The Post-Pandemic Economy: What do Canadians Want?

This issue of JSGS Policy Brief is part of a series dedicated to exploring and providing evidence-based analysis, policy ideas, recommendations and research conclusions on the various dimensions of the pandemic, as it relates here in Canada and internationally.

By Michael Atkinson, Professor Emeritus, Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy; and Haizhen Mou, Professor, Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public PolicyIn a democracy, governments are expected to decide matters of policy by taking into account the opinions of equally empowered citizens. According to political scientists, this requirement is most easily satisfied when decision-makers track the preferences of the median voter. This fictitious person represents the closest approximation available to the most favoured position on a single-issue dimension.

Lots of things can go wrong. Sometimes the electorate is polarized, showing both intense support for, or intense rejection of, a given policy. In that case knowing the median position is not of much help. Sometimes messages from voters to politicians are distorted by special pleading or unequal representation. Or voters may not have a message to send. Some issues, especially those that involve economic decisions, are so complex and contingent that many electors are unable to form an opinion, leaving politicians with some unpleasant options: guess what citizens might prefer, listen only to those who do have opinions, or try to persuade the median voter to affirm a strategy already worked out.

The situation becomes more difficult when choices are made under crisis conditions. It is safe to say that the median voter in Canada wanted income support programs to get the country through the pandemic induced recession. But now what? Do we “build back better” as some would have it, investing in a social equity and climate change agenda, or do we double down on strategies aimed at restoring a healthy climate for business investment. And is that really a choice anymore? Where is the median voter when we need them?

To help us discover what the median position might look like, in January 2021 we asked a random sample of Canadians their opinion on three key economic questions: What should Canada’s economic priorities be going forward? What should be our budgetary priorities—which areas deserve more investment, which are less important? And, how should we come to terms with the debt? Our 563 respondents resemble the population in the 2016 Canadian Census in terms of age, gender, province of residence, urban/rural area and income groups, with a margin of error of +/- 4.13% (19 times out of 20).

NOTE: Although our initial findings from the survey are captured in this Policy Brief, further analysis is being conducted on the raw data. If you are interested in the actual survey or want to view the questions asked, please click here for more information.

Policy Priorities

We first asked respondents to rank, in order of importance, the following five policy priorities, as we recover from the pandemic:

- Protecting the income of citizens;

- Controlling increases in the cost of goods and services;

- Reducing the level of government debt;

- Reducing income inequalities; and,

- Creating jobs.

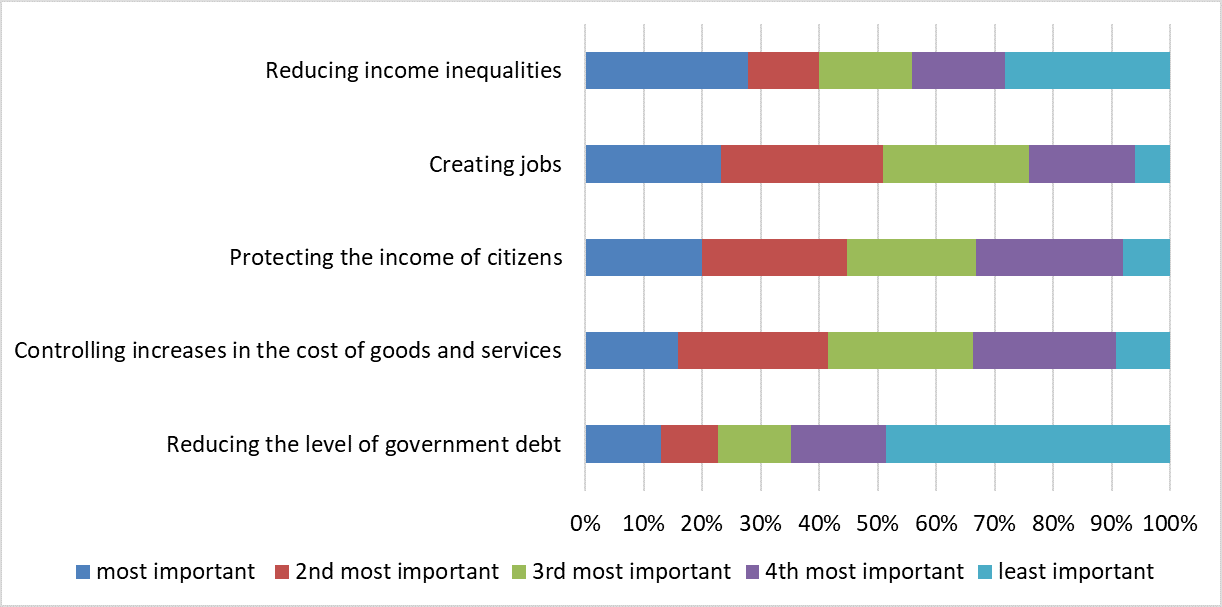

There are no “bad” choices in this list. And while there are other economic priorities that could be included, these represent most of the items that appear on the wish list of pundits, columnists and twitter enthusiasts. Figure 1 summarizes the views of all 563 respondents. The five policy priorities are organized in declining order of importance, beginning with the one judged “most important” by the largest percentage of respondents.

Figure 1: The Most Important Economic Priorities

The traditional macro-economic sweet spot is a combination of high employment, such that the economy is performing at full capacity, and low, stable price inflation. It is highly likely that Canadians want their government to accomplish just this trick. Figure 1 reveals that about 50% of our respondents think that “creating jobs” should be either the first or second economic priority as we emerge from the pandemic. Fewer, but more than 40%, think that controlling inflation (“controlling increases in the cost of goods and service”) should be the first or second priority. Very few, less than 10%, see employment and inflation as the “least important” priorities.

As central as these traditional goals have been, and still are, more of our respondents chose “reducing income inequalities” as their first priority than any other option. The growing sensitivity to income disparities reflects the recent work of economists such as Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, who show that income and wealth disparities have grown since the 1970s. The future is hard to predict, of course, but most people alive today have seen only increases in these disparities and a stagnation of middle class incomes.

Notice, however, that while addressing income disparities is the most important priority for a plurality of our respondents, almost exactly the same proportion make income disparities their least important priority. In short, there is significant division on the importance of addressing economic inequalities: It is very important for some, and not very important for others. That division is not a function of income. In fact, those in the highest income category, those earning more than $100K, were more likely to favour reducing income inequalities. For 20% of our sample, “protecting the income of citizens” is the number one priority, but that choice may speak to the persistent need for temporary relief rather than a hankering for permanent change.

It will likely come as a disappointment to fiscal hawks to learn that very few respondents to this survey think that dealing with the debt is a priority. Almost 50% consider “reducing the level of government debt” the least important of the choices they were offered. It is worth mentioning that men were much more likely than women (17% versus 8%) to favour attention to the deficit, while women had a stronger preference for reducing income inequalities (31% versus 24%). We return to the issue below, but first let’s consider what kinds of spending are most important as we go forward.

Budget Priorities

Economic priorities are quite general; budget priorities reveal specific investment preferences. To gauge how ordinary Canadians might approach the question of budget priorities, we provided our respondents with a number of possible priority areas and asked them to identify the three areas they deemed most deserving of support and the three areas least deserving of support. We pointed out that there are no wrong answers: All of the areas listed have been described by at least some observers as worthy of additional investment.

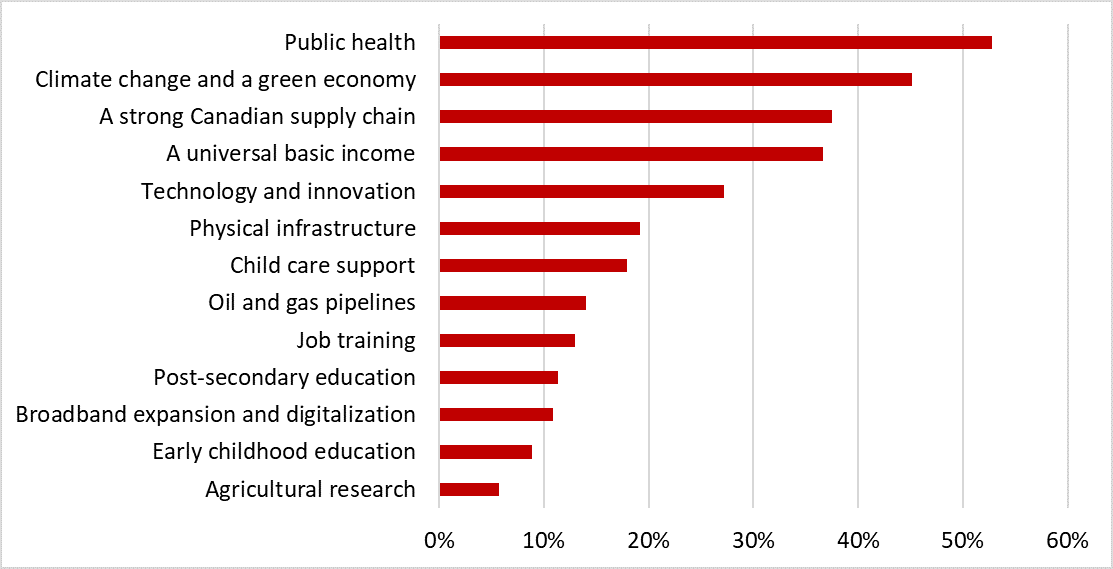

Figure 2: Percentage of Respondents Choosing Each Area as Most Deserving of Support

It comes as no surprise to learn that these Canadians believe public health initiatives deserve high priority. Figure 2 also shows that creating a climate for investment, such as secure supply chains, physical infrastructure, and support for technology and innovation, are among the top six areas most deserving of support. While Canada’s business-oriented think tanks, like the C.D. Howe Institute and the Conference Board of Canada, are skeptical of any additional spending, these priorities are consistent with their preference for shoring up the supply side of the economy.

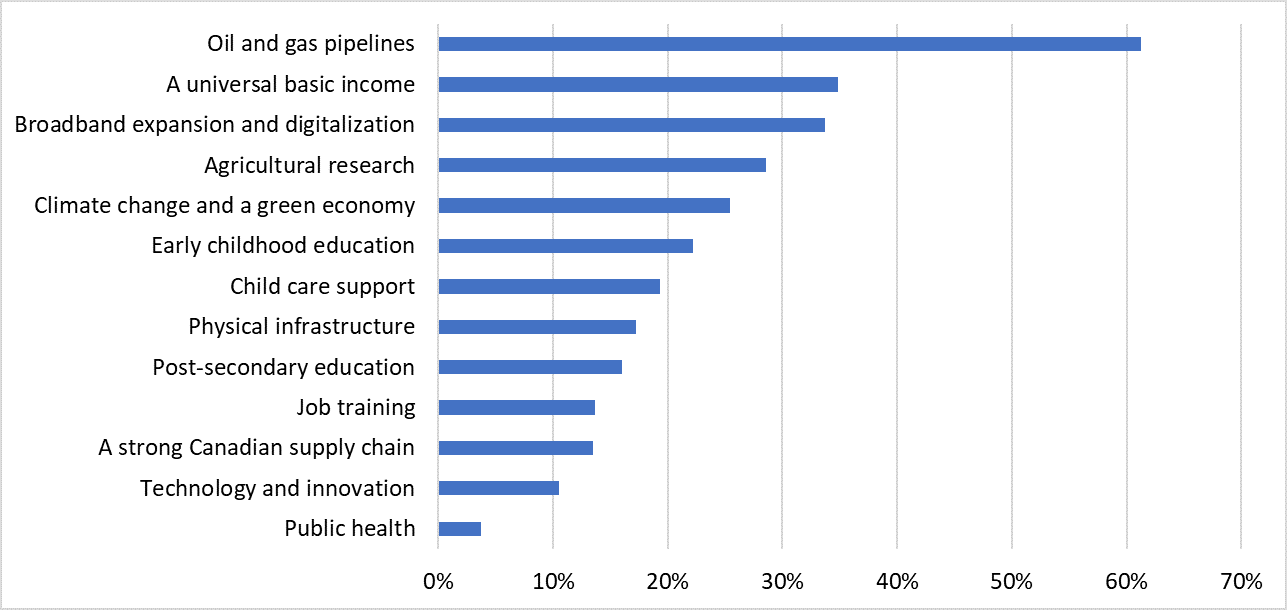

Of more concern from a long-term investment perspective is the relatively low priority accorded to education, whether job training, post-secondary or early childhood. Many economists believe that early childhood education has the potential to significantly improve economic growth, but it ends up second to last among top priorities and, as Figure 3 shows, over 20% of respondents list it among the least important priority areas.

Perhaps the clearest message for our post-pandemic future is to be found in the second most important priority: “climate change and the green economy.” Were it not for the pandemic, it would likely be number one. This preference is shared by respondents from different demographic and regional groups. Given signals contained in the federal government’s Fall Economic Statement, “climate change and a green economy” may be one area in which public priorities and political messaging are converging.

As for the bottom priorities, those deserving the least support, oil and gas pipelines lead the way by a wide margin. Respondents living in Central Canada (Ontario and Québec) were slightly more inclined to label pipelines “least deserving,” but the regional differences are not large. Even Westerners (including respondents from B.C.) show little enthusiasm; over 50% rated pipelines one of the areas least deserving of support. If this choice is the flipside of the green economy preference, the message is quite clear: Canadians are looking toward a post-fossil fuel economy.

Some budget priorities are more perplexing. “A universal basic income” is a good example of a policy preference embraced by a large segment of our respondents and rejected by an almost equally large segment. On this dimension of public policy, the median voter is probably not the story. There are two camps: a left-libertarian argument for more income and expanded personal choice, and a right-social contract argument for targeted assistance and public goods. It will not be easy to find a middle ground.

Figure 3: Percentage of Respondents Choosing Each Area as Least Deserving of Support

Fiscal Discipline?

All of the budget priorities outlined above cost money. Canada’s debt-to-GDP ratio, which combines federal and provincial indebtedness, has grown from 89% in 2019 to about 115% at end of 2020. The federal government’s 2020 Fall Economic Statement included plans for further stimulus spending in the order of $70B to $100B. Even if debts and deficits are not an immediate priority, many academics and practitioners still argue for rules or guidelines to help us avoid a collapse in our credit rating.

Since the 1990s governments in Canada have adopted a variety of fiscal anchors intended to signal their commitment to fiscal responsibility. Balanced budgets were an early favourite, with most provinces adopting some form of balanced budget legislation by 2008. Since then, balanced budgets have fallen out of favour and other targets have been proposed, including debt/GDP ratios and legislated limits on specific spending programs.

We asked our respondents about these fiscal anchors, but we also included measures of economic sustainability that take us beyond fiscal discipline, namely attention to employment levels and to inflation rates. These latter measures speak to the health of the economy rather than the health of government balance sheets, and Canadians in our sample were much more inclined to choose these indicators as the most appropriate. No macro-economist will quarrel with these preferences—they represent the twin preoccupations of macro-economics since at least WWI—but they are seldom used as ways of tracking government budgeting practices and they don’t speak directly to debts and deficits.

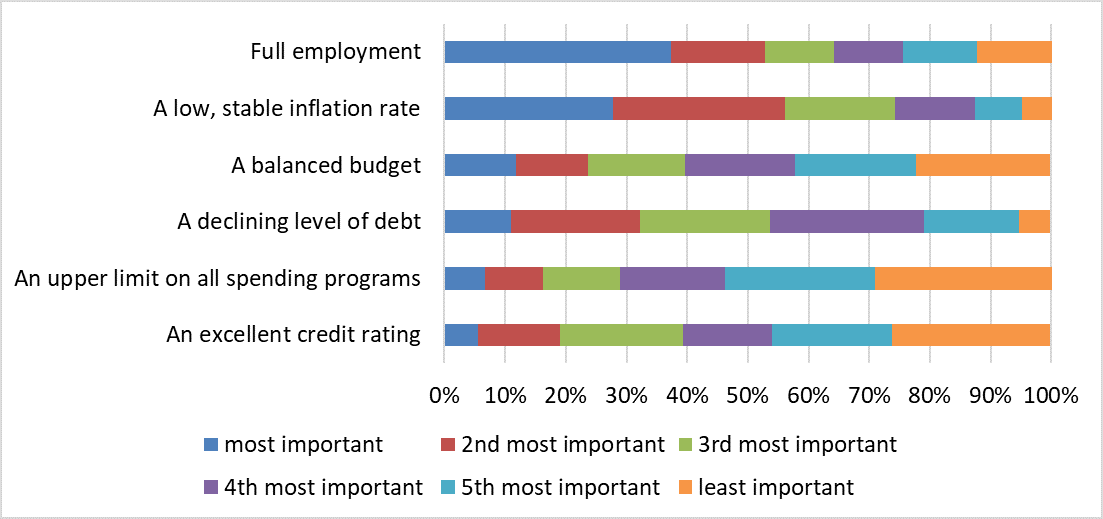

Figure 4: The Most Important Fiscal Anchors

The four conventional budget discipline goals we offered our respondents were much less popular. Of these, a declining level of debt was the first or second choice of about a third of our sample, while a balanced budget was the most, or the second most, important goal for less than a quarter. Very few were interested in capping spending programs or boosting credit ratings.

It’s not that Canadians are in denial about the unprecedented scale of pandemic associated commitments. We asked our respondents to agree or disagree with the following statement; “The federal government’s debt level after COVID-19 is a more serious problem than most people recognize.” Over 60% agreed or strongly agreed with the statement. The debt level is a problem for our respondents, but their focus is elsewhere, namely on the economy as a whole. In this they appear to be in step with the federal government, which announced that the timing for an unwinding of its income support programs would depend on employment rates rather than deficit levels.

If Canadians are not currently obsessing about the debt, it may not be a signal that conventional public finance concerns are passé. We asked about priorities, and priorities can change. Much depends on whether the pandemic becomes a moment for reflection on how the economic stewardship of governments, and other institutions, should be evaluated. If the performance of the economy as a whole remains the principal reference point, and not just government’s budgetary prospects, then expect governments to avoid conspicuous commitments to fiscal discipline.

This type of attitude is bound to be worrisome for deficit hawks and (at least some) orthodox economists. It may comport with the preferences of a majority of voters, but it may also be bad public policy. If the economy as a whole is going to be our North Star in matters of debt, then estimating what the economy requires will be crucial. That means estimating the size of the current output gap, the difference between what the economy currently produces and what could be achieved if existing capital, labour and technology were fully employed.

Closing the output gap is a legitimate ambition, and arguably should trump deficit worries, especially when interest rates are low. But if closing the gap means increasing inflation, then Canadians will object that their preferred priorities—full employment and low inflation—are not being met. At that point expect a shift to prioritizing the deficit.

Conclusion

Governing by polls has a bad name, one that is to some degree deserved. But if governments just ignore their constituents, then it is hard to argue that policy outcomes are even the indirect product of democratic choices. At the very least, politicians need to be aware of citizen preferences. The results we have reported here suggest three candidates for heightened awareness.

First, the economy as a whole, and traditional macro-economic criteria, are top of mind for Canadians at the moment. It doesn’t matter that several of Canada’s economic think tanks have a different agenda. The Conference Board, for example, urges policy-makers to meet the post-COVID era by “first stabilizing and then reducing the aggregate public debt-to-GDP ratio to enable the country to get through the next crisis or recession when it comes.” Canadians are not there yet, and any move toward austerity, beyond unwinding the pandemic spending programs themselves, will be met with a cold shoulder.

Second, budget choices will reveal tensions. The term “build back better” has become a political soundbite that could refer to just about any combination of priorities. Our research suggests that enthusiasts should exercise some caution in reading too much into the slogan. Some areas—a green economy and a more robust public health regime—will generate a broadly positive response, but others, such as “a universal basic income,” are likely to produce division. Those hoping for long-term investments in post-secondary education, training and early childhood education, face a particularly steep climb. These areas are major supply side investments, but Canadians will need some convincing that they should be budget priorities.

Finally, many of our respondents are concerned about growing economic disparities. The pandemic has drawn to their attention profound weaknesses in parts of the health care system, weaknesses that correlate strongly with economic and political power. Outbursts of populism add urgency to the mix. Aside from the ethical case for redistribution, many Canadians will be supportive if only for prudential reasons. Others believe that a broadly based economic recovery will be enough to correct these imbalances. The track record on that front is not encouraging, and if our research is any indication, Canadians seem to know that.

ISSN 2369-0224 (Print) ISSN 2369-0232 (Online)

Michael Atkinson

Michael Atkinson is a Professor Emeritus in the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy (JSGS) and Adjunct Professor at the University of Victoria. He has held a number of academic administrative appointments including Provost and Vice President Academic at the University of Saskatchewan (1997-2007) and JSGS Executive Director (2008-2015). His academic background is in political science and he has published extensively in that field and in public administration and public policy.

Haizhen Mou

Haizhen Mou is a Professor in the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy. Her primary research interests include fiscal governance, government budget management, fiscal federalism, and health care financing and expenditure, often from a political economy perspective. She received two SSHRC grants and several other awards.