The Panama Papers and Public Trust: The Challenge for Governments

Timing is everything. In recent weeks, millions of Canadians were in the final stages of filing their income tax for 2015, which you might say is an annual personal tally we each do on the cost of our citizenship. Meanwhile, south of the border Americans are in the midst of a particularly nasty U.S. Presidential season, where income inequality and accusations that the political system is rigged to benefit the wealthy have stirred a wave of populist, anti-establishment anger. Then, along come the Panama Papers.

By Dale Eisler, Senior Policy FellowAnd sure enough, in what’s termed the biggest leak of financial data in history, there is evidence proving what everyone already suspected. That is, the world’s wealthiest people, some of them senior political figures, stash their money in offshore tax havens and shell companies to avoid paying taxes in their home countries. In other cases some do not attempt to hide their aversion to tax rates. They simply take up residence elsewhere to avoid Canadian taxes.

Think about that for a moment. The super rich think they’re not rich enough and want more. They hire smart tax experts who counsel them to invest their money in obscure, sometimes poor Third World nations that attract capital with the promise of no or little tax. In most cases, these investments are perfectly legal.

So, if it’s not illegal, what’s all the indignation and outrage about? Good question.

The answer is something we like to call the social contract. It’s an unwritten convention, developed over generations of democratic, representative government that basically says “we’re all in this together.”

What that means is we all do our part, work hard and pay our taxes for the benefit of the nation. Some people will do better than others and become wealthy, which is not only to be expected, but welcomed. Personal success and the accumulation of wealth is a good thing. It’s how progress happens. But what is also expected is that if you do well personally, you pay your tax share because your success is built on the economy and society developed and paid for by the current and previous generations of taxpayers. You didn’t become rich all by yourself.

In Canada, unlike the U.S., we have done a better job of avoiding excessive concentration of wealth in a few hands. Sure, we have our own elite class of the super rich, but the degree of income and wealth inequality in Canada hasn’t reached the absurd levels as in the U.S. Canada still has a strong, vibrant and growing middle class, and poverty levels have actually been declining for more than a decade. But having said that, it’s also true the gap between the super rich and everyone else in Canada continues to grow.

As yet, we don’t exactly know how many wealthy Canadians or corporations will be identified in the Panama Papers. Given the sheer amount of data, this is certain to drag on for months. Actually the number doesn’t matter. What does is the effect that evidence of tax avoidance by the wealthy has on public trust in our institutions, whether government or private sector.

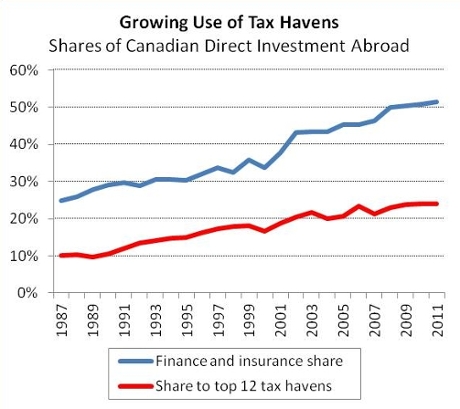

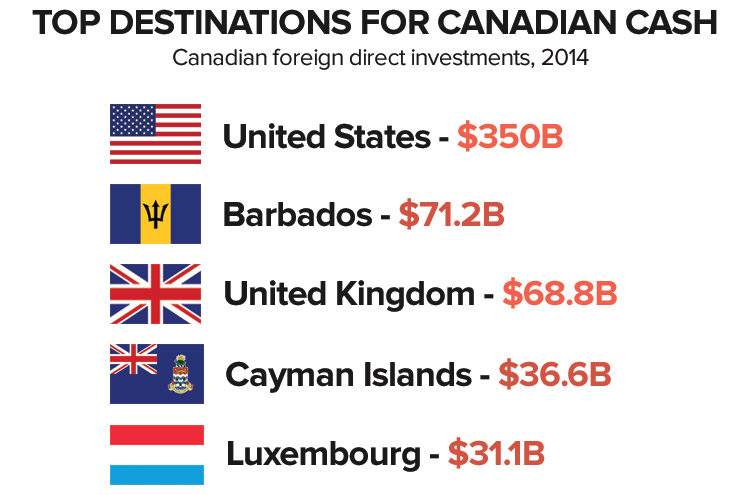

Already we’ve heard the estimates that the Canada Revenue Agency fails to collect upwards of $7 billion in taxes annually on money sent to offshore tax shelters. So it’s not as if anyone should be surprised.

But confirming what we already suspected doesn’t mean there won’t be consequences. What the Panama Papers do is further entrench in the public mind that not everybody is treated equally, and that if you’re wealthy you can afford to find ways to avoid taxes that the average person must pay.

This presents a challenge both to public policy makers and leaders of private sector financial institutions. Government needs tax policy that recognizes the importance of incentives to encourage productive investment, but also doesn’t turn a blind eye to offshore investments for the sole purpose of avoiding Canadian tax on income earned in Canada. Finding the right balance in a tax system is a constant struggle. Key to that balance is tax competition, where national governments, and those at the sub-national level, compete to attract investment by offering competitive tax rates.

Tax competition can help promote good governance by pressuring governments in a global economy to strive for an investment climate that is attractive to investors, but also balanced with the broader public interest. Governments need to use taxpayers’ dollars efficiently. The environment includes a competitive tax rate, but also other factors such as social and political stability, a sound legal system, transparency and a good quality of life. Tax havens that compete for capital purely on the basis of low or no taxes and invest little in quality of life public assets provided by other nations distort global investment for purely private interests.

Our major financial institutions need to step up as well. It’s not good enough to shrug and simply say that tax planning and putting money in offshore tax havens is not illegal. This is not necessarily a question of pure legality. It has to do with trust in our major institutions.

The most recent Edelman Trust Barometer, which tracks trust levels worldwide, finds that 45 per cent of Canadians lack trust in their major institutions.1 It measures public trust of government, business, media and NGOs and found that trust among Canadians rose slightly in the past year. The increase is considered at least partly due to the honeymoon effect of a new federal government. But the research also shows less trust of institutions among people with lower incomes.

While relative to many other nations Canadians still express higher levels of trust, the fact that close to half the population says it lacks trust in our public and private institutions should be cause for concern. You can be certain that the Panama Papers, and the ongoing focus on tax avoidance by the wealthy, will help further erode trust.

According to Gabriel Zucman, an economist at the University of California, Berkley and author of “The Hidden Wealth of Nations”, the Panama Papers only scratch the surface of worldwide tax avoidance. He draws a direct connection to growing wealth inequality.

“Tax havens are one of the prime reasons why inequality is rising and may continue to rise in the future. The inability to have a well-functioning tax system at the top end raises the risk of an ever-increasing trend of rising inequality, and that’s not something we want,” says Zucman. “If we want to deal with rising inequality and rising wealth concentration seriously, then we need to make these forms of tax dodging much, much more limited.”2

Zucman’s analysis is not without its critics, but, as one reviewer put it, the most original part of his book is that Zucman “offers the most comprehensive evaluation to date of the scope of the tax-haven problem. Zucman came up with a brilliant new way of calculating the wealth hidden in tax havens by comparing reported financial assets and liabilities in the world’s financial centers.”3 (American Prospect, The Shame of Tax Havens, February 2016)

If the federal government and financial institutions do not address this issue, they do so at their own peril. Both should see responding to the fallout from the Panama Papers as an opportunity to demonstrate they recognize the unfairness of a tax system that allows the rich to avoid paying their taxes, while the rest of the population does its part.

Collectively through the OECD and G20, many nations, including Canada, have been trying to make progress on ending global abuse of illegal and deceptive tax havens. More than two years ago, the OECD launched what it terms its Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) initiative, which seeks to untangle the international web of often conflicting and inconsistent tax codes. The challenge of tax evasion by the wealthy has been magnified by a digital and global economy and the fluid movement of capital between nations, which, as the OECD notes, erodes the fairness of the tax system.

In one of 13 reports released in the fall of 2015, two years after BEPS was launched, the OECD says tax losses arise from a variety of causes. They include:

- aggressive tax planning by some multinational enterprises (MNEs);

- the interaction of domestic tax rules;

- lack of transparency and coordination between tax administrations;

- limited country enforcement resources; and,

- harmful tax practices.

The OECD study found that estimates of the impact of BEPS on developing countries, as a percentage of tax revenues, are higher than in developed countries given developing countries’ greater reliance on corporate income tax (CIT) revenues. It states: “In a globalised economy, governments need to cooperate and refrain from harmful tax practices, to address tax avoidance effectively, and provide a more certain international environment to attract and sustain investment. Failure to achieve such cooperation would reduce the effectiveness of CIT as a tool for resource mobilisation, which would have a disproportionately harmful impact on developing countries.”4

In today`s hyper-connected global economy, no one should underestimate the complexity of trying to address the challenge of tax avoidance. As is always the case in attempting to deal with international issues, it is in the DNA of nation states to act in their own self-interest. Trying to identify a collective interest in that kind of environment often defies remedy.

But in this case, for Canada it’s not difficult to identify national self-interest in fiscal, economic and political terms. Addressing tax avoidance abuse where it is done either illegally, without transparency or through aggressive tax planning that purposefully distorts the intent of the tax system will have multiple benefits.

Fiscally, if done properly, it will mean a fairer tax system, not more revenue for governments. Limiting tax avoidance for the wealthy needs to be coupled with tax cuts for others. Specifically, that means reducing tax rates for middle and lower-income Canadians by an equal amount. In other words, it should be revenue neutral. For many who believe taxes are already too high and government occupies too large a share of the economy, that will not be seen as a virtue. But even those who share that perspective cannot ignore the fairness issue, where wealthy people can game the system to avoid paying more taxes, while average income earners carry their full load.

In economic terms, a better coordinated domestic and international tax environment should lead to more productive allocation of global resources. Often, in the quest to avoid tax, corporations and individuals simply park their capital to earn interest tax free. What’s required is an international tax framework that ensures profits are taxed where economic activity and value creation occurs. Aligned with that need to be properly designed tax treaties. Their objective must be to protect against double taxation when profits are patriated to the originating nation after taxes of a relatively comparable level have been paid in the host nation.

The political benefits are obvious, and arguably the most important. They relate to the whole notion of the social contract, upon which the legitimacy of government and individuals` willingness to pay their taxes is based. If people see the tax system as inequitable, where the wealthy can take advantage of the system for further personal or corporate enrichment specifically because of their wealth, while others of modest means cannot, the result can lead to growing anger and distrust of governments.

Very few people like paying taxes, but do it because they believe they have an obligation to help support the broader society and economy. They accept -- although it`s not always easy to recognize -- that they receive personal benefits from paying taxes to help support a nation that provides stability, opportunity, a high standard of living, and good quality of life.

But there is also another side to the obligation. The average person will feel obliged to pay taxes, however reluctantly, on the assumption that the tax system is by-and-large fair and treats all people in a way that recognizes their circumstances. Weaken that belief and the political, social and economic consequences can unfold in many unhappy ways.

Notes

1. http://www.edelman.com/insights/intellectual-property/2016-edelman-trust-barometer/

2. http://www.vox.com/2016/4/8/11371712/panama-papers-tax-haven-zucman

3. American Prospect, The Shame of Tax Havens, February 2016

4. p. 4, OEDC-G20 Base Erosion Profit Shifting Project, Explanatory Statement, November 2015

Dale Eisler

Dale Eisler has an extensive background in the federal public service and Canadian journalism. After a 25-year career in journalism with Saskatchewan and national publications, Dale spent 15 years in various senior roles with the Government of Canada, most recently as Assistant Deputy Minister for the Energy Security Task Force at Natural Resources Canada. Prior to that he spent four years serving as Canada’s Consul General in Denver, CO . Before his posting in the U.S., Dale was Assistant Secretary to the federal cabinet for Communications in the Privy Council Office and began his role in Ottawa as Assistant Deputy Minister for Communications in the Finance Department. He received the 2013 Joan Atkinson Federal Public Service Award of Excellence. He is the author of three book, including “False Expectations, Politics and the Pursuit of the Saskatchewan Myth” and, most recently in 2010, the historical fiction novel “Anton, a young boy, his friend and the Russian Revolution.”

People who are passionate about public policy know that the Province of Saskatchewan has pioneered some of Canada’s major policy innovations. The two distinguished public servants after whom the school is named, Albert W. Johnson and Thomas K. Shoyama, used their practical and theoretical knowledge to challenge existing policies and practices, as well as to explore new policies and organizational forms. Earning the label, “the Greatest Generation,” they and their colleagues became part of a group of modernizers who saw government as a positive catalyst of change in post-war Canada. They created a legacy of achievement in public administration and professionalism in public service that remains a continuing inspiration for public servants in Saskatchewan and across the country. The Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy is proud to carry on the tradition by educating students interested in and devoted to advancing public value.