Anxiety and Anger on the Prairies: The Challenge to Federalism

In all the post-election hand-wringing, angst and analysis about western alienation these days, the most surprising thing is some people are genuinely surprised it has come to this. At least they seem that way in Ontario and Quebec. It kind of tells you all you need to know about how we find ourselves in this situation.

By Dale Eisler, Senior Policy Fellow, Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public PolicyIn all the post-election hand-wringing, angst and analysis about western alienation these days, the most surprising thing is some people are genuinely surprised it has come to this. At least they seem that way in Ontario and Quebec. It kind of tells you all you need to know about how we find ourselves in this situation.

There has been a phalanx of people venturing west from Ottawa on “listening missions” to hear about what is fuelling the anger. They are seized with tackling several pertinent questions. How did it come to this? What can be done about it? Are people really serious about this Wexit succession from Canada “thing”? Is it real or just a passing fad and will cooler heads prevail? How do Saskatchewan and Alberta voices get heard in the federal government and cabinet? No one actually puts it this way, but you can’t help but sense a subtext of “what’s wrong with you people, anyway?”

They’re all good questions. But the fact they’re being asked should give you a hint about the separate worlds people live in. Forget the two solitudes of Canada. There are three, and always have been.

As with any existential issue, if in a federation one group feels alienated from the rest to the point that people believe the costs outweigh the benefits of the relationship, then you’ve got trouble. It’s been that way in Canada, to varying degrees, since the beginning. The sentiment ebbs and flows. Today the mood in much of the West has the feel of a rising tide. But at the same time, the very nature of federalism is to deal with these pressures. By definition it allows the governing flexibility at the national level and more local autonomy necessary to ease regional divisions and tensions. For the most part, it has worked well for Canada, a massive, thinly populated country that is divided by region, economics, culture, history and language. It’s a tough country to govern. In spite of those structural realities, Canada is seen around the world as one of the great successes of federalism.

To a point that’s true. But then again has Canadian federalism really been tested? It’s had its moments, specifically with the two Quebec secessionist referendums that took Canada to the brink, the conscription crises of 1917 and 1944, and the FLQ October crisis of 1970, which all had French-English origins. There has also been a succession of Eastern and Western protests. But as a peaceable kingdom, Canada certainly hasn’t faced the stress tests of other federations, such as the former Yugoslavia or Spain. Or, for that matter, the greatest challenge federalism has ever faced, the U.S. civil war. Somehow federalism in the U.S. was able to withstand one of the bloodiest internal conflicts in modern history, and more than 150 years later remains a united, sort of, nation.

As the engagement with the West proceeds in an effort to defuse the emotions laid bare in the federal election results, the focus inevitably shifts to the policy solutions. There are clearly layers of significant irritants, many of them deeply embedded in the psychology of the Prairie West. The questions are: is there a policy fix, and, is it feasible?

The short answer to the first question is perhaps. The answer to the second is it’s political, and probably not.

That rather pessimistic view should not be interpreted that western alienation will turn into a full-blown secession from Canada movement. In the cold light of day, any objective analysis will unequivocally demonstrate that separation and the union of Alberta and Saskatchewan in a new nation will be poorer and weaker economically than as a part of Canada.

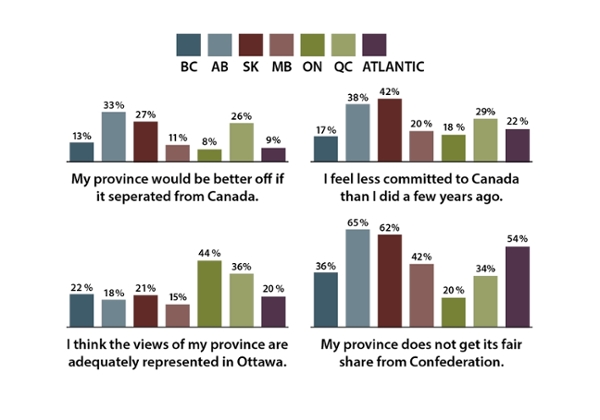

But emotions stirred by politics aren’t always rational. So the powerful feelings of alienation in the West need to be acknowledged, taken seriously and addressed as much as possible. As the graph below of public opinion in Canada done by Ipsos Research in the wake of the federal election shows, there is a deep fault line between the provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta and the rest of Canada.

Chart 1: Views on Unity – by Province/Region

It’s worth noting that support for separation in Alberta is higher than that in Quebec, and it’s even slightly higher than Quebec in Saskatchewan. The inverse, of course, is that in the immediate aftermath of the election, when emotions were running at a fever pitch in Alberta, two-thirds of the population did not support the idea of separation. But it would be foolish to assume the issue is simply going to fade away. It won’t because it is deeply woven into the fabric of the two provinces.

Identifying a policy approach requires understanding the root causes of why Alberta and Saskatchewan feel the way they do. One can trace origins of the issue back to tariffs and National Policy. But, of course, that huge western grievance dating back generations was addressed when Canada and the U.S. signed their free trade agreement in 1989.

A seldom considered starting point is the founding culture of Alberta and Saskatchewan. It’s no coincidence they both became provinces and joined confederation on the same day in 1905. At the time they were at the forefront of immigration to Canada, establishing rural agriculture economies and attracting people, largely from Europe, seeking a new life. Erica Gagnon, an immigration researcher, described it this way: “Many motivations brought immigrants to Canada: greater economic opportunity and improved quality of life, an escape from oppression and persecution, and opportunities and adventures presented to desirable immigrant groups by Canadian immigration agencies … For the thousands of immigrants who were inspired to emigrate in search of greater economic opportunities and improved quality of life, the Canadian West presented seemingly infinite possibilities. This category of immigrants encompassed populations of Hungarians, French, Icelanders, Romanians, Chinese, and Ukrainians.”1

In effect, the settlers of the Prairies came to the “New World”. It was not so much a case of choosing Canada or the U.S. They were pursuing the dream of freedom, opportunity for prosperity and success. It was the promise of upward social mobility. It didn’t matter where you came from or your ethnicity, work hard, get an education and you can have a good life. It’s also called the American Dream. The Canadian Prairies offered that same hope.

That vision of what the Prairies represented to immigrants was, at one level, fundamentally different from the founding of Canada itself. At its core, Confederation was about the recognition and accommodation of group rights, specifically the French and English. It’s explained this way by Donald Smiley, of the University of British Columbia: “Canadian federal experience has centred around two major themes. The first relates to cultural dualism, the desire and ability of French- and English- speaking Canadians to survive as such and to use the governmental institutions which they respectively dominate in order to ensure this outcome.”2 One can argue that the French-English group linguistic rights, an ethos which defines central Canada’s sense of nationhood, and the Prairie individualism where your ethnicity matters less, is an important psychological division that, in part, explains the West’s alienation. There is no changing history and we need to learn to live with it.

But, for today’s purposes, there are more practical and contemporary reasons for the Prairies feeling the way they do. Mostly they relate to issues of the economy and the absence of a political voice that’s taken seriously in federal decision-making. Some ascribe it to a lack of respect. The two most crucial are the region’s oil and gas economy, and what are perceived by some to be federal-provincial fiscal arrangements, specifically Equalization, that penalizes the Alberta and Saskatchewan resource-based economies. Address those two and the West will feel less aggrieved.

The Energy-Environment Conundrum

It can be argued that the challenge of energy and the environment—more specifically the oil and gas sector versus climate change—presents a conflict where the differences are essentially irreconcilable. In other words, you can’t have a strong and growing oil and gas economy and a national climate change strategy that meets Canada’s goals set out in the Paris Accord. Of course, Norway has proven you can have both. The Scandinavian nation has built a sovereign wealth fund of more than $1 trillion, almost exclusively from offshore oil revenues, money that is used to support transition to a clean energy economy. And Norway is continuing to expand its oil and gas output.

For Canada, the economy-environment issue goes to the heart of federalism. Provinces have constitutional jurisdiction over the development of natural resources, and the environment is a shared federal-provincial responsibility. But there is a caveat. Two courts in the carbon price challenge by Saskatchewan and Ontario have said the climate issue is an urgent national issue, which means Ottawa has jurisdiction to act unilaterally under its authority of “peace, order and good government” in section 91 of the Constitution.3

Moreover, the oil and gas economy is a cornerstone of the national economy. According to Statistics Canada, in 2018 it represented seven per cent of the Canadian economy, larger than the finance and insurance sectors combined. But unlike financial services, which are more dispersed through the national economy, oil and gas is primarily focused in Alberta. Thus, a downturn in oil and gas has an intense regional impact. In 2017, the oil and gas sector directly supported 143,000 jobs, and the energy sector itself indirectly supported almost 900,000 jobs in Canada.4 By comparison the auto industry directly employs about 125,000.5

As daunting as the oil and gas-climate change paradox might be, the Trudeau government in its first incarnation claimed you can have both—a strong energy economy and a viable climate change policy. Since then, it has been blamed, in some measure unfairly, for a weakened oil and gas sector that is primarily the result of a several external factors. One was a precipitous drop in the price of oil, coupled with an expansion in oil sands production prior to 2015 without a corresponding expansion of pipeline takeaway capacity. More to the point, since then were new regulatory measures as part of the Trudeau government’s climate change strategy.

The result has led to a crippling loss of confidence, costing billions of dollars, with energy investors leaving Canada for more welcoming opportunities elsewhere, primarily in the U.S.

The primary symbol of this malaise in the sector has been the inability to get pipelines built that would move Canadian bitumen to tidewater and provide access to the global market. Again, much of that has been beyond the government’s control, specifically legal challenges largely linked to Indigenous rights. As a demonstration of its commitment to the sector, the Trudeau government bought the Trans-Mountain Pipeline (TMX) project from Kinder Morgan, which was abandoning it in frustration over the regulatory impasse. The Trudeau government’s intent is to see the project completed, most likely in a consortium with several First Nations. If it happens, it would help at least ease some of the Prairie anger. At the same time, for political purposes in Alberta and Saskatchewan, the paralysis in getting TMX approved is being blamed on the Trudeau government. In fact the regulatory regime governing TMX was the one engineered by the previous Harper government.

Equalization and Inequity

Another long-standing major irritant for Alberta and Saskatchewan is the Equalization system. Successive governments in the two provinces, of all political stripes, have complained about the treatment of resource revenues as part of Equalization. The program is based on the principle of fiscal capacity. It applies the average of provincial tax rates across the provinces to determine how much revenue each province would generate if it had the average rate. The five tax categories in the calculation are personal income tax, business income tax, consumption taxes, property taxes, and 50 per cent of resource revenues. Provinces with revenues that fall below the national average receive equalization to bring them to the average. Ones above the average get zero. An important fact is that provinces do not “pay into” Equalization, as some of the critics like to say. Such a claim is a fallacy. It is funded entirely from federal revenue.

The crux of the issue for Alberta and Saskatchewan is twofold. First is that natural resource revenues are included in the calculation. The argument is that provinces like Manitoba and Quebec, which have large hydro power sectors, do not have those revenues included in their calculation. That too is a fallacy. They in fact are included. But as Crown-owned utilities, and to keep consumer power rates low, the provinces provide power on essentially a cost basis, whereas nonrenewable resources revenues are based on the open-market price. The second, first raised by former Saskatchewan Premier Brad Wall, is that 50 per cent of Equalization should be paid to all provinces on a per capita basis. But rather than get into a fight with the Harper government, the Wall government abandoned a lawsuit against Ottawa on the issue that had been launched by his predecessor, NDP Premier Lorne Calvert. The frustration expressed by Saskatchewan is evident in a comparison of federal transfers with Manitoba. In 2019-20 Manitoba received total federal transfers of more than $4.2 billion. Saskatchewan received $1.7 billion. Included in Manitoba’s total was more than $2.2 billion in Equalization.6

Blaming, and complaining to, the federal government about the formula has been a favourite tactic of Alberta and Saskatchewan governments for many years, and there have been multiple attempts by previous federal governments to address concerns. For example, Stephen Harper’s government was elected in part on restoring “fiscal balance” to Canada. In his government’s first budget, Harper excluded 50 per cent of resources revenues from the Equalization formula, put a cap on fiscal capacity, and introduced a 10-province standard, instead of five, to calculate fiscal capacity.7 The changes briefly reduced the pressure from some provinces, but didn’t fully resolve the underlying issue of the treatment of provincial resource revenues. It’s interesting to note that if non-renewable resource revenues were excluded from Equalization, the effect would be to reduce the amount of Equalization paid by Ottawa. Aside from lowering the federal deficit, it would not mean payments to Alberta and Saskatchewan.

What all this illustrates is that the solution to the issue rests with the provinces. The question isn’t whether a program like Equalization to ensure reasonably similar levels of service for all Canadians is good or bad. It’s how distribution is determined between provinces.

In his statement calling for a “new deal with Canada” in the wake of the federal election, one of Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe’s three demands, along with an end to the carbon tax, and construction of pipelines, was a new Equalization formula “that is fair to Saskatchewan and Alberta.”8 By coincidence, Premier Moe is currently the chair of the Council of the Federation, which is the voice of the provinces. He should show leadership, seize the opportunity and call on the Council to meet and sort out the differences that exist between the provinces on the Equalization formula, reach an agreement on how the program should work, and present it to the federal government to implement. Of course that’s not going to happen. There is no agreement amongst the provinces. Quebec, Manitoba. New Brunswick and PEI will always favour inclusion of resources revenues. Alberta, Saskatchewan and B.C. will always disagree. So, it’s better to blame the federal government for the situation.

Conclusion

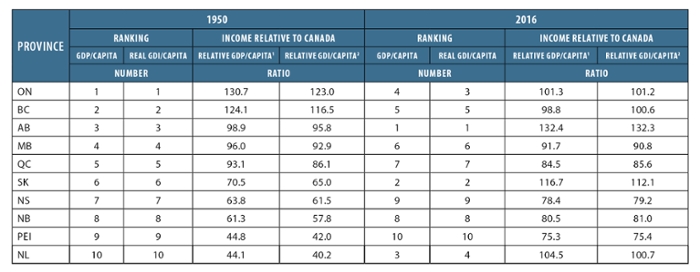

The bottom line should be obvious. There are no easy answers to solving the problem of western alienation. It is deeply rooted in the culture of the region, the nature of a geographically and economically diverse nation. It is also not new. The degree of alienation might rise and fall depending on economic and political circumstances, but it has been part of Prairie psychology for generations and likely always will be with us. However, it should also be kept in perspective. As Chart 2 shows, the reality is that Alberta and Saskatchewan rank as the top two provinces in terms of income per capita. Over time since 1950, their economic position in the federation has improved to put them ahead of other provinces.

So while there are policy prescriptions that can ease the tensions, they will require concessions and a willingness to work together and overcome our differences in the national interest. Talk of separation is not a solution. Rather, it’s a symptom of the problem, one that all governments, working together, must address.

Chart 2: Nominal and real provincial per capita income relative measures, 1950, 2016

ISSN 2369-0224 (Print) ISSN 2369-0232 (Online)

References

3 https://sasklawcourts.ca/images/documents/CA_2019SKCA040.pdf

4 p. 12 2018 Energy Fact Book, NRCan; Industry Profiles, 2018, Mining and Oil and Gas Extraction Industry, Government of Alberta

5 https://www.international.gc.ca/investors-investisseurs/assets/pdfs/download/vp-automotive.pdf

6 Department of Finance Canada, Federal Transfers to Provinces and Territories

7 https://budget.gc.ca/2007/plan/bpc4-eng.htm

8 https://www.saskatchewan.ca/government/news-and-media/2019/october/31/letter-to-prime-ministerDale Eisler

Prior to joining the JSGS, Dale Eisler spent 16 years with the Government of Canada in a series of senior positions, including as Assistant Deputy Minister Natural Resources Canada; Consul General for Canada in Denver, Colorado; Assistant Secretary to Cabinet at the Privy Council Office in Ottawa; and, Assistant Deputy Minister with the Department of Finance. In 2013, he received the Government of Canada’s Joan Atkinson Award for Public Service Excellence. Prior to joining the federal government, Dale spent 25 years as a journalist. He holds a degree in political science from the University of Saskatchewan, Regina Campus and an MA in political studies from Vermont College. He also studied as a Southam Fellow at the University of Toronto, and is the author of three books.