sales decreased slightly. However, the base payment remains capped at $12.33 per K2O tonne, less than 1% of last year’s average price.

Crown royalties, the resource surcharge and the base payment provide a minimum return on potash extracted from the province. They amounted to about 7% of sales at 2022 prices. The only mechanism designed to collect a significant share of mine profits is the profit tax: 15% of the first $77 per K2O tonne plus 35% beyond that.35

From 2017 through 2022, Nutrien consistently reported costs of about US$100 per KCl tonne.36 Dividing by 0.61 to convert to K2O and multiplying by 1.30 to convert to Canadian dollars indicates costs of just over C$200 per K2O tonne. The first $77 of mine profit after that is taxed at only 15%. Therefore, the amount by which potash prices exceed the 2007 level of $300 should be taxed at 35%.

Even allowing for higher costs per tonne at Mosaic and K+S, the profit tax alone should have collected $3.5 billion of last year’s $10-billion windfall. In fact, it collected closer to half that amount because it applied to closer to half of potash production.

In 2003, the Government of Saskatchewan exempted future output above the average sold in 2001 and 2002.37 Annual potash sales have almost doubled from 8 million K2O tonnes then to more than 14 million now.38

For companies that began producing potash in Saskatchewan after 2002, annual output above 1 million K2O tonnes is exempt. K+S has already surpassed this threshold and BHP promises initial production of nearly 3 million K2O tonnes in 2026.39

The 2008 potash boom underscored this perpetual exemption’s cost.40 Rather than closing the loophole, the Government of Saskatchewan announced in 2009 that potash companies must include at least 35% of their previous year’s sales in calculating profit tax.41

Over a third of potash production is already exempt from the profit tax. Expanding existing mines and opening the Jansen mine could push this exemption up to two-thirds.

Applying the 15% or 35% tax to only 35% of potash profits would collect no more than 12% of total profits. Even with the 3% Crown royalty and 3% resource surcharge, that hardly constitutes an adequate return to the people of Saskatchewan as potash owners.

Royalty and Tax Recommendations

Analysts from across the political spectrum have made the case for stronger potash royalties and taxes. Former provincial Minister of Finance Eric Cline had ushered in the 2003 profit tax exemptions as Minister of Industry and Resources. University of Regina Press will soon publish his book, Squandered: Canada’s Potash Legacy, which concludes that it is past time to revamp royalties and taxes to collect a better return for the people of Saskatchewan.

The 2015 provincial budget pledged “a review of the entire potash royalty and taxation regime” but potash companies opposed a review and it was never conducted.42 The Government of Saskatchewan has fiercely defended provincial jurisdiction over natural resources without using that authority to collect an adequate provincial return.43

Low royalties and taxes in Saskatchewan left about a billion dollars of last year’s potash windfall to Ottawa. Because provincial resource charges are deducted in calculating taxable profit, raising them would reallocate some federal revenue to Saskatchewan. Each additional dollar collected through provincial royalties or resource taxes would reduce federal corporate taxes by 15 cents, provincial corporate taxes by 12 cents and after-tax corporate profits by 73 cents.44

One could question the necessity of the ten-year base-payment holiday for additional capacity, the resource surcharge cut from 3.6% to 3%, and the $100-million royalty holiday for new mines.45 These measures rolled out just as potash price jumps provided far stronger incentives.

But taken together, the base payment, resource surcharge and Crown royalty still ensure a minimum return on potash extracted from the province. At least on Crown land, these levies could be combined into a single “revenue-based royalty at seven per cent” as envisaged by University of Calgary business economists Duanjie Chen and Jack Mintz.46 It could be bumped up by a percentage point as Saskatchewan’s Official Opposition proposed last year.47

The far more serious problem is that the current profit tax fails to collect a substantial share of mine profits. Its scope, write-offs and rates should be considered.

Exemptions limit the profit tax to the 8 million K2O tonnes sold in 2001 and 2002 plus up to 1 million K2O tonnes per new entrant. This scope is under two-thirds of Saskatchewan’s current potash output. Present regulations would allow the profit tax base to shrink to just 35% of sales. Restoring the profit tax to cover all tonnes is the simplest and most important improvement the Government of Saskatchewan could make to its potash royalty and tax system.

Since 2003, it has allowed companies to write off 120% of new potash investment in calculating the profit tax. As a result, they paid almost no profit tax in the early 2010s.48 K+S reports suggest it has paid very little profit tax.49 BHP is unlikely to pay profit tax for several years as it writes off the Jansen investment.

Allowing companies to write off the full cost of investments is not controversial, but the extra 20% distorts investment decisions at public expense.50The deduction should be limited to 100%. As JSGS Executive-in-Residence Jim Marshall concluded in 2019:51

Since the industry has had [two decades] of benefit from the exemption provided on new production, and as many years to benefit from these generous capital allowances, these two features of the potash tax system might be the first areas one should examine in looking for ways to restore Saskatchewan tax rates to more historic levels.

Because the potash profit tax applies only after investments are paid off, it does not tax the normal return to capital. Instead, it is essentially a tax on “economic rent,” which reflects the value of the resource over and above the labour and capital used to extract it.

In principle, the provincial government should aim to collect all the economic rent. In practice, a 100% tax would remove the incentive for companies to maximize profits.

Chen and Mintz calculated that, if the revenue-based royalty were creditable against the rent tax, a 70% rate could maintain the same investment incentive as the current fiscal regime.52 Such a system would have collected $7 billion of last year’s $10-billion windfall.

Chen and Mintz later proposed that a 45% tax on potash rent would keep Saskatchewan’s “marginal effective tax and royalty rate” below the average of other potash-producing jurisdictions.53 But New Brunswick, which then boasted the lowest marginal rate, no longer produces potash.54

It is not obvious why Saskatchewan should worry about somewhat lower royalties and taxes in places like New Mexico, Israel and Jordan that produce far less potash.55 It seems unlikely that western companies like Nutrien, Mosaic, K+S or BHP would invest in the other major potash producers: Russia and Belarus. As the world leader in potash reserves and output, Saskatchewan can charge more for this resource.

A comprehensive review of potash royalties and taxes could help determine the optimal profit tax rate. Even if Saskatchewan policymakers are worried about competition from other potash jurisdictions, there is clearly room to charge more than 35%. It is unclear why multibillion-dollar potash companies need a reduced 15% rate on their first $77 of profit per tonne.

The available information and analyses point toward the following reforms:

- Simplify the Crown royalty, resource surcharge and base payment to guarantee a minimum return from potash extracted;

- Broaden the profit tax to cover all tonnes of potash produced;

- Limit write-offs to 100% of the amount a company invests; and

- Increase the potash profit tax rate to collect a fair share of ongoing resource rents and future windfalls for the people of Saskatchewan.

Erin Weir

Erin Weir is a consulting economist with Silo Strategy and the former Member of Parliament for Regina–Lewvan. In completing three university degrees, he won medals for the highest graduating averages in Economics at the University of Regina and in Public Administration at Queen’s University. The Saskatchewan Institute of Public Policy (a forerunner to Johnson Shoyama) published his first paper on provincial resource taxation, Saskatchewan’s Oil and Gas Royalties: A Critical Appraisal, in 2003. Erin’s career began in the federal public service with the Treasury Board Secretariat, the Department of Finance and the Privy Council Office. He went on to work for the Canadian Labour Congress, the Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists, and the United Steelworkers – the largest union of Saskatchewan potash miners. He gained global experience as Senior Economist with the International Trade Union Confederation, the umbrella organization of national labour centrals in more than 160 countries.

Endnotes

[1] John Burton, Potash: An Inside Account of Saskatchewan's Pink Gold (Regina: University of Regina Press, 2014) and Erin Weir, “Privatizing Potash was a Costly Mistake,” The Leader-Post (August 27, 2010), page B10.

[2] Erin Weir, “Maximize Public Gain from Potash,” StarPhoenix (September 3, 2010), page A10; “Time to Review Potash Royalties,” StarPhoenix (February 10, 2011), page A8; and “Room to Alter Potash Royalties,” StarPhoenix (November 1, 2011), page A8.

[3] Jack Mintz, “The Potash Royalty Mess,” National Post (October 14, 2010).

[4] John W. Warnock, Exploiting Saskatchewan’s Potash: Who Benefits? (Regina: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, January 2011).

[5] Burton, Potash: An Inside Account.

[6] Jim Marshall, “Saskatchewan Potash Taxes and Royalties: Is it Time for a Review?,” Policy Brief (Regina: Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy, January 2019).

[7] Saskatchewan Energy and Resources, “Saskatchewan’s Mineral Sales by Commodity” at https://dashboard.saskatchewan.ca/business-economy indicates potash sales of $7.7 billion from January through August 2023. As referenced below, potash sales throughout 2021 amounted to $7.6 billion.

[8] U.S. Geological Survey, “Potash,” Mineral Commodity Summaries (January 2023), page 2.

[9] The Saskatchewan Mining Association reports 23 million tonnes of KCl mined each year (Saskatchewan Potash 2021, page 2 and Saskatchewan Potash 2022, page 2). The Saskatchewan Bureau of Statistics reports 14 million tonnes of K2O sold each year (Economic Review 2022, page 2).

[10] Saskatchewan Bureau of Statistics, Economic Review 2022, page 4 and Excel Tables.

[11] This debt was $9.9 billion as of March 31, 2022. Government of Saskatchewan, Public Accounts 2022-23, Volume 1, Summary Financial Statements, page 78.

[12] The province’s population was almost exactly 1.2 million on July 1, 2022. Saskatchewan Bureau of Statistics, Economic Review 2022, page 2.

[13] Government of Saskatchewan, Public Accounts 2022-23, Volume 1, page 84. (Provincial revenues are only reported by fiscal year. On a fiscal-year basis, potash sales increased from $9.4 billion in 2021-22 to $16.7 billion in 2022-23. Saskatchewan Finance, Budget 2023-24, page 43.)

[14] Payments to all levels of government rose from $2.0 billion in 2021 to $5.4 billion in 2022. Saskatchewan Mining Association, Saskatchewan Potash 2021 and Saskatchewan Potash 2022.

[15] Given the 12% provincial corporate tax and 15% federal corporate tax, it seems likely that somewhat less than a billion went to Regina and more went to Ottawa. KPMG, “Substantively Enacted Income Tax Rates for Income Earned by a General Corporation for 2023 and Beyond,” Canadian Corporate Tax Tables (June 30, 2023).

[16] Provincewide employment was 581,500 in 2022. Saskatchewan Bureau of Statistics, Economic Review 2022, page 2.

[17] Saskatchewan Mining Association, Saskatchewan Potash 2021 and Saskatchewan Potash 2022.

[18] For each year, the price is calculated as “Value of Mineral Sales” divided by “Volume of Mineral Sales” for potash from Saskatchewan Bureau of Statistics, Economic Review 2022, Excel tables. Inflation is Saskatchewan’s “Consumer Price Index” from the same source.

[19] Saskatchewan Finance, 2023-24 Mid-Year Report (November 27, 2023), pages 5 and 8.

[20] The only new operating mine is K+S, which produced 2 million KCl tonnes at Bethune in 2022 (K+S, 2022 Annual Report, page 36) out of 23 million KCl tonnes produced in the province (Saskatchewan Mining Association, Saskatchewan Potash 2022, page 2).

[21] Saskatchewan Trade and Export Development, “Largest Investment in Saskatchewan’s History as BHP Moves Forward on Jansen Potash Mine Project,” News Release (August 17, 2021).

[22] Erin Weir, “A Windfall Tax to Fight Food Inflation Should Target Commodity Producers,” Globe and Mail (April 17, 2023), page B4.

[23] Mosaic, 2022 Annual Report, page 4 and Nutrien, 2022 Annual Report, page 4.

[24] Nutrien, “Nutrien Announces Permanent Closure and Impairment of New Brunswick Potash Facility,” News Release (November 5, 2018).

[25] Sales are “Net sales” from Nutrien, 2022 Annual Report, page 44; 2020 Annual Report, page 30; 2018 Annual Report, page 42. Costs are “Cost of goods sold” minus “Royalties in COPM” from 2022 Annual Report, page 76 for 2021 and 2022 or 2.5% of sales for prior years. Mine profits are “Gross margin” plus Crown royalties. Royalties and taxes are “provincial mining taxes” plus Crown royalties.

[26] Mosaic, SEC Form 10-K 2022, page 10; SEC Form 10-K 2021, page 10; SEC Form 10-K 2020, page 12; SEC Form 10-K 2019, page 13.

[27] Minimum: 7.3/(0.6 + 7.3) = 0.924; Maximum: 8.6/(0.6 + 8.6) = 0.935

[28] KPMG, Canadian Corporate Tax Tables.

[29] Sales are 93% of “Net sales” from Mosaic, 2022 Annual Report, page 10 and 2019 Annual Report, page 10. Costs are 93% of the remainder of “Cost of goods sold” minus “Canadian resource taxes” and “Royalty expense”. Mine profits are “Gross margin” plus “Canadian resource taxes” and “Royalty expense”. Royalties and taxes are “Canadian resource taxes” plus “Royalty expense”.

[30] The Subsurface Mineral Royalty Regulations, 2017 simplified the Crown royalty to 3% from the previous royalties ranging from 2.1% to 4.5% described in detail by Duanjie Chen and Jack Mintz, “Fixing Saskatchewan’s Potash Royalty Mess: A New Approach for Economic Efficiency and Simplicity,” SPP Research Papers, Volume 6, Issue 7 (February 2013), page 2. The resource surcharge was increased from 3% to 3.6% in 1993 and reduced back to 3% between 2006 and 2008. Saskatchewan Finance, Corporation Capital Tax Resource Surcharge, Information Bulletin (March 2012), page 5.

[31] Saskatchewan Cabinet Secretariat, Order in Council 424, 425, etc. (September 15, 2022) and Saskatchewan Energy and Resources, Potash Information Circular (February 2023), page 4.

[32] Saskatchewan Trade and Export Development, “BHP Moves Forward on Jansen Potash Mine Project.”

[33] Saskatchewan Energy and Resources, Potash Information Circular (February 2023), page 2.

[34] Saskatchewan Finance, Budget 2019-20, page 54, and David Giles and David Baxter, “Producers Not Happy with Changes to Saskatchewan’s Potash Production Tax,” Global News (March 22, 2019).

[35] Saskatchewan Energy and Resources, Potash Information Circular (February 2023), page 3.

[36] Nutrien, 2022 Annual Report, page 44; 2020 Annual Report, page 30; 2018 Annual Report, page 42.

[37] Saskatchewan Industry and Resources, “New Measures Benefit Potash Industry,” News Release (August 14, 2003) and Potash Information Circular (February 2023), page 3.

[38] Saskatchewan Bureau of Statistics, Economic Review 2022, Excel tables.

[39] K+S reports 2.0 million KCl tonnes in 2022 Annual Report, page 36 and BHP promises 4.35 million KCl tonnes in Gabriel Friedman, “BHP to Start Recruiting Hundreds to Operate World’s Largest Potash Mine in Saskatchewan,” Financial Post (January 1, 2023). A KCl tonne is 0.61 K2O tonnes.

[40] Erin Weir, “Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap: Saskatchewan’s Multi-Billion Dollar Resource Giveaway,” Briarpatch (December 1, 2008).

[41] Saskatchewan Energy and Resources, “Government Ensures Fairness with Potash Production Tax Changes,” News Release (Nov. 20, 2009) and Potash Information Circular (February 2023), page 3.

[42] Saskatchewan Finance, Budget 2015-16, page 13 and Alex MacPherson, “Potash Firms Defend Royalty Rules,” StarPhoenix (February 4, 2019), page A1.

[43] Erin Weir, “Sask. Giving Away Natural Resources,” StarPhoenix (April 22, 2023), page A8 and “Potash Royalties Should be Higher,” The Leader-Post (April 29, 2023), page A8.

[44] These figures reflect the corporate tax rates in KPMG, Canadian Corporate Tax Tables, assuming taxable potash profits are reported in Canada.

[45] Saskatchewan Finance, Corporation Capital Tax Resource Surcharge, page 5 and Saskatchewan Energy and Resources, Potash Information Circular (February 2023), pages 2 and 4.

[46] Chen and Mintz, “Fixing Saskatchewan’s Potash Royalty Mess,” page 12.

[47] Jeremy Simes, “Sask. NDP Propose 1% Royalty Hike; Moe Pondering Minimum Wage Increase,” The Leader-Post (May 3, 2022), page A3.

[48] Erin Weir, “Royalty Structure Hurting Sask.,” StarPhoenix (March 21, 2011), page A6; Duanjie Chen and Jack Mintz, “Potash Taxation: How Canada’s Regime is Neither Efficient Nor Competitive from an International Perspective,” SPP Research Papers, Volume 8, Issue 1 (January 2015), page 11.

[49] K+S, Group Payment Report 2021, page 6 indicates €7 million to the Ministry of Finance (i.e. resource surcharge) and €6 million to the Minister of the Economy (i.e. Crown royalties). Group Payment Report 2022, page 5 indicates €15 million to the Ministry of Finance (i.e. resource surcharge) and €22 million to the Minister of the Economy (i.e. Crown royalties and likely some potash production tax).

[50] Chen and Mintz, “Fixing Saskatchewan’s Potash Royalty Mess,” pages 6 and 10.

[51] Marshall, “Saskatchewan Potash Taxes and Royalties,” page 4.

[52] Chen and Mintz, “Fixing Saskatchewan’s Potash Royalty Mess,” page 13.

[53] Chen and Mintz, “Potash Taxation,” pages 8 and 14.

[54] Laura Brown, “Could the Shuttered N.B. Potash Mine Reopen? Premier Says Yes, Company Says No,” CTV Atlantic (April 27, 2022).

[55] U.S. Geological Survey, “Potash,” page 2.