The state of provincial social assistance in Canada

In Canada, as in other advanced industrial societies, social assistance is a central component of the welfare state. This is true because social assistance, which refers to a set of need-based, last-resort income programs, is the “last safety net” in that it supports members of some of the most vulnerable populations in our society. Commonly referred to as welfare, social assistance does not have a good reputation in Canada. In fact, just like in the United States, the term welfare frequently has negative connotations, in both popular parlance and media discourse.

By Daniel Béland, Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy, and Pierre-Marc Daigneault, Department of Political Science, Université LavalIn Canada, as in other advanced industrial societies, social assistance is a central component of the welfare state. This is true because social assistance, which refers to a set of need-based, last-resort income programs, is the “last safety net” in that it supports members of some of the most vulnerable populations in our society. Commonly referred to as welfare, social assistance does not have a good reputation in Canada1. In fact, just like in the United States, the term welfare frequently has negative connotations, in both popular parlance and media discourse.

Criticism of social assistance

Harsh criticisms directed at social assistance have indeed proved widespread since the 1980s, especially within conservative and neoliberal circles. These critics have typically stressed the need to promote personal responsibility and fight a “culture of dependency” grounded in an alleged lack of work ethics. Many criticisms are premised on the traditional distinction between deserving and undeserving poor, which can be traced back to the debate over the English Poor Laws. This distinction remains the implicit ideological background of many welfare debates, in Canada and in other advanced industrial countries.

Other critics of social assistance have promoted the activation of clients, through a tightening of the relationship between social assistance and the labour market. Their basic claim is that Western societies have gone too far in granting rights and entitlements to citizens. In this context, the argument is to limit such rights, or at least balance them with new responsibilities on the part of social assistance beneficiaries, who should undertake training or agree to work in order to keep receiving their benefits.

A related yet different line of criticism holds that welfare reform should become a central element of a larger human capital development strategy. This perspective overlaps with activation when the aim of human capital development is to improve the skills of welfare beneficiaries in order to increase their capacity to pursue full-time work and economic productivity. From this perspective, critics claim, social assistance can become a tool of economic development. More generally, welfare reform is described as a “social investment” that, if done properly, can help reduce the scope and cost for the public purse of social problems such as crime, educational underachievement, health problems, and poverty, including child poverty.

Considering these perspectives and enduring fiscal pressures that push governments to control costs, across the advanced industrial world social assistance has significantly changed in recent decades. This is the case in Canada, a country where, with the key exception of Indigenous peoples living on reserve,2 social assistance for working-aged people is a provincial matter. Although citizens and policymakers might think that they know a lot about welfare, in reality, public knowledge about provincial social assistance programs is rather sketchy. As a result, much more work is needed to provide a truly comparative and systematic overview of major issues and trends in this policy area, which is the safety net of last resort for so many Canadians. Moreover, because each province operates its own social assistance program, a great deal can be learned by analyzing and comparing the different jurisdictions in a rigorous manner.

A systemic look at social assistance across Canada

This is exactly what our recent University of Toronto Press volume does. Titled Welfare Reform in Canada: Provincial Social Assistance in Comparative Perspective, this volume gathers some of the best specialists of social assistance in Canada, from both within and outside academia. Contributors include scholars from different disciplines (political science, economics, sociology and social work) as well as current and former policy practitioners. They

offer the first systematic look at provincial social assistance in more than 15 years. A significant feature of the volume is that each province gets its own chapter, which allows for an in-depth, comparative look at social assistance trends and reforms across the country. Simultaneously, broad historical, international, empirical contributions allow the reader to grasp the “big picture” of social assistance while paying attention to its various dimensions and issues. Finally, more focused chapters explore crucial subjects such as Indigenous issues, activation programs, disability, gender, housing and homelessness, immigration, and population aging. The result is a rigorous analysis of social assistance trends in Canada that both practitioners and researchers should find useful as the most comprehensive primer on social assistance ever published.

Several of our volume’s findings are particularly striking. First, as Ronald Kneebone and Katherine White show in their contribution, as in the past, provincial social assistance benefits for single employable individuals are set well below what is needed to cover their most basic economic needs, except for Newfoundland and Labrador. Even in this case, however, the benefits are compared to Christopher Sarlo’s measure of basic needs, which is significantly lower than commonly used low income indicators such as the market basket measure (MBM). On average, because provincial governments provide extra support for children, lone parents as well as married parents fare relatively better, although this is much more the case in Prince Edward Island, Québec and Saskatchewan than in British Columbia, Manitoba and Nova Scotia.

Second, as this example suggests, significant variations among provinces persist in the field of provincial social assistance. At least regarding differences in benefit levels for single employables, lone parents, and married parents, there is no evidence of a strong convergence. In his chapter, Gerard Boychuk makes a similar argument to the effect that there is no clear convergence in benefits adequacy.

Third, and simultaneously, there are clear signs of convergence in the field of disability benefits, which, since the 1990s, have declined in all provinces except Québec. Yet, in a number of provinces, such as Alberta, there is an obvious gap between those with temporary and permanent disabilities, as the latter group sometimes receives much more generous benefits than the former.

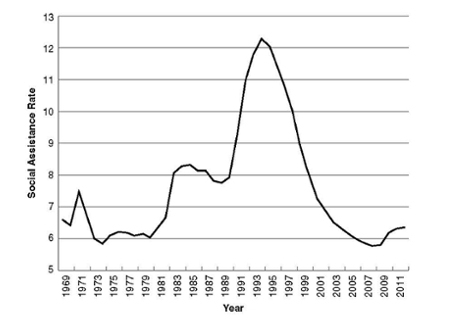

Fourth, since the mid-1990s, the average social assistance recipiency rate has declined across the country. While the recipiency rate was more than 12 per cent in 1995, it is now only slightly more than 6 per cent, which represents a deep change in provincial social assistance. Today in Canada, the average recipiency rate is comparable to what it was 45 years ago, towards the end of the post-war boom. Because Kneebone and White as well as Boychuk show in their respective chapters that the social assistance recipiency rate is highly correlated with the employment rate, there is no doubt that the main driver of this decline is economic. However, they also argue that policy reform must not be neglected as a potential factor behind declining caseloads.

Finally, as Boychuk suggests in his chapter on the historical development of social assistance in Canada, the termination of the federal Canada Assistance Plan (CAP) in the mid-1990s did not result in the strong, unilateral impact on provincial social assistance that many observers anticipated at the time. A reason for this is the fact that CAP itself featured relatively weak conditions imposed on the provinces in exchange for federal funding. Boychuk further argues that social assistance reform is primarily driven by economic and political factors, whose impact can vary greatly from province to province. The policy lesson here is that, to understand social assistance in Canada, one must look at each province, and not at Ottawa. This means the provinces are entirely responsible for the well-being of some of the most vulnerable segments of the Canadian population.

Figure 1: The Social Assistance Rate, Canada, 1969-2012

Issues for further research and analysis

Because our volume is not the final word on the topic, it points to a number of issues future research and policy work on social assistance in Canada should address. First, it identifies a major “data problem” that must urgently be addressed. Several of our contributors lamented how difficult it is to obtain information on basic issues such as who receives assistance in each province. For instance, as Tracy Smith-Carrier and Jenny Mitchell note in their chapter on immigration, data on the status of immigrants within provincial social assistance systems is very hard to obtain. At the broadest level, in order to improve our knowledge of welfare reform, we ask all provincial governments to address such gaps and make more information available on social assistance caseloads and demographics.

Beyond this general data problem, our volume suggests that more case studies and comparative research on provincial social assistance are needed. This is especially true concerning smaller, less-populous provinces such as New Brunswick and Saskatchewan, which are less studied on average than Ontario, Québec and British Columbia. This is an unfortunate situation, as scholars and policymakers can learn equally from all provinces, regardless of their population size.

Finally, more work is needed on particular populations and their relationship to provincial social assistance. In addition to the situation of immigrants mentioned above, the status of Aboriginal peoples within the field of social assistance requires much more research, especially in relationship to the changing and complex interactions among federal and provincial programs dealing respectively with on-reserve and off-reserve populations. Another issue that requires more attention on the part of both scholars and practitioners, is the impact of population aging on welfare rolls.

It must be considered in the context of the 2012 federal decision to increase the eligibility age of Old Age Security (OAS) and the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS) from 65 to 67 years old, between 2023 and 2029. This increase should negatively affect not only the fiscal situation of the provinces, as the long-term unemployed would need to stay on provincial welfare rolls until 67 instead of 65, but also the clients because social assistance benefits are typically less generous than OAS and GIS combined. Overall, more knowledge is needed about the impact of population aging on provincial social assistance in Canada.

Beyond the issue of social assistance, this volume stresses the importance of rigorous case studies and comparative analyses of public policy across the 10 provinces. This case was clearly made in the book co-authored by Michael Atkinson et al., Governance and Public Policy in Canada: A View from the Provinces (University of Toronto Press, 2013). More recently, in a di erent policy area, Greg Marchildon, Livio Di Matteo and their contributors recognize the need for systematic, inter-provincial comparative research in Bending the Cost Curve in Health Care (University of Toronto Press, 2014). We hope that our volume, alongside these two existing books and other recent publications, helps draw more attention to provincial public policy from both a scholarly and a practical standpoint.

Notes

1 Harell, A., Soroka, S., & Mahon, A. (2008). Is welfare a dirty word? Canadian public opinion on social assistance policies. Policy Options - Options politiques, 29(8): 53-56.

2 The federal government pays for on reserve bene ts at the same rate as provincial social assistance in the province where they live.

Daniel Béland

Daniel Béland is a professor and Canada Research Chair in Public Policy (Tier 1) at the Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy (University of Saskatchewan campus). A student of comparative fiscal and social policy, he has published 12 books and more than 100 articles in peer-reviewed journals. Recent books include The Politics of Policy Change: Welfare, Medicare, and Social Security Reform in the United States (Georgetown University Press, 2012; with Alex Waddan), Ideas and Politics in Social Science Research (Oxford University Press, 2011; co-edited with Robert Henry Cox), What is Social Policy? Understanding the Welfare State (Polity, 2010), Public and Private Social Policy: Health and Pension Policies in a New Era (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008; co-edited with Brian Gran), and Nationalism and Social Policy: The Politics of Territorial Solidarity (Oxford University Press, 2008; with André Lecours). You can find more about his work on his website: www.danielbeland.org

Pierre-Marc Daigneault

Pierre-Marc Daigneault is an assistant professor of public policy and public administration in the Department of Political Science at Université Laval. Before his current position, he was a postdoctoral fellow at the École nationale d’administration publique (ÉNAP), the Ministère de l’Emploi et de la Solidarité sociale du Québec and the Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy (University of Saskatchewan campus). Trained as a political scientist, he pursues research on social policy and, in particular, on social assistance and activation programs. In addition, Daigneault has a keen interest in questions related to governance, policy paradigms, program evaluation and research methods. His research has been published as book chapters and in various peer-reviewed journals, such as the American Journal of Evaluation, Canadian Journal of Political Science, Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, Evaluation and Program Planning, Evaluation Review, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, Journal of European Public Policy, Political Studies Review, and the Journal of Mixed Methods Research.

People who are passionate about public policy know that the Province of Saskatchewan has pioneered some of Canada’s major policy innovations. The two distinguished public servants after whom the school is named, Albert W. Johnson and Thomas K. Shoyama, used their practical and theoretical knowledge to challenge existing policies and practices, as well as to explore new policies and organizational forms. Earning the label, “the Greatest Generation,” they and their colleagues became part of a group of modernizers who saw government as a positive catalyst of change in post-war Canada. They created a legacy of achievement in public administration and professionalism in public service that remains a continuing inspiration for public servants in Saskatchewan and across the country. The Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy is proud to carry on the tradition by educating students interested in and devoted to advancing public value.